|

| Snapshots From Home Ground Chapbook, 2013 |

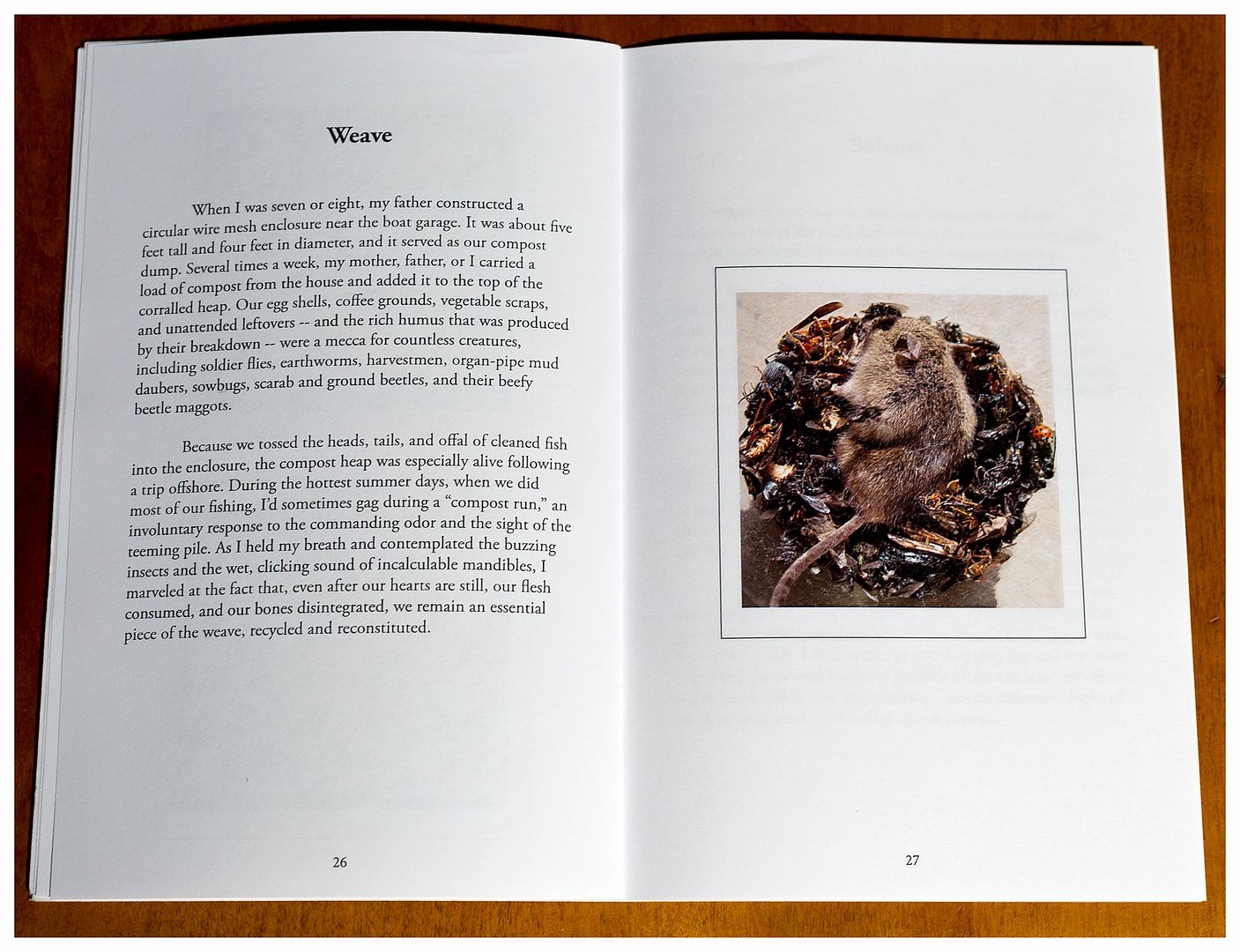

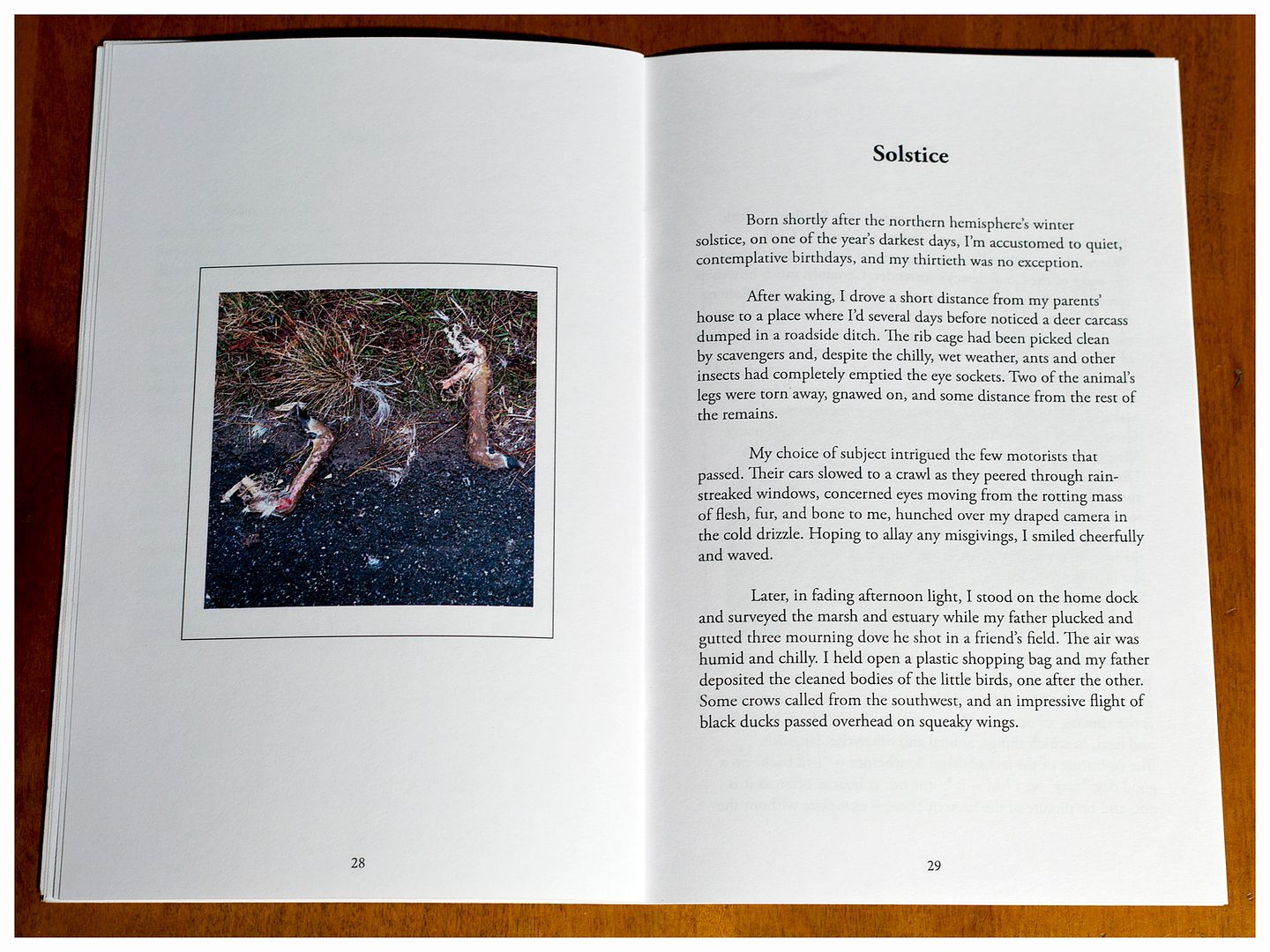

Snapshots From Home Ground, the limited edition chapbook I produced in conjunction with the Aggregate Space Writer-in-Residence and Featherboard Writing Series, was released in early August 2013. A meditation on my rural upbringing on the Eastern Shore of Virginia, the book is comprised of eight vignettes and a selection of photographs taken by either me or my father.

Copies are available through both Aggregate Space and Featherboard. (I also plan to release a free e-chapbook version later this year.)

Below, I've published "Good Boy," the chapbook's opening sketch, and also include a number of "snapshots" of book spreads.

Good Boy

The black lab wandered out of the pine grove near the chicken yard.

It was mid-morning on a humid and already hot summer day, and I was helping my father with chores when I saw the dog. In the country, an unfamiliar stray is cause for concern. For an eight-year-old boy, however, the lab represented a potential playmate. Seeing me, the young dog galumphed my way with the spiritedness characteristic of his breed. I laughed as he waggled, whined, and gamboled his way around me.

Perhaps I attributed the lab’s oily looking fur and its odd licking behavior to the temperature. Whatever I thought, I failed to identify a very sick animal. Rabies, in its early, prodromal stage, is a different beast. The frothing, biting monster that runs wild in our imaginations is real, but that stage, called the “furious phase,” comes later. Nonetheless, by the onset of the prodromal period, the virus has already reached the animal’s brain. My father, less interested in new playmates, recognized the dog’s symptoms and quickly relegated me to the house.

I stood on the bleached brick of our air-conditioned back porch, hands pressed against the sliding glass door, and looked across the farm’s expansive backyard to my father’s parked pickup truck. Its rear gate was lowered and, some yards behind, my father stood in front of the lab. From the porch, I didn’t have a clear view of the proceedings, and I don’t recall whether my father was holding a .22 revolver or a rifle. The close range makes the handgun the better tool for the job; in my mind’s eye, that’s the weapon wielded. In spite of the insulating glass doors and the thrum of the air conditioning, I winced at the sharp crack of the gun’s discharge, and the rest is bits and pieces.

