It’s difficult to summarize a first visit to another country. The challenge is compounded when the country in question is culturally and geographically "on the other side of the world." Any thoughts that I put down on paper are too neat. They're in no way comparable to the messy musings of this traveler when I was still abroad.

Unfortunately, if I do not write about such trips, my experiences quickly become vague, fading to the point of inapplicability or cocktail party conversation – “Oh, Christopher went to Japan a couple of years ago, didn’t you?” For me, the best trips are an education (as opposed to a vacation) and I'd rather risk forwarding an especially obvious observation than abandon the memory.

I’ve long been fascinated by Japanese culture and was therefore eager to see the country and the people for myself. Many of my assumptions proved accurate – no great feat in the age of globalization – but it would be disingenuous of me to claim that everything I was presented with - custom, food, place - was unsurprising or even to my liking.

Cleanliness:

Cleanliness:Japan is a very clean country populated by a very clean people. Several times, I saw loose paper or plastic chased down and pocketed, presumably for proper disposal. The first time that I saw a subway employee scraping discarded gum off the sidewalk, I was struck by two things.

1) This was the first "litter" that I'd seen in Japan.

2) A foreigner must have dropped the gum. (This isn't necessarily true, of course, but the idea of a Japanese person carelessly dropping garbage on the ground is anathema.)

The relative absence of litter is that much more impressive when one realizes how few public trash receptacles are readily available in Japanese cities. Granted, I'm used to

New York City, where most street corners are home to a trash bin. In

Tokyo, on the other hand, I sometimes carried empty cans or plastic trash for hours before spotting a receptacle.

That said, plastic drink bottles are easy to dispose of. Most vending machines - the usual source of the bottles - have a recycling container positioned nearby. I was also impressed by the recycling ethic; I rarely saw a receptacle that was for "general" rubbish. Most bins are labelled; plastic bottles, steel cans, plastic, combustibles, and paper all find separate homes.

Timeliness:An unsurprising confirmation of an established stereotype: many Japanese people adhere to a strict schedule. Lateness is unacceptable. While I find this altogether refreshing, it isn't necessarily a social good. Two of my Japanese friends, both of whom have also lived in the United States, view the timeliness obsession with ambivalence. A friend told me of a recent accident involving an agitated, young subway conductor. Having fallen behind schedule (by just a minute or two), this conductor attempted to make up the difference by racing the train to the next stop. In doing so, he gained enough speed to derail the train, which then crashed through the basement of an apartment building. A number of the commuters on board were killed. According to some recent studies, schedule related stress also takes a toll on Japanese city dwellers. (Of coruse, I assume that the effects of stress on urbanites

everywhere are similarly negative.)

Convenience Stores:Daily Yamazaki,

Family Mart,

AM/PM,

Sunkus and

Circle K all became regular stops for me. In these one-stop shops, you can buy just about anything you need. These stores are not your standard-issue

7-Elevens, another chain which has

colonized Japan.

The "combini," as they are called, offer more variety than their American cousins, even though the total stock is equivalent in size. In the States, convenience stores usually allow us to choose between junk food, junk food and, well, junk food. At combini, I could buy junk food, fresh sushi, or balanced box lunches which would cost a pretty penny here in the States. And buy them I did. When I wasn't eating at a restaurant, combini offered an inexpensive, healthy option.

True vegetarian dishes were hard to find, unfortunately. I would buy a rice wrap, for example, thinking it was simply rice wrapped in seaweed, only to be surprised by the salmon hidden in the middle. As a result, I several times (unwittingly) broke my dietary restrictions.

Population and Sprawl:

Population and Sprawl:The Japanese have devised aesthetically pleasing ways of dealing with concentrated population, but the small living spaces and stacking necessary for such a feat often strike Westerners as curious. For my part, I like small houses and small rooms, but the notion of a "back yard" doesn't seem to exist in the suburban sprawl surrounding

Nagoya or Tokyo. In fact, "

front yards" are absent, too. You do see small, immaculate gardens, however, which make the neighborhoods quite inviting despite their similarity to our own American brand of suburbia. Strip malls, chain stores and unnecessary traffic signals are also common.

Cities like

Kyoto and Nagoya felt no more crowded than

Boston or

Atlanta, but Tokyo is a nightmare for those folks, myself included, who don't care to find themselves set down in a sea of humanity

sans greenery.

From the viewing tower of the

Tokyo Municipal Government Building I realized just how large Tokyo is; it dwarfs New York City both in population and area. Tokyo, with an area of about 2200 square kilometers, has 8 million full time residents and, during the workday, a total population of 12 million. The workday population of New York City, having an area of just 1200 square kilometers, tops out around 8 million.

