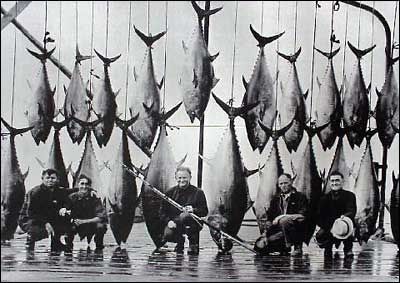

“Once caught never returned” is the motto of the Exotic Fishing Tournament hosted by the Native Fish Conservancy (NFC). Participating anglers are encouraged to keep all the "invasive" fish species they catch. The team with the greatest number of exotics wins the $200.00 grand prize. How the angler opts to use the fish is of no interest to the NFC. The organization's press release reads,

“We encourage everyone to treat exotics with reckless, fishing exuberance. If you catch exotics, aquarium-keep them, grill them, feed them to your pets, turn them into fertilizer. Do anything except return them to their former homes.”Wow.

I believe that the human contribution to the contemporary, epic loss of biodiversity is a sin (of a decidedly secular variety). Fewer species translates into less genetic, dietary and behavioral variety, making it that much more difficult for Nature to adapt in the future.

Nevertheless, when I first read about the Exotic Fishing Tournament, I cast nervous glances at my fellow subway commuters, worried that they might notice the, um, "material" in my hands.

As Timothy Burke (Easily Distracted) writes,

“I do wonder about that attitude a bit, not just in the context of fishing, but as a whole. When I read some of the material on the dangers of invasive species, its rhetoric and tropes sometimes seem uncannily familiar, reminding me very much of ideas about race, miscegenation and nativism in modern colonialism, in post-colonial nationalism, and in identity politics. There’s some similar desire to stop the forward motion of change, to fix environments (human or natural) in their tracks, the same suspicion of dynamism. What is particularly striking to me is that the arguments against 'invasive species' even from scientists sometimes seem not so much technical or scientific (when they are, they usually rest on the relatively weak assertion that there is a burning necessity for general biodiversity that trumps all other possible principles of ecological stewardship) but mostly aesthetic.”Excepting my belief that greater biodiversity does make for a healthier ecosystem, I am in total agreement. Strangely, I do not find it uncomfortable to occupy such an ambivalent position. I argue stridently for both sides of the coin, perfectly content in my hypocrisy. To better explain myself, I turn to the conclusion of an old artist statement.

“My own opinions and arguments are flawed, of course. Nature is not a comprehensible entity; she is indifferent to humanity. Given the burgeoning world population and our reluctance to consider serious action, it is naïve of me to think it possible for humanity to live in a truly sustainable fashion. Simply because an ideal is unattainable, however, one need not abandon it. In fact, acknowledging contradiction can better serve the individual; in a world increasingly consumed by ambivalence and captivated by cleverly marketed distractions, we must accept some degree of contradiction in order to further progress. We can aim for sustainability only if we accept the complexity of the task. In essence, this is the stuff of art – a flawed platform with no up or down, no east or west, on which to build the self and, in turn, shape objects to explain the proposed self. Art reveals the private obsessions of the psyche and better expresses the individual’s inner fragmentation, a consequence of the ideal being at odds with the real.”As the quote suggests, the flawed platform is as applicable to conservation as it is to art making. Some degree of relativism is necessary when considering invasive species. For example, zebra mussels (Dreissena polymorph) and European carp (Cyprinus carpio) are greater threats to biodiversity than multiflora rose (Rosa multiflora). All three are exotic/invasive species, but we need not raise an uproar about the latter species.

I hope many of the anglers participating in the Exotic Fishing Tournament treat their quarry with respect. Throwing away or otherwise mistreating fish of any species is wrong but, given the nature of this affair, the celebrated waste would be that much more unsettling.

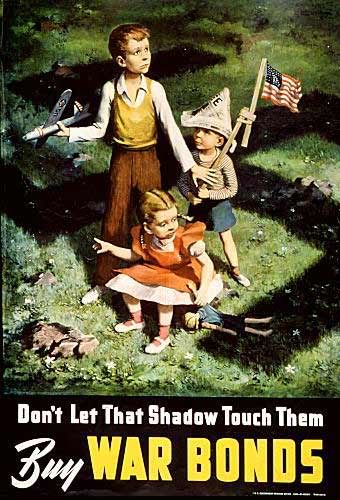

Photo credit: WorldWar2History.info