I thought again of childhood in Union Square, where the rich smell of the Greenmarket's composting station roused amusing memories of the indignation I felt whenever asked by my parents, those years ago, to empty the compost. The sun was bright in the cold air and, as I walked south from the park, an invigorating chill slipped under my coat collar to quicken my step, broaden my smile and stir a contemplative inclination. At 11th Street, as I admired the Gothic revival architecture of Grace Church School, I slipped into a reverie about Earth's stray moons.

NASA researchers now believe that Earth once had three or more moons. The lost moons, or moonlets, were smaller than our existing satellite and, after orbiting Earth for up to 100 million years, they either crashed into our surviving moon or broke free from the planet's gravitational pull. In the latter scenario, the moons may have been drawn into and consumed by the sun; alternatively, they may have drifted into deep space. I prefer this last option, a vision of the moonlets soundlessly sailing through distant reaches of the universe. It's a lonely thought, but it is also serene, even happy.

Thinking about these content cosmonauts, it occurred to me that everything that morning seemed gratifying. After further consideration, I estimated that I'd been afflicted with this hearty disposition for at least two weeks. Although I generally characterize myself as an upbeat person, this bout of optimism seemed remarkable in both duration and degree. What gives?

Perhaps my wonderful girlfriend is responsible for these good vibrations, or maybe my renewed investigation of theology and philosophy is fulfilling some latent need? Maybe my acting on the long-ignored impulse to use half of all my art profits to support humanitarian and environmental work has made me more honest (and happy)? Perhaps, as some friends have suggested, I'm merely feeling the effects of Obamatism, optimism fed by the election and inauguration of Barack Obama. Whatever the cause or causes, the cumulonimbus clouds over yonder are dispersing.

But what a time to feel hopeful and appreciative! Today's global and domestic prospects aren't good, even when viewed through a rosy prism, yet I've emerged from the Bush oughties convinced that Aristotle's conception of eudaimonia is valid.

|

| Rembrandt van Rijn "Aristotle with a Bust of Homer" 1653 |

In "The Meaning of Life," Terry Eagleton's terrific (and fun) investigation of meaning, doubt, religion and postmodernism, the critic points out that Aristotelian happiness, "bound up with the practice of virtue," might be problematic in our postmodern, plural age. He asks if eudaimonia is fit only for colonialists or neo-conservatives, thinkers convinced that rectitude can be enforced by the sword and not generally given to consideration of "the other's" perspective. But we - that is, the rest of us - need to reclaim Aristotle's faith in essential human goodness. Despite Eagleton's playful nitpicking, there is no reason that compassion and moral progress should not (or can not) coexist. Call it Obamatism, call it naive idealism, call it what you will...but it's time to participate, to put aside our generation's infantilism and get to Aristotle's happy work.

Admittedly, it's egocentric and philosophically naive to believe that "your moment" is any more significant than the countless moments that preceded it, but precisely because it is your moment, such short-sighted thinking is natural; it can even be beneficial, because it compels us to participate more fully. In some respects, individual action is more important than its group counterpart. If that suggestion sounds wrong-headed, it is because the individual, as a concept, is much maligned by the ideological left. But the variety of individualism they decry is not the sort of individualism presently called for.

Our contemporary zeitgeist is dominated by me-centered iCulture, a globally traded, commodified version of individualism so clouded by consumerism that most of us struggle to identify our own significance, much less the significance of everyone and everything surrounding us. It's hard to rally to the call of the moment, to feel as though individual human agency has any bearing on what will come tomorrow, next week, next year or next millennia, when faith in yourself and others is so obscured. The apathy of Western culture is a bottom-to-top disorder, affecting the individual first and, then, society as a whole. But this apathy is a temporary side-effect of our rapidly globalizing and technologizing world. We will pass through our challenging stage of human social development but, fraught as it is, the need for an active and immediate commitment to bettering our world's future is great.

|

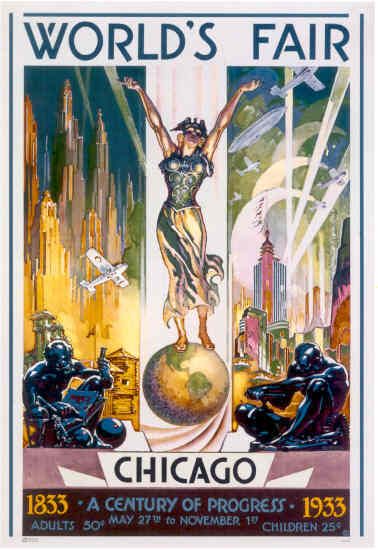

| Poster for 1933's Chicago World's Fair |

And what's become of that storied horizon? Michael Chabon eulogized "the Future" in his article, "The Omega Glory" (January 2006, Details magazine). "The Future was represented so often and for so long...that at some point the idea of the Future - along with the cultural appetite for it - came itself to feel like something historical, outmoded, no longer viable or attainable." The vision of the future also soured; the early twentieth century West's faith in the imminent invention of the flying car and the transition to a "benevolent, computer-assisted meritocracy" had mutated by the 1970s. "If nuclear holocaust didn't wipe everything out, then humanity would be enslaved to computers," Chabon observes. These dystopian scenarios were favored by fin-de-siecle science-fiction writers, but the fear that spawned such stories wasn't new; cries of impending collapse have sounded since civilizations began bumping into one another. The global dissemination of dystopia, however, was new, and it gave rise to a pandemic waning of confidence in the steady progress of man. Enter the doomsayers, those thoughtful folks who would see my eudaimonia wilt.