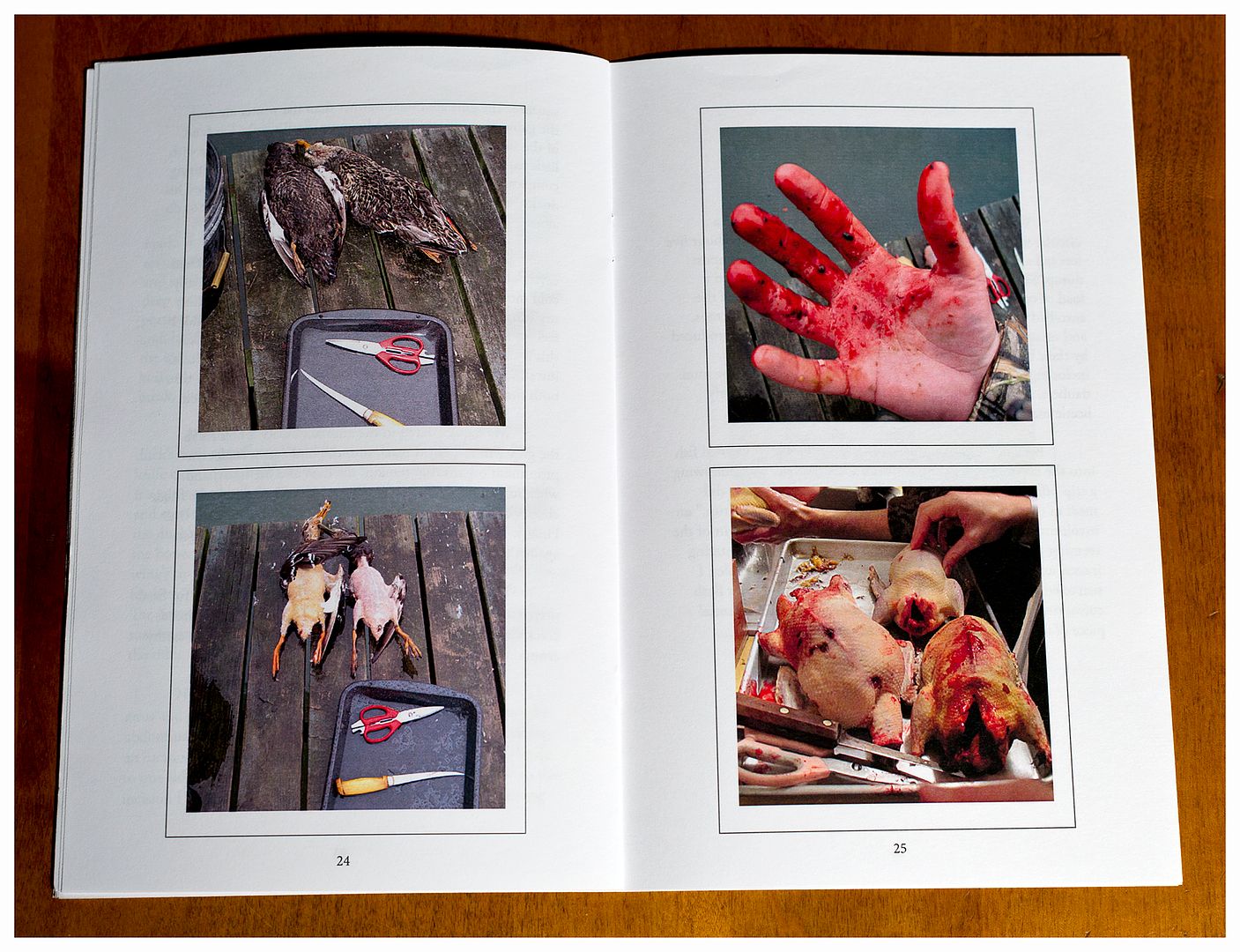

I remember the greasy fur of the dog, who in death, no longer exuberant and bounding, appeared so plainly unhealthy. I remember the blood pooling a vivid scarlet in the ditch-like grooves of the truck bed. I remember my dismal mood.

I cried and brooded, quietly raging at the arbitrary nature of a world in which a young animal, man’s proverbial best friend, could be infected with an untreatable and fatal virus. I displaced some of this existential angst onto my father. He’d already taught me that creation is capricious, but the sentiment didn’t sit well with me as a child. I was afraid of death and I found the tales of a naughty or nice Hereafter compelling. In the case of the lab, I imagined that he’d been a “good boy,” and I took solace in my belief that at least all good dogs go to heaven. But my father dismissed talk of afterlives as fearful pap, and, in time, despite the countering influence of my mother, I, too, would grow leery of the faithful around me.

We drove the body to one of the farm’s back fields and left it on the margin for a kettle of turkey vultures to descend upon in their tilting orbits. It didn’t occur to me on that sad and sweaty morning, but those dark, bald sentinels of the sky, who visit earth to feed on carrion and carry the reconstituted energy skyward again, offered a consolation that literalist religion could not.

Image credits: Christopher Reiger, 2013

No comments:

Post a Comment