|

| Winter view of Platte Clove's Bridal Veil Falls; Catskills; NY |

“Many people have been killed after falling and sliding off the edge. Especially in areas where there are pine needles. Dangerous conditions exist in many locations. The number of deaths over the years is staggering. Be overly cautious when in this region, and do not take un-necessary risk.”I hesitated before deciding to investigate the unmarked spur of the Platte Clove Nature Preserve's Plattekill Falls Trail. Having recently read a bit about the geology and topography of the Catskill Escarpment, I knew that the preserve is located near the top of a deep ravine that tumbles suddenly down and eastward to meet the Hudson Valley (clove is the Dutch word for a mountain gorge). I’d also learned that each year a handful of foolhardy or unlucky hikers fall to their deaths on Platte Clove area trails. An online trail guide I’d browsed prior to the residency urged hikers to be “overly cautious.” Nevertheless, once I’d stepped off the main path and advanced a few steps down the spur, I was self-assured; I wouldn’t be one of 2012’s casualties. Prudent types like me don’t fall off cliffs.

- “Upper Platte Clove” page of Catskill Mountaineer website

Such confidence proves misguided at least as often as it is justified, but I didn’t consider that until, from a vantage point 100 yards along the trail spur, I looked down a section of the clove's headwall to another shelf of rock and soil perhaps 50 feet below. Beyond that ledge, my eyes fell far to sunlit treetops. The effect was vertiginous. Instinctively, I leaned away from the drop and squatted to lower my center of gravity. I shuffled low over the leaf litter and pine straw until I was sufficiently far from the brink to breathe easy. My bravado was rebuffed.

The quiet panic I experienced when I appreciated Platte Clove’s plunge for the first time was the result of our animal drive for self-preservation. Considered from a safe remove, however, I was stirred less by the prospect of my own mortality than by the fact of everything’s impermanence. The ravine is a dramatic reminder that all landscapes are in flux. The Catskill Escarpment pictured in Hudson River School paintings is recognizable today; the peaks, valleys, waterfalls, and outcroppings appear largely unchanged. But the scenery is not static. Imperceptibly, it is morphing.

That evening, back in the Platte Clove residency cabin, I reviewed the geological history of the Catskill Escarpment that I’d packed. During the Silurian period, about 400 million years ago, the region was a vast river delta and shallow, inland sea. Slowly, over the next 75 million years, mountains rose to the east. The sea’s limestone bedrock was in time covered by eroded material that washed down from the mountains, and this sediment eventually formed the shale and sandstone strata that the Catskill Mountains are known for today. 325 to 260 million years ago, the continents that we now call North America and Africa collided, and the region was thrust upward, creating dramatic mountain ranges and plateaus. As time and the elements acted on the new landform, the upper levels of the Catskill Escarpment plateau were eroded, creating stream basins, mountains, and valleys. Much more recently, between 100,000 and 300,000 years ago, Illinoian glaciers scoured the region, steepening its slopes and etching the deep trench that, following further erosion during the last Ice Age, became the ravine we now know as Platte Clove. Millions of years in the shaping, a measure of time comprehensible only in the abstract, Platte Clove continues to be carved and reworked by the creek that today flows through it to the Hudson.

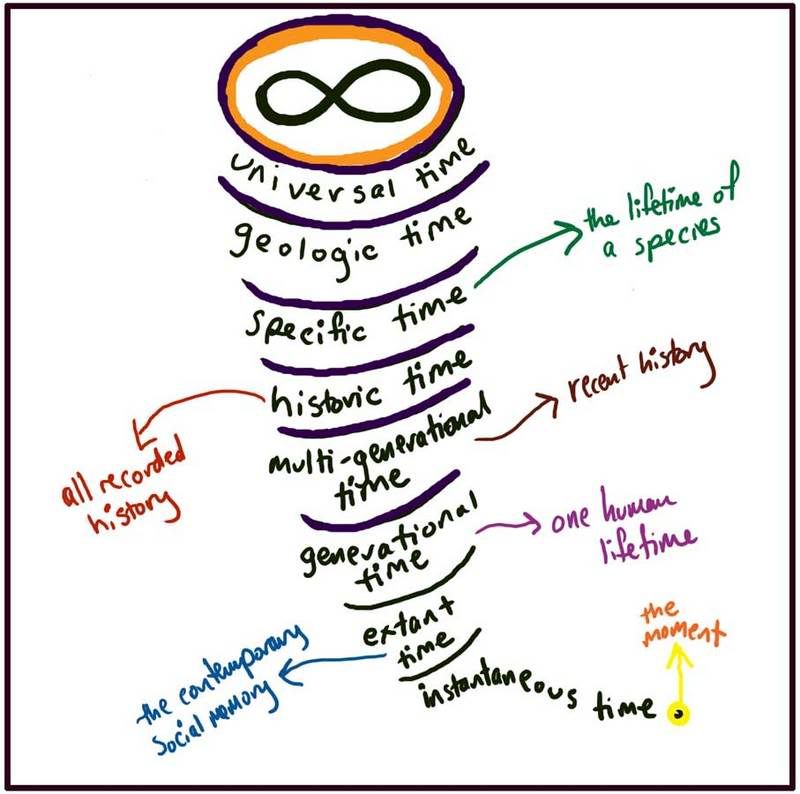

Because I’d just read a recent issue of Sierra, the Sierra Club’s magazine, on the flight east, I found myself contemplating the geological convulsions of the Catskills region alongside the message and tenor of Sierra’s articles. Compared to the tumultuous world of geology, the nature celebrated in the magazine’s pages seems like a peaceable kingdom. Certainly, the different time scales matter a great deal (one obviously occurs on the geologic level and we don't see the action, while Sierra’s perspective is limited to more recent and observable history – see Figure 1, an old diagram I created elucidating the multiple experiences of time), but a full appreciation of natural history and the outdoors requires a panoramic perspective. Focusing only on our moment and that which immediately preceded it is problematic. We must elude nostalgia’s withering grip; what came before is not necessarily better than what