Saturday evening, after spending the afternoon ensconced in my studio, drawing and listening to NPR updates on the continuing violence and sorrow in Gaza, I sat down to read Ben McGrath's article, "The Dystopians." (The New Yorker; January 26th) McGrath profiles three of today's most popular doomsayers, Dmitry Orlov, James Howard Kunstler and Nassim Nicholas Taleb. The three men are intelligent, considerate and not at all lunatic, but they share a tragically bleak vision of our society's future. All "begin with the certainty that a side effect of globalization is 'fragility'" and conclude that our precariousness has carried human civilization to the verge of another dark age.

Orlov describes his audience as,

"belonging to three basic cultural categories: 'back-to-the-land types,' united in their opposition to industrial agriculture; 'peak oilers,' who worry about the shock effects on energy markets of reaching the maximum global crude-extraction rate; and all around Cassandras, or 'people who sometimes derisively are called doomers.'...In the past few months, Orlov has acquired a fourth audience, composed of financial professionals."Orlov's list, however, is incomplete. I don't fit neatly into any of his categories, yet I was a devotee of Kunstler's predictions for some years. Indeed, the ideas put forward by these prophets of collapse appeal to many environmentalists. McGrath writes that,

"[the] Malthusian movement has expanded with time into a kind of peaknik diaspora. Peak oil and peak carbon (i.e., global warming) are the heavies, with the most obviously compelling claims on our attention, and the greatest number of advocates; their relative standings swing in rough accordance with the price of gas and the latest hurricane news. Smaller contenders like peak fish and peak dirt have their devotees as well...The bailouts in the wake of the subprime defaults, however, have arguably thrust a new concern to the front: peak dollars, or the point at which the system breaks down through the simple printing of paper money."McGrath overlooks the granddaddy of all peaknik fears, peak population. But whatever your principal concern, once you find yourself wringing your hands about one of these anxieties, you'll find it easy to latch onto another. Trafficking in dire forecasts is often addicting; as McGrath puts it, "triumphant pessimism can be fun."

|

| Albrecht Durer "The Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse" c. 1497-98 Woodcut |

Are the bleak pictures painted by today's doomsayers the products of too much science-fiction or are they rational, if frightening reckonings of our species' excesses? A bit of both, I think. Though we celebrate the democratic and humanitarian legacy of the West's exuberant colonialism, itself a product of the Enlightenment, we must also recognize that empires, past and present, value most highly the accumulation of material wealth and the acquisition of social rank. According to cultural critic Morris Berman, the variety of democracy exported by the First World may be the most poisonous of all. Although extolled by Thomas Friedman in the pages of the New York Times, today's global, democratic economies are hierarchical and often brutal; in at least this respect, they are little different from early agricultural societies. Berman writes, "global-democratic-consumer culture is defined by acute social and economic inequality, declining marginal returns, and spiritual-intellectual disintegration."

As a result, in our imperfectly globalized world, calls for democracy, human rights and environmental stewardship are heard, but are often confused in the great din of reactionary, hateful yelling. The only universal myth is one of wanting. Berman calls this the "'democratization of desire,' the notion that all [have] equal rights to the world of comfort and luxury, and that this [is] what life [is] ultimately about." All of our contemporary tribes (religious, racial, ethnic, national and so on) vie for the same illusory zenith rather than agreeing that there are more sensible, generous uses of our energy. In the industrialized First World, the victor's spoils have created a poverty of abundance. And, yet, in the world's poorest places, they long for our affliction. Complicating matters further, we're constantly copulating, producing more mouths to burden already over-extended resources (and cry of want).

Modern man is not far removed early agricultural societies and, like our predecessors, we are subject to post-boom catastrophe. In fact, collapse is understood by anthropologists, sociologists, biologists and historians to be inevitable, a natural result of civilization's tendency to become increasingly complex and hierarchical. As Berman writes in 2000's "The Twilight of American Culture,"

"The whole statist configuration of hierarchy, specialization, and bureaucracy emerged fairly recently - about six thousand years ago - and has to be constantly reinforced and legitimized. It also requires an expanding material base and a constant mobilization of resources, and the trend is always toward higher levels of complexity. There is the processing of greater quantities of information and energy, the formation of larger settlements, increasing class differentiation and stratification, and the development of more complex technology. Collapse, which involves a progressive weakening of the political and administrative center, is the reversal of all this, and a recurrent feature of human societies...Thus, collapse is built into the process of civilization itself...[it] finally becomes an economizing process, the best adaptation under the circumstances."Berman, Kunstler, Taleb and Orlov believe that we are on the brink of such a collapse. Because I survey the same landscape, I don't begrudge the dystopians their opinions and predictions - perhaps we need the Cassandras to motivate us? - but I no longer feel that their pessimism suits me.

