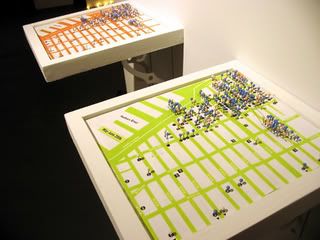

Jennifer Dalton

"Art Guide"

2006

Map, colored pins, painted wooden frame

9 1/2 x 10 1/2 x 1 1/4 inches

Of late, there's been a lot of protest, commentary, and debate concerning the shamefully low percentage of women showing in the art world. It's true; the contemporary art world is dominated by men. Furthermore, I'm assuming that the majority of these men are heterosexual Caucasians, meaning the art world, reflecting the 20th century American teenagers read about in their high school textbooks, is white, male, and straight.

The art blogging community, ever expanding, has fed well on a steady diet of relevant posts, especially following the publication of Jerry Saltz's recent "Where The Girls Aren't" piece in The Village Voice. I generally enjoy Saltz's writing, and this piece is no exception. Saltz writes, "According to the fall exhibition schedules for 125 well-known New York galleries—42 percent of which are owned or co-owned by women—of 297 one-person shows by living artists taking place between now and December 31, just 23 percent are solos by women." Wow; that's astonishing and embarrassing, especially when I note that 60 percent or more of my artist friends are women, and I feel this number representative of the working artist population in New York, if not the United States at large. We have reason to take stock of the situation; there is no ignoring the numbers.

And yet, I can't help but feel the subject itself a bit, well, dated. Is the sex (or sexual preference) of an artist still so important? I mean, sure, most folks across our great, prudish nation are very concerned with sex and sexuality. Debates rage about female golfers on the PGA tour and the sexuality of politicians. But we're not talking about the general public here (no matter how much I'd like the art world to expand it's reach). The voices involved belong to a relatively small, very progressive group of educated individuals.

The question may sound a bit naive, but why are we still "seeing" skin, sex, or sexuality in art that doesn't focus on these issues? Frankly, most art that does take on these issues is didactic, a breed of intellectual illustration which, while worthy of consideration, fades from memory and relevance in much the same way an excellent piece of journalism does. By contrast, most artwork I see these days, whatever the medium, lacks an overt agenda. Until I see the name or, in some cases, until I read the press release, I don't know much about the maker's makeup. Frankly, I don't care to. The art will either ring my bell or it won't. If I later learn about the artist's background and find that these details inform the work further, hooray, but until I want to peel back that layer, I don't need to know hooey. Art, I feel, is a beast best viewed apart from the artist.

At times I feel like shrugging off the issue. Shouldn't we be concerned with the product as opposed to the personality or biography? Yet the imbalance of the sexes is real, and it mustn't go ignored. I'm proud to be friends with ambitious artists and curators who are devoting energy and thought to addressing and, hopefully, rectifying the problem. Still, I can't shake the longing for that day, a millennium or more on, when miscegenation and a dissatisfaction with ol' time fundamentalism will result in our wearing one skin and being more tolerant of varied beliefs. Maybe then we can set to the business of real - meaning global - humanitarian and environmental progress...and artists can expend more energy thinking about art rather than who made what and why.

Photo credit: ripped from Winkleman Gallery; Normally, I would have asked Edward for permission, but he's out of the country and without frequent Internets access...and I'm compulsive.

5 comments:

Frankly, most art that does so is didactic ... fades from memory and relevance in much the same way an excellent piece of journalism does.

Does excellent journalism really fade from memory so easily? Isn't most of what we know, the near entirety of our collective intelligence, a reflection of forms that intended to educate, and that not only didn't fade from memory and relevance, but form the very core of our basis for perception?

The voices involved belong to a relatively small, very progressive group of educated individuals.

Unfortunately, the problem probably stems from the top of the art system (also, gallerists, as a group, are much less progressive than they may appear, just look at employment practices within most galleries). As long as the driving forces behind the art world (the absolute elite of the elite, the filthy rich from the Old Men's Club; i.e., see Auction Price Trends) are misogynists, their seemingly old fashioned form of hierarchical oppression will continue to exist as dictated from above. Most gallerists probably see themselves in a kind of market-driven Catch 22. There is much that gallerists can do to curb discrimination within their own galleries, but in order to eliminate the problem entirely art players (including artists, gallerists, critics, etc.) will have to stop capitulating to a small group of woman haters. This is much easier said than done, but efforts by groups such as the Guerrilla Girls should not be discounted.

Many of us want to live in a world free from sexism, but I doubt that pretending such a world already exists will make it so.

Jason wrote:

"Isn't most of what we know, the near entirety of our collective intelligence, a reflection of forms that intended to educate, and that not only didn't fade from memory and relevance, but form the very core of our basis for perception?"

I would like to agree, and think it well said, but it seems the individual journalistic accomplishments - be they educational television or revealing exposes in the pages of a newspaper - that comprise the collective progression are readily forgotten or disposed of.

We remember the changes that much good journalism helped foment, surely, but do we recall the articles themselves, much less the authors' names or their stylistic choices?

"Many of us want to live in a world free from sexism, but I doubt that pretending such a world already exists will make it so."

Absolutely, and I didn't intend to suggest that I do believe we live in such a world.

Dear Hungry Hyena

Please can you contact me --

jameswestcott@artreview.com

thanks

James

I was looking for the history of anthrozoology as a comparison in advocation of cryptozoology becoming a legitimate branch of zoology for a class I have and I found your site. It must have been Serendipity smiling at me(my brain needed an entertainment break)because I can't figure out how you ended up in my search. Anyway, I'm finding your site interesting and I'm infinitely jealous over the fact that you can keep up with such a journal.

As for my thoughts on females in the art world, I have to say as a female that I find most females to be typical in their art. Almost as if they're required by their sex to paint the same types of things over and over. I much prefer male artists as they seem to be so spontaneous in their work...well maybe not artists like Seurat who apparently mapped out their work...My favorite is Escher, his drawings create stories for me and I think that is what art is all about.

Oni:

Thanks for reading.

Your class sounds very interesting, particularly as our oceans turn back the clock, becoming more acidic, ripe for the return of ancient species, particularly those with relatively simple construction, such as microscopic weeds and slimes. (Think of all the reports, in scientific journals and the occasional newspaper, discussing the resurgence of jellyfish species and Lyngbya majuscula.) Cryptozoology could certainly grow in importance.

As for female artists, I can't agree with your assessment. I'd wager that you probably haven't seen a lot of work by women, and I assert this because I felt similarly to you before I was exposed to a wider swath of contemporary art. These days, some of my favorite artists are women, something unimaginable a decade past.

Post a Comment