Alessandra Sanguinetti

"Untitled, from On the Sixth Day"

1996–2004

Fujiflex Print

Courtesy Yossi Milo Gallery

I first visited Alessandra Sanguinetti's exhibition, "On the Sixth Day," currently on display at Yossi Milo Gallery in Chelsea, with my parents. My father was drawn to a photograph of three dogs running a boar. Obscured by a foreground tree, the boar's expression remains unseen; the heavy-bodied beast has turned to face his pursuers and the body language of the dogs, tensed in excited ambivalence, communicates the moment's urgency. Recalling his own boar hunting experiences, my father said, "You should see how they castrate these boars down in Florida. The sheer power of the animal and the big Florida boys who flip them, tie off the testicles and cut through them with a knife...all in one clean movement. It's dramatic, let me tell you." This, I imagine, was not the typical commentary of most gallery visitors.

Alessandra Sanguinetti

"Untitled, from On the Sixth Day"

1996–2004

Fujiflex Print

Courtesy Yossi Milo Gallery

I sometimes describe my rural upbringing as a blood baptism. Fanciful as this may seem, it is, to a degree, accurate. As I told an interviewer for Scrawled, a short-lived arts and culture webzine,

"I was introduced to nature's ambivalence through my own doings in the rural South...Some of my early memories are, quite literally, bloody. To this day, I find blood-soaked hands on a cold winter morning profoundly beautiful...the neon red glowing on my trembling hands was spilt life...an introduction to "the Circle of Life," even if it wasn't at all what Disney force-fed us...passing through one extreme brings you out at the other."

These bloody lessons are central to Sanguinetti's showing. Most of the photographs she includes are stunning meditations on the reciprocal relationship of life and death. The subjects central to Sanguinetti's compositions are not those creatures God fashioned to "rule over the fish of the sea and the birds of the air, over the livestock, over all the earth, and over all the creatures that move along the ground."(1) Instead, she focuses on the subjugated parties, both the domesticated - cats, dogs, lambs, horses, pigs, cows and chickens - and wild - rabbits, boars and an unidentified rodent resembling a guinea pig - residents of eastern Argentina. Despite the fact that very few people appear in the photographs, their considerable presence - their dominion, if you will - is felt throughout "On the Sixth Day."

Alessandra Sanguinetti

"Untitled, from On the Sixth Day"

1996–2004

Fujiflex Print

Courtesy Yossi Milo Gallery

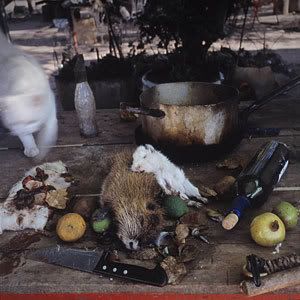

At times, Sanguinetti's photographs seem over-determined, or orchestrated. Two wild rodents lay dead on a table, surrounded by various fruits, a carving knife and a bottle of wine. An iron pot sits just behind this array and a white cat enters the frame from the left to investigate. Only the cat's entrance seems natural; the dead game, the abundant fruit and the wine all seem didactic, intent on reminding viewers that our meals, even those enjoyed over a bottle of wine and high-minded conversation, are born of killing and butchering. The message - the blood of these animals represents a livelihood, sustenance - is here blunt and crude, even if the photograph itself is no less striking, no less sensuous, for it.

The artist writes, "To portray an animal is to name it. Once named it acquires a new life, and then, is spared death." I am sympathetic to Sanguinetti's appreciation of the animal entity. To view another species as equally worthy of reverence or, more valuable still, to identify with it - to imaginatively merge yourself with another being - is to open yourself to a transcendental experience. In this sense, death is spared, via a broken connection to the corporeal and the conscious, however fleeting this reprieve may be. Importantly, this transcendence is rooted in a reduction or erasure of the individual actors, both the human and the "lower" animal, over which man has dominion, according to the sixth day of Genesis. Essentially, then, the transfiguration is achieved via an explicit denial of the Biblical narrative, by rejection of dominion and of the scalae naturae.

Sanguinetti also writes, "It is possible that by exploring the fine line that separates us from what we rule, we may reach a better understanding of our own nature." Indeed, although I believe we need to dismiss "the fine line" altogether, or at least blur it beyond recognition. Judging by the reaction of some exhibition viewers, Sanguinetti succeeds in doing just that. Bill Gusky, a thoughtful artist and writer, seems almost appalled by the exhibition. He describes reacting to the "wretched horror of animate physical being."

"It's something I don't want to think about as I carve into a roast chicken or a pair of fried eggs. It's something I can only be driven to contemplate. And in contemplating it I almost feel like I'm paying a bill, performing some sort of gut-wrenching penance for my carnivorous sins. It's the kind of penance that brings no redemption, whose chief service seems to be to make you question your own existence, even the parts that only death itself can change."

No redemption? Every time I eat meat - rarely, as I only eat animals that I have killed or caught myself - I am consumed by such contemplation. I think about energy and death when I eat soy and vegetables, as the harvesting and transportation of these foods has a moral price tag, too. Even those people lucky enough to live solely on the foods they tend themselves should consider the death and recycling - again, the circle of life - that all such processes entail.

The food chain is not the only window to genuflection, however. Our bodies are covered with a zoo of miniature species fighting for survival. We share our beds with pseudoscorpions and countless mites, each night crawling and hunting over our mattresses and through the forests of our body hair. Focusing on the often unpleasant realities of putting food on the table or on dramatic shifts in scale - whether micro (the mite level and smaller) or macro (the expansive, breathing universe) - is, for me, redemptive or, at least, transcendental in the manner described above. If I go through a day without questioning my existence, then I have not lived that day.