There are some of us who, though we may own shotguns, rifles or pistols, trust that we will not march on the houses of the wealthy. We accept the list of lamentations laid out by today's dystopian observers, yet remain realistic optimists. True, the comforts and excesses of the First World are endangered, and we doubtless face drastic social hemorrhaging following Berman's "economizing process," a necessary and natural correction, but, knowing these things, I still count myself among the Sisyphean hopeful.

The poet and essayist Christopher Cokinos wrote in a May/June 2007 issue of Orion that extinction should be accepted as an eventual given and, therefore, that civilization should be understood as a temporary exception. This perspective "nurtures sanity," he tells us. So, too, does an acceptance of social collapse and renewal. Acknowledging our species' precarious position is not defeatist; on the contrary, accepting the inevitable nourishes the individual's desire to contribute. Faced with an impossibly difficult prospect, only individual effort can sustain us. As Albert Camus concluded in "The Myth of Sisyphus," "The struggle itself is enough to fill a man's heart. One must imagine Sisyphus happy."

|

| Titian "Sisyphus" 1549 Oil on linen |

Similarly, a little knowledge of geo-politics will greatly distress most people. Alexander Pope's maxim has it that a little learning is a dangerous thing. True, and it can also be a depressing thing. Sheltered ignorance is relative bliss, but we can no longer afford that variety of comfort. We are instead obligated to witness the stresses, the horrors and the excesses of our world, and then work, in whatever way we can, to alleviate those ills, to replace the painful with the promising. Our choices may not always be right and there will be many "ups and downs," but the human spirit and species can not afford to succumb to apathy, complacency or Kunstler-like negativity.

In the preface to his book "Emerald City: An Environmental History of Seattle", Matthew Klingle writes, "Perhaps [Aldo Leopold was right], but one of the gifts of a historical education is knowing that some wounds heal in time or can be endured, and that we do not have to go it alone. History is no panacea, but thinking historically can help us live with the consequences of being imperfect creatures in an uncertain world." Cokinos shares Klingle's fatalistic, yet hopeful outlook.

"Too much grief for the world means less energy to help it along. [When] you find yourself free of the poisons that too much angst can cultivate, then something marvelous happens. You can sense how very old the planet is, how very old life and death are, and you can keep going on, you can keep doing the work you do in this universe, feeling despair when you feel despair, feeling - amazing - joy when you feel joy."

|

| President Barack Obama's January 2009 Inaugural Address |

"[There] are...indicators of crisis, subject to data and statistics. Less measurable but no less profound is a sapping of confidence across our land — a nagging fear that America's decline is inevitable, and that the next generation must lower its sights....We remain the most prosperous, powerful nation on Earth. Our workers are no less productive than when this crisis began. Our minds are no less inventive, our goods and services no less needed than they were last week or last month or last year. Our capacity remains undiminished. But our time of standing pat, of protecting narrow interests and putting off unpleasant decisions — that time has surely passed. Starting today, we must pick ourselves up, dust ourselves off, and begin again the work of remaking America....All this we can do. All this we will do....Now, there are some who question the scale of our ambitions — who suggest that our system cannot tolerate too many big plans. Their memories are short. For they have forgotten what this country has already done; what free men and women can achieve when imagination is joined to common purpose, and necessity to courage."Indeed, we are fortunate to live in a "now" when idealism and necessity intersect, in a now when I can trust in the happiness of wandering moons, can be grateful for my chance to work in this imperfect, wondrous world and can look forward to the continued expansion of the universe...and of our future.

3 comments:

I think you are right to point out the wider picture, instead of focusing on the doom-peddling that seems to have been particularly in vogue for the last few years.

I find the economic perspective useful, whenever I find myself shaking my head at something or other.

Annualised per capita world gdp growth:

0-1000 AD 0%;

1001-1820 AD 0.05%.

1821-1998 2.1%

The point being that it is a very recent event that the world as a whole has actually made any real, lasting development. At 50 years per generation, we are not even into a fifth cycle yet.

So resource consumption rate, and allocation are concerns, but I tend to be more positive with regards to societal change - with the hope that this will help sort out those resourcing concerns.

Peter:

Indeed, thanks for the numbers.

In recent decades, many environmental historians declared that the 21st century would be remembered as a century of global resource wars; it looks to be an accurate forecast (though the historians may have overlooked the role of religion in informing these resource wars, a tribal alignment likely to play a more prominent role than national identity).

I agree that societal change could sort out our global resourcing concerns, but fear that we're going to be entering some rough times before coming out the other end. If we move quickly - both with regard to governmental policy and individual effort - we can significantly reduce the global growing pains.

Will we? That remains to be seen.

All the best.

I think there definitely will be tough times, and I do think that there are some areas which need more attention ASAP.

Ownership and utilisation of water is one such area. This issue seems to me to need a very great deal more attention than it gets at the moment. We can do without quite a few things, but water is not one of them. I cannot see that it makes sense for water itself to be placed into private hands anyway (production and distribution being less clear cut).

Cheers.

Post a Comment