The gateway to all understanding."

-Lao tzu, "Tao Te Ching"

In New York, recent mornings have greeted us with a pleasant chilliness. Fall is almost here, and winter is just around the corner. For most folks, the prospect is daunting. Not so for me. Each year at this time, a bounce finds my step and I'm happily overwhelmed by a spate of ideas. I know, however, that the creative juices will before long transmute into keen brooding. Late fall and winter nurture a pensive mind.

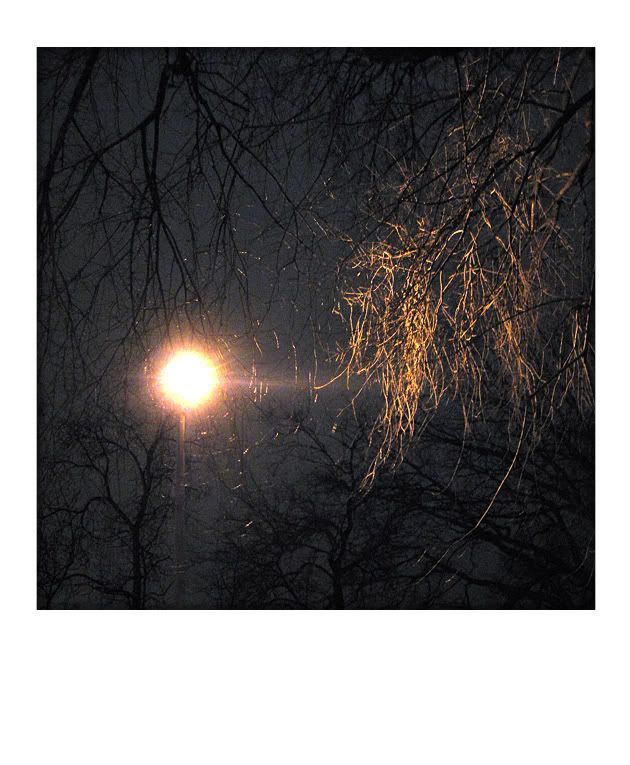

When the afternoons darken and the mercury dips, I like to take bundled winter strolls through the streets of Manhattan or Queens. Other pedestrians hustle about, intent on achieving their respective indoor destinations, but I find my thoughts best served by a steady pace, one forgiving of some intentioned aimlessness. I spend these walks looking up to where the melancholic sky meets the buildings that scrape it, admiring the resilience of foraging House sparrows, taking note of the way traffic lights glow more brightly in crisp, cold air and marveling over the many lives that move around me. I like to think of this mindful meandering as a form of prayer, or perhaps a communion, and I treasure the insights that are sometimes happened upon.

Curious about the rites, beliefs and texts of various religions (and particularly those of Judaism), I've been thinking this week about the coming high holy days. Next Monday is Rosh Hashanah, the first of Judaism's ten "days of awe," or Yamim Noraim. Like my winter walks, the Yamim Noraim are given over to contemplation. During the ten high holy days, an observant Jew should meditate on the actions of his last twelve months and, then, on Yom Kippur, the last of the "days of awe," fast and repent for any wrongdoing. In other words, a conscientious Jew begins the new year by reckoning with his past. Although Rosh Hashanah is only one of four Jewish New Years, each attached to a specific set of guidelines and meaning, I find the holiday's position with regard to the seasons of particular interest.

