Michael Light

"Bellman's Creek Marsh in the Meadowlands, I-95 and Hackensack River Beyond, NJ, 2007"

2007

Pigment print on aluminum

24 x 30 inches (or 40 x 50 inches)

-Lewis Lapham, Harper's Magazine (November 2000)

When an airline representative asks if I would prefer an aisle or window seat, I opt for the view. Cramped legs and bathroom trip niceties are a small price to pay. Peering through the reinforced panes as a young boy, I was afforded the perspective required to imaginatively connect a black-and-white aerial survey of my parents’ farm to my ground-level experience of those woods, fields, and marshes. I could at last identify the contours of a pond or stand of trees that I had explored on foot many times. This recognized correspondence thrilled me. A decade on, as a teenage pilot-in-training, I was too enamored of the panorama to mind the specifics of stall recovery procedure, and today all I really recall of the hours logged at the yoke is the exuberant joy I felt looking down on the thin peninsula of farmland separating the Chesapeake Bay from the Atlantic Ocean.

From above, we comprehend land as a cartographer; our mundane conceptions of scale and place are expanded. Michael Light's handsome, handmade Bookworks, on display at Hosfelt Gallery, celebrate this perspectival shift. The artist's books are comprised of aerial photographs shot "with a large-format camera from small, self-piloted aircraft and rented helicopters," each book a document of regional topography, settlement or industrialization. Many photographers aim to "[investigate] the complex landscapes of America," but the aerial aspect of Light's approach elevates his pictures; the images do provide an archaeological record of our culture's contemporary landscape, but the perspective - looking down or across the Earth's flesh from on high - nods to universal and geologic time.

Michael Light

"Deep Springs Valley at 500', 1600 hours, Big Pine, CA

2000

Pigment print on aluminum

24 x 30 inches (or 40 x 50 inches)

The artist states that he is seeking "certain sublimities and timelessnesses and continuities amidst what might commonly otherwise be considered 'wastescapes' or 'nonscapes'" and this search has resulted in the six photographic surveys on display at Hosfelt: "New York Harbor, 03.29.07"; "Rancho San Pedro, 04.28.06"; "Los Angeles, 02.12.04"; "Bingham Mine/Garfield Stack, 04.21.06"; "Some Dry Space, 2003"; "Los Angeles, 07.27.05". His bookworks encourage us to question conventional notions of natural and artificial, and also to consider these environments with respect to the full sweep of time and scale.

"New York Harbor, 03.29.07" is of particular interest to me, and not only because I currently call New York City home. Figuring prominently in this collection is the vast marsh of phragmites, roadways, spartina, telephone poles, landfills, radio towers, and cargo trailers known as the Meadowlands. This is complex terrain, literally and metaphorically. The Meadowlands possess a torn grandeur unrivaled even by the "virgin Nature" we revere in literature and film, on postcards and calendars. Without having traveled to the Grand Canyon, most people have an idea of what they would (or should) "feel" there. They have already experienced it on television.(1) Virgin Nature is neatly labelled and classified, packaged, marketed, and sold. The mess of the Meadowlands, by contrast, resists classification. It reminds us that real Nature - the evolving, ambivalent, often brutal Nature - includes man. Artist and writer John R. Quinn describes the Meadowlands in his book, Fields of Sun and Grass.

"Whether or not the meadows fill any sort of primal need for nature in the eyes of travelers who view them from the Turnpike, wilderness these broad, grassy plains surely are. For though defiled nearly to the utmost, they are yet filled with life - a complex, living biomass that has simply made the best of the industrial juggernaut that has all but overwhelmed it. The meadows have adapted, and endured. And in their own unique way they possess a living beauty that has not been obliterated."