Alessandra Sanguinetti

"Untitled, from On the Sixth Day"

1996–2004

Fujiflex Print

Courtesy Yossi Milo Gallery

I do not intend to belittle Gusky's perspective. I've lived away from my rural roots for some time now, and I imagine it will be at least another decade, maybe more, before I return to the woods. I appreciate urban living and, truth be told, I appreciate rural living that much more for it. The distance granted by my time in New York City has allowed me to more fully understand the evolution of our relationship to other species. The rural perspective is vanishing, and the intimate, often messy relationship between rural folks and their animal brethren is being replaced (and bastardized) by the industrial sector, dealing death on a massive scale, ignorant of moral consideration.

Alessandra Sanguinetti

"Untitled, from On the Sixth Day"

1996–2004

Fujiflex Print

Courtesy Yossi Milo Gallery

But Gusky's review of "On the Sixth Day" does worry me, principally because of his suggestion that children be left outside the gallery, "unless you'd like some day to be part of a Menendez murder re-enactment." Sanguinetti's photographs are often distressing, to be sure, but there is much value in coming to terms with corporeal truths at an early age. Admiring the picture of a drying skin, hung between two trees, I am reminded of the exhilaration and disgust, experienced concurrently, I felt as I skinned my first animal or gutted my first duck. Those complicated experiences stay with me, even after years of repetition, and I see no connection between them and violent desire.

Quite the opposite, in fact. I am unable to watch contemporary shock films, like "Hostel" or "Saw." I can not abide their sadism and I'm horrified that torture is turned into spectacle, even though it's of the ketchup-and-rubber-knife variety. On the other hand, those friends of mine most distanced from their food sources, in awareness or geography, eagerly await the next torture "topper," and expect to be titillated and entertained. I'm not suggesting every child be asked to kill, butcher and consume an animal - that's a reprehensible proposal - but I do believe Sanguinetti's photographs are as valuable to children as they are to adults.

I visited the exhibition a second time this past week. Alone with the photographs, I felt something I can only describe as redemption through connection. As an atheist, I'm hesitant to dub anything "a religious experience," but I wrestled with an ambivalent meeting of joy and pathos, a powerful, unsettling union. The grey territory I found myself navigating is that blurred, smudged and partially erased "fine line" Sanguinetti describes. Had she been present in the gallery, I might have embraced her.

Given the subject matter of the photographs included in "On the Sixth Day," it's all too easy for someone with my interests to fall into a rabbit hole of moralizing and hand wringing. This review, then, is really more of a reaction; it's a temporary exorcism, a cold shower for the mind, I suppose. But I feel I should end by stressing the aesthetic success of Sanguinetti's pictures. Her technical and compositional choices - particularly in regards to focus and perspective - come together marvelously, and that's exactly what I do: I marvel at their poignancy and their beauty.

Alessandra Sanguinetti

"Untitled, from On the Sixth Day"

1996–2004

Fujiflex Print

Courtesy Yossi Milo Gallery

(1) New International Version of The Holy Bible, International Bible Society, 1984

Photo credits: All images: Alessandra Sanguinetti, Courtesy Yossi Milo Gallery

4 comments:

The Menendez reaction was fairly hyperbolic, probably a weak stab at humor as well, as was the reference to the au pair. The horror Sanguinetti shows is part of life, and many parents want to expose their kids to life's harsh realities in protected ways. This might be a good venue for that.

But guaranteed, some kids will be really upset by some of the images. Is this a positive thing? Well, maybe, or maybe it's kind of cruel to take certain kids in that far over their emotional heads. Regardless, I'd still stand by the suggestion that the images are somewhat upsetting, even if my take in the blog went a little overboard.

Bill:

I have little doubt that you're right; some of the images will prove disturbng for viewers, young and old alike. However, in these difficult times a familiarity with death and "life's harsh realities" is that much more vital.

I'm biased, admittedly, as I wrestled with the emotional flux and shock of butchering at a young age myself, and I feel this intimacy with innards is responsible for a deep-rooted morality and empathy. Treat your neighbor as yourself just doesn't teach interconnectivity in the same way.

Unfortunately, my writing about these issues reads like so much self-aggrandizing navel gazing. I'd much rather it didn't....I just don't know how to deal with these issues without relating personal experience.

Anyway, thanks for responding.

As a child I would have found the images traumatizing and not much help in recognizing life's harsh realities. It most likely would have produced nightmares for me and sleepless nights for my mother. I came to be quite accepting of life's realities - to the point where I could help butcher freshly slaughtered animals, but it wasn't until my late teens.

On a different note, the unidentified rodents are most likely a capybara (or possibly a nutria) and a viscachas which are in the chinchilla family.

Deborah:

I'm beginning to think I'm just too much of a kid myself to be a good judge of what might disturb children. I'm more of the fun uncle/godfather type, the one who participates in the kids' fantasy worlds, which thrills them...until my monster performance proves a little too convincing and, then, tears and screams aplenty.

That's not much fun for anybody, especially the parents, so perhaps I was too quick to criticize Bill's parental warning. It's probably a good thing I don't plan to have any of my own. That said, I do think many children would not respond negatively, and I suspect that those who grow up in a rural area will have less qualms with this particular subject matter.

More importantly, though, thanks for the species IDs. The larger rodent doesn't look quite like a capybara (Hydrochoerus hydrochaeris) and, upon further review, I think the snout/nose is wrong. The nutria (Myocastor coyprus) or coypu, though, seems likely (and the snout fits). I mistakingly believed this species to be a northern South American species when, in fact, it is native to Argentina and Chile. It has spread since then, unfortunately, and is now considered one of the more destructive invasive species in the southern United States, as it takes a toll on wetland stability...like a muskrat on 'roids. In an interesting twist, the nutria established in Florida and the Gulf Coast may provide sustenance for the "alien" pythons taking up residence there.

Post a Comment