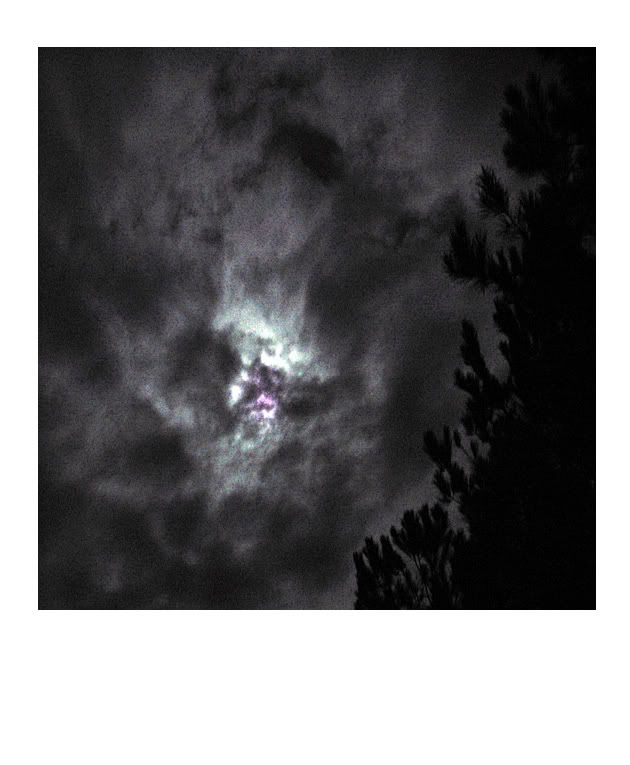

Considered the New Year for humans, animals, calendar calculation and contracts, Rosh Hashanah arrives with the ploughing of summer into fall. If one considers fall equivalent to dusk and winter to night, then the Jewish New Year, in the northern hemisphere, like the Jewish day, begins at twilight. This interpretation does not hold with regard to the geography and climate of the Torah's narrative; Palestine is (and was) a land with only two notable seasons, called in the Talmud "the days of sun" and "the days of rain," but our understanding of scripture, be it theological or scientific, must change with context if it is to remain relevant to our contemporary lives. The notion of a day extending from sunset to sunset runs slightly counter to the popular conception of morning time as a birthing, or spring, with the hours moving then through summer at mid-day, fall in the evening and finally into winter, night and death. But the Judeo-Christian tradition is pastoral, founded on an agricultural reckoning of the lunar and solar cycles. It makes sense, then, that the day should end as light fades or vanishes, and begin again while it remains dark. In rural farming communities, this pattern holds today, though the blue glow of television has altered habits in even the most rural of counties. Still, as Oscar Wilde, a consummate urbanite, quipped, "people in the country get up early because there's so much to do. They go to bed early, because there's nothing to talk about."

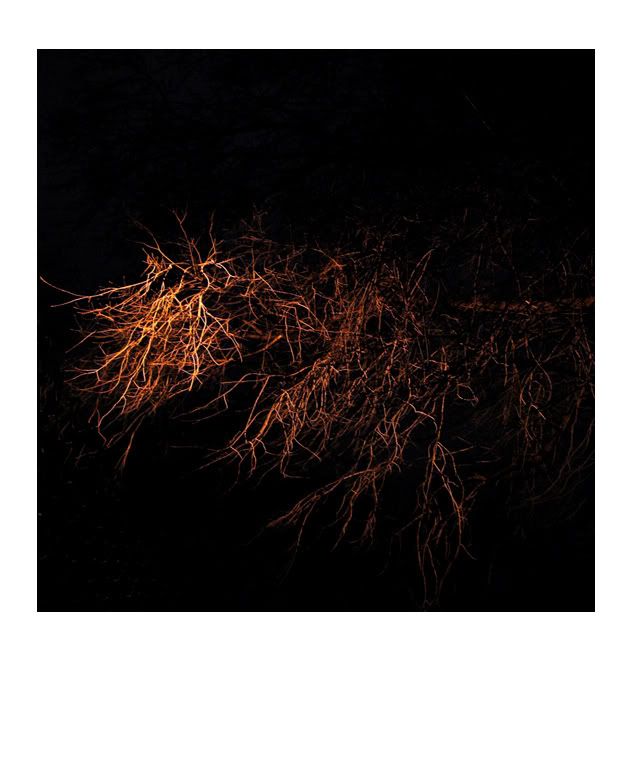

Growing up in such a community, I learned early that if twilight is a conclusion for the farmer, it is a commencement for many other creatures. A patient hunter who remains in his deerstand as the final light retreats might see bats dart and dip in aerial pursuit of insects. He may also see an opossum, fox, raccoon, skunk or even his intended quarry, deer, though it is not legal to shoot after the sun sets. Driving or biking on "backroads," these animals reveal themselves by reflecting light from a car's headlights or a bike's front beam. The tapetum lucidum, a layer of tissue behind the retina of crepuscular and nocturnal species, allows the animal to see better in near or total darkness, but this layer also produces eyeshine that discloses the creature's presence to human torch bearers. Depending on the species and the angle of approach, we can identify the animal by the color of its eyeshine: the white-yellow lights at knee height belong to the red fox; the orange orbs in the low branches of a tree are an opossum; the yellow beams tall over the road are white-tailed deer; the brilliant white spots that appear so near the ground expose a resting whippoorwill.