Michael Light

"Bellman's Creek Marsh Looking North, I-95 and Overpeck Creek at Left, Ridgefield, NJ, 2007"

2007

Pigment print on aluminum

24 x 30 inches (or 40 x 50 inches)

Robert Smithson, another artist who, like Quinn, spent his childhood in northern New Jersey and much of his adult life in New York City, wrote, "Even the most advanced tools and machines are made of the raw matter of the earth." Smithson’s statement comes to mind as we speed along the New Jersey Turnpike, passing the industrial detritus that rises up from the reeds or settles into the mud. The tired metal towers, the cinder blocks, the coke bottles, and the discarded tires, the intricate refinery pipeworks, the fat garbage bags, the used condoms, the plastic milk cartons, and the rusty trunks -–all of these things may not be separated from the phragmites, the egret, the turtle, the otter, and the tern. Our existence is woven into past and present, as are the products of our being, a weave which may be dissected only by arrogance or ignorance. To dismiss the Meadowlands as a wasted landscape is to deny humanity. Even though the landscape's relative dearth of biodiversity should distress us. An honest assessment of the region's postmodern ecology and significance requires acceptance of ambiguity and contradiction. Light turns his lens on this heterogeneous landscape and others similarly complex.

Michael Light

"Conoco Phillips Wilmington Refinery Looking South, 139,000 Daily Barrels, Terminal Island in Distance"

2006

Pigment print on aluminum

24 x 30 inches (or 40 x 50 inches)

In "Conoco Phillips Wilmington Refinery Looking South, 139,000 Daily Barrels, Terminal Island in Distance," a photo included in the book, "Rancho San Pedro, 04.28.06," a community baseball diamond seems incongruous surrounded by the expansive industrial complex of the southern Los Angeles basin. "Bayonne Golf Club, Former Landfill With A $200,000 Initiation, Old Standard Oil Refinery Beyond, NJ, 2007" pictures one of the Meadowlands' many landfills, in this instance reclaimed as an exclusive club, a manufactured escape in a landscape dominated by what most of us would deem the more mean marks of manufacturing. But the relationship of one to the other is not so dual; this isn't merely attractive versus ugly, good versus bad, or natural versus artificial. Light's photographs remind us that, like the refinery, the golf course and, indeed, even the glacial channel, qualitative judgments are in forever in flux.

Michael Light

"Bayonne Golf Club, Former Landfill With a $200,000 Initiation, Old Standard Oil Refinery Beyond, NJ, 2007"

2007

Pigment print on aluminum

24 x 30 inches (or 40 x 50 inches)

Take, for example, my long-held presumption that Los Angeles is a town with no shared pulse or sense of community. "Los Angeles, 02.12.04" carries Light (and us with him) northward over the industrial sprawl of Long Beach to the grouping of towers that comprise the city's downtown. Monuments to things bought and sold, the tall buildings rise from the city's otherwise low profile, each labelled: BP, Citigroup, Paul Hastings. Moving northwest, Light flies by the hills of Hollywood, dotted with the precariously situated houses of the rich and famous. I've never had a particular urge to explore this city, but as I turned the substantial pages of Light's book, the seismic beauty, fragility, and violence of the landscape were readable. Los Angeles became a romantic notion, an ongoing, astonishing experiment. The prints highlight the tenuous hold humans have on the land and, more generally, on our fate.

There is something freeing in the contemplation of our inevitable annihilation. Christopher Cokinos wrote recently in Orion that viewing extinction as an inevitability (and, therefore, civilization as a temporary exception) "nurtures sanity." I agree. Some readers will undoubtedly feel that this attitude is pessimistic, even nihilistic, but, to the contrary, I believe acceptance of our absurd position nourishes a desire to contribute, to participate directly, even in small ways. Faced with an impossible prospect, it is individual effort and happiness that sustain us. As Albert Camus concluded in The Myth of Sisyphus, "The struggle itself is enough to fill a man's heart. One must imagine Sisyphus happy."

Michael Light

"Carson Sink at 1000', 1600 hours, Fallon, Nevada; July 2000"

2000

Pigment print on aluminum

24 x 30 inches (or 40 x 50 inches)

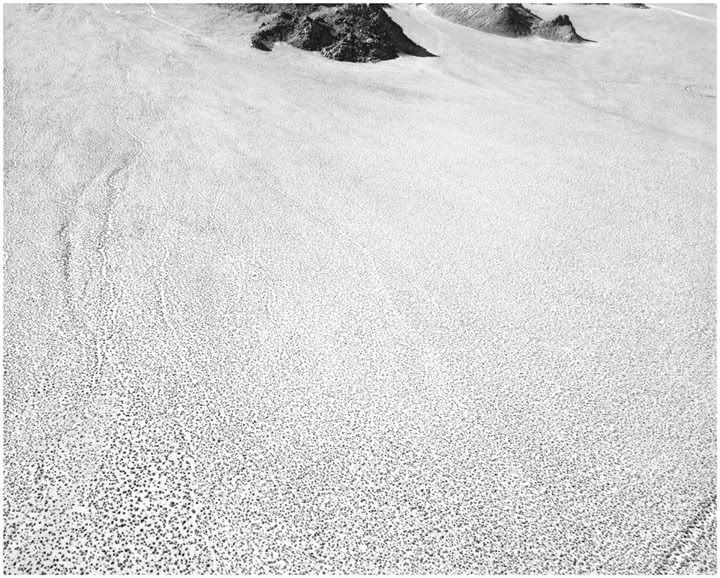

Each of us is part of a greater body. The rest of the material world is part of this body, too. I conceive of this corporate entity as a chaotic harmony. As I consider the pictures included in "Some Dry Space, 2003," serene portraits of one of the more severe, inhospitable ecosystems on our planet, I vacillate between macro and micro world interpretations. I recognize the desert landscape with its dunes, tracts, and other marks of the wind's work, yet the same photograph might also be seen as a cross section of a cell or a tissue slice. Contemplating this analogue, I find myself dusting off the childhood mindblower, “What if our universe, and everything we know, is contained within a marble in an alien universe?”(2)

Michael Light

"Bingham Mine/Garfield Stack, 04.21.06"

2006

Hand bound pigment prints, custom box

36 1/2 x 46 1/2 x 1 1/2 inches (open)

But such wonder shouldn't be limited to childhood. These desertscapes, like the spectacles within our bodies or the Hubble views of the vast beyond, present us with stunning beauty. For this reason, the scale of Light's bookworks is important. The viewer can take in the whole picture at once, thereby making it apprehensible and safe, but the book spreads are also large enough to be confrontational. The artist writes that he feels a "tempered awe" when taking these pictures. Remarkably, the bookworks succeed in translating that feeling.

I left Hosfelt Gallery thinking about the ultimate futility of the preservationist impulse. Time moves oblivious. Describing the tenuous state of Louisiana’s coastal wetlands, a civil engineer opined recently that many millions of dollars will be spent “to hold the line in the mud.” Indeed, our situation is literally and metaphorically futile, but Light's images remind us that our desire to hold that line, to preserve the landscape that shapes us (as we shape it in turn), is as natural as the change we react against. This absurd desire is itself part of the holistic landscape. As Howard Bloom wrote, "We are Nature incarnate."

Michael Light

"Garfield Stack, Oquirrh Mountains and Ancient Beach of Great Salt Lake"

2006

Pigment print on aluminum

24 x 30 inches (or 40 x 50 inches)

+++++

(1) And because people watch television indoors, the nature they witness becomes an irrelevant but entertaining outside experience, one external to or apart from contemporary living and ritual.

(2) This "deep thought" is presented well in the animated closing sequence of the comedy, "Men in Black." The camera draws back, out of our solar system and past countless others to reveal that the whole of our galaxy is contained within one marble. The marble is being used in an alien game of marbles, and each of the marbles used to play the game contains countless other solar systems and galaxies. Physically this makes little sense, but it nicely illustrates the scalar continuum.

Photo credits: All images courtesy the artist

4 comments:

Speaking of marshes, last weekend I finally made it to Jamaica Bay for the first time. Oh, what I've been missing! With our relatively pedestrian birding skills we were still able to identify around 30 bird species or so -- lot's of egrets, osprey, and poison ivy too -- very exciting. I think my favorites were the black-crowned night herons; very odd-looking birds. It's frustrating to think that the marshland there is rapidly decreasing.

Great prose to accompany the superb photographs. The last scene in MIB is one that I will never forget and it gives me endless fascination to ponder on it sometimes...

Jason:

That's terrific. Please let me know when you're heading out again.

I've never painted a black-crowned night heron (Nycticorax nycticorax), but a yellow-crowned night heron (Nyctanassa violacea) appears in "from the tangled vegetation." They're both fun species to watch go about their business.ag

but a yellow-crowned night heron (Nyctanassa violacea) appears in "from the tangled vegetation."

Ha! Very cool painting.

Post a Comment