"Ticket Punchers":A good friend describes the Japanese as a “nation of pointers” and the stereotype of the Japanese tourist/photographer suggests that my friend is not alone in his assessment. I prefer the term "ticket puncher." During each of my trips to

Central America, I met compulsive

birders on a quest for certain species they "needed" to add to their "

life list." I enjoy birding immensely, but I've never appreciated this competitive, cataloging approach, as it lessens the likelihood for real learning and substantive communion. Whatever the case, there are many birders of this stripe; some of them actually call themselves "ticket punchers." They'll say, for example, "Well, I finally saw a

Resplendent Quetzal today...got my ticket punched on that one. Gonna head to the coast tomorrow and see about knocking off a

Magnificent Frigatebird."

The Japanese experience isn't so much different. Whether "knocking off" a monument with a photograph or pointing excitedly at a zoo animal, they seem to take very little interest in any signage or prolonged observation. Point, click, shuffle on to the next "sight." Once there, it's point, pose, peace sign, click, shuffle on to the next "sight." And so on. Of course, this approach is largely shared by contemporary Westerners, too, especially in our global culture of distraction, but I condemn it in us and therefore see no reason not to condemn it in the Japanese. It's fundamentally thoughtless and incurious.

Telephone Lines:

Telephone Lines:One sometimes hears recent travelers to Japan remarking on the oddity of the country's above ground telephone system. In a country as technologically advanced as Japan, it seems strange that so much land should be covered with a haphazardly constructed spider-web of communications lines.

This arrangement contrasts sharply with the United States and most of Europe, where communications lines are usually buried, especially in urban locales. Looking up, one doesn't see dangling wires and lines crisscrossing the blue canyons of New York City, for example. In Japan, even lounging in an outdoor

onsen in the small mountain town of

Toei, I gazed up at tall, steel telephone towers. Wires are strung tightly from one tower to the next, and these towers march over and around the country's mountains.

Surprisingly, I didn't find Japan's above-ground communications system aesthetically troubling. (In some areas, it's even attractive!) But I believe I'm in the minority. Furthermore, aesthetics aside, the installation and maintenance of all these towers plays havoc with the already stressed mountain slopes.

Erosion of hillsides/mountains:

Erosion of hillsides/mountains:It seems that every mountain and hill in Japan - with the exception of

Fuji - has been manhandled. The principal culprits are road construction and the ever-expanding communications network. The activity causes the mountainsides to erode at an alarming rate. In response, trees are cut down and stacked to serve as barriers. When these barriers fail, as they eventually do, local engineers cover the eroding slope with wire mesh or spray it with a plaster-like mixture to halt further subsidence.

Japan's equivalent to U.S. "

pork barreling" results in a lot of federal funding for local works projects, devised to inject money into rural economies and keep constituents happy. Not surprisingly, many of these projects are thoroughly unnecessary and only further degrade sensitive areas.

Hybrid/Bio-diesel and the Marketed Greening Revolution:While I can't confirm (and don't believe) that all Japanese cities have taken the same steps that Kyoto has, all buses and taxis in Kyoto are either hybrid or biodiesel vehicles. I saw some evidence of a similar transition in Tokyo and Nagoya, but I'm not sure implementation is "across the board" in these cities. Though encouraging, I hope Japan won't rest on it's laurels; it has an opportunity to lead the world in this arena.

Throughout the country, the "green" PR spin was in effect. Signs announcing the dawn of a ecologically harmonious age dotted city blocks. This may be the result of the

2005 World Expo, currently being held in Nagoya. The Expo's theme is the environment. At the Expo, I visited several corporate pavilions ostensibly devoted to "green" research and technology. Not surprisingly,

Toyota led the pack, featuring new fuel-cell vehicles alongside their robots and walking human carriers, but other companies also championed the push for "green" reform. One couldn't help but be suspicious. I fear such doubts are well founded; the pavilions stunk of snake oil.

Vending Machines, Panties and Porn:With some sorrow, I have to relate that one of my favorite Japanese peculiarities is either true no longer or altogether apocryphal. Vending machines selling used panties were nowhere to be found! While you

can buy a great many things from Japanese vending machines, I found none of the items offered particularly surprising. Sure, it's unusual for an American to see beer and cigarettes available so readily - insert Yen and out pops a brew - but it's not exciting. I asked several people - guys and girls both - about the rumored "pantie machines." Everybody laughed off the notion as a popular myth. Alas, that photo I so wanted to take will have to remain unrealized.

In any case, I'm sure it would have been a short-lived thrill. The first time that I noticed a Japanese business man looking at a porn magazine next to me on Tokyo's public transit system, I thought only, "Huh...well there you have it."

Proximity of Suburbia and Localized Agriculture:

Proximity of Suburbia and Localized Agriculture:On my first evening in Japan, I took a stroll with my friend Ben in his Nagoya suburb,

Seto. The landscape's most striking feature were the many rice paddies, everywhere butting up against apartment buildings and roads. We walked along dikes that divided broad fields surrounded by houses, restaurants and combini stores.

This sort of localized agriculture is very much a part of the Japanese landscape, whether urban or rural. Excepting city centers, it is not uncommon to see planted fields and vegetable gardens throughout Japan, even in areas dominated by commercial ventures. In the United States, an equivalent scenario would set corn and wheat fields amidst suburban population centers like

Alexandria, Virginia,

Westchester County, New York,

Cambridge, Massachusetts or

Berkeley, California.

Because of this comfortable relationship between "cultured" human settlement and agriculture, the nighttime noises of suburban Japan are not that much different from those of the countryside. Many species of amphibian, bird and insect frequent the edges of Japanese cities and suburban neighborhoods. While some readers may feel the same can be said of the United States, our brand is absent the biodiversity I observed in Seto.

Bad teeth:"

British people have terrible teeth." We've all heard it said and most of us (especially Americans) agree with the generalization. Most

Brits counter that Americans have an unhealthy, frivolous obsession with the cosmetic. In other words, we're all vain fools.

Despite having had braces briefly as a young boy, my wisdom teeth (still intact) shoved several of my front teeth out of place. Though it may be considered unsightly by some, I couldn't care less...so long as I have clean, healthy gums and no cavities. Admittedly, I'm not a good example of your everyday American; many of us

are obsessed with cosmetic concerns.

Still, most dentists, British or otherwise, agree that much of the British oral "problem" is due to negligence. In the States, a dental visit every six months is considered normal, almost mandatory, whereas many older Brits pride themselves on having gone for a cleaning only a few times in their lives.

Well, the Brits ain't got nothing on the Japanese. Crooked teeth and odd bridges - crude looking metal installations - are considered "cute" in Japan. This is an understandable reaction to an unfortunate reality. Japanese children often experience extensive tooth decay and, while medical care in Japan is very good, the same can not be said of the country's dental care. I was shocked by the gross crowding, discoloration and fillings I observed. Having traveled to several very poor countries, I've spent time with people who have received no dental care in their lives; their teeth were healthier than many, if not most, of the Japanese people I saw.

Halitosis is also a serious problem in Japan, owing to the poor oral care. As Dr. Kazumi Ikeda, a practicing

orthodontist in Tokyo, puts it, "The Japanese have much poorer oral conditions than not only westerners but people in less economically developed nations."

Thankfully, this is changing. Future generations of Japanese will have increasingly healthy teeth. Go, go globalization!

Trust:The Japanese are a trusting, honest people. As evidence, I submit the following examples.

I rarely had my

JR Railpass (Japan's equivalent to a

EuroRail Pass) inspected by train conductors or station personnel - even when I mistakenly boarded the reserved "super express" train - and when I couldn't locate my friend's keys after he left for work, he suggested I just leave the apartment door unlocked when I left.

The crime rate in Japan is very low and "good faith" stories abound. For example, a wallet forgotten on a restaurant table is usually in the same place when the panicked owner returns. More noteworthy still, a couple from

Singapore I met told me that a Japanese woman had covered their station locker storage fee ($5.50) when the first locker machine they tried had proven faulty. Without another 600 Yen between them, they didn't know what to do. As I understood it, the Japanese woman intervened because she realized the couple was planning to leave the country that afternoon. They wouldn't have time to straighten things out with the locker company, so she payed for a new locker and gave them her address! Then she was on her way.

Interestingly, I several times found myself in a position where I could have elected to "pull one over on the man." Often in New York City one feels good about finding a five dollar bill on the sidewalk or getting a free subway ride. In Japan, though, I did not feel like taking advantage of such situations. (Of course, I did keep my mouth shut about the "super express" train, because had I been caught I would have been out a considerable sum and my transgression was totally innocent, a result of my poor Japanese.)

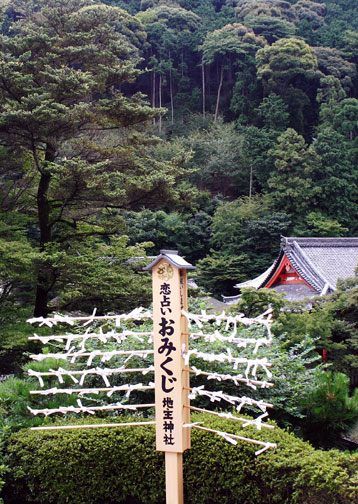

Photo credits:

Photo credits: all images, Hungry Hyaena, 2005