Imagine the shock of the early humans when they first noticed the glowing embers that moved just outside the reach of their warm firelight. The agricultural tribes that would become the people of the Torah, having abandoned much of their nomadic, hunter-gatherer roots, were particularly afraid of the dark, creeping world outside that circle of light. To be caught in the gloaming, away from a human settlement or encampment, was surely a terrifying possibility.

Indeed, the dark months, like those black, antediluvian nights, remain an ordeal for many people . But they can also be understood as a gateway opportunity. It is fitting, I think, that Jews begin their new year by taking stock, a formidable task if undertaken with thoroughness and honesty. I approached my experiences with hallucinogenic drugs in an analogous way; what most people would call a "bad trip," I viewed as an opportunity for introspection. 'Why has my brain created this awful idea?,' I asked myself. 'What does that tell me about my relationship to x or y, or about my fear of a, b or c?' The cold, gloomy months, like bad trips, nightfall and deep melancholy, can be challenging, even endangering, but in an increasingly mediated and accelerated world culture, the difficult passages are of premium value.

I'm neither Jewish nor properly Christian, despite an Episcopal baptism. I wouldn't describe myself as lapsed, either; from early adolescence, I proudly labelled myself an atheist. Today, however, I prefer the term pantheist, and I find my interest in faith choices and spirituality reinvigorated, though my conception of God is fundamentally unchanged from my Nietzsche-Nine Inch Nails days.

I've taken particular interest in Jewish practice, both historical and contemporary, although the concept of an omniscient, interventionist creator is anathema. Unitarian Universalism, a relatively young sect that grew out of Unitarianism, is also exciting to me, though it is so all-inclusive and plural - Christian, Muslim and Jewish believers sit in UU pews alongside Buddhists, atheists and agnostics - that it might be more fairly deemed an ethical community than a religious sect. But whatever label I eventually pin to my lapel (or discard), periods of solemn self-examination are likely to remain a critical part of my identity and annual experience, and these have so far coincided with winter and come on the heels of a fall surge in the creative impulse.

Although modernity misunderstands fall to be the beginning of an end, it is only another beginning. Shana tova umetukah, folks. My favorite season is moving in, and our shadows grow longer.

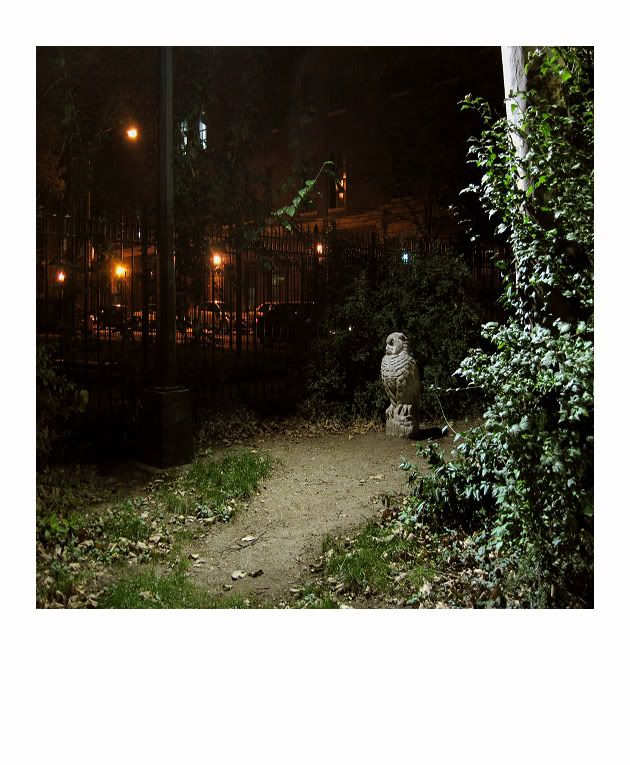

Photo credits: "Athens Park, Astoria," "Central Park, Manhattan," "Heron's Foot Moon, Virginia," "Branches," all by Christopher Reiger, 2007 and 2008

No comments:

Post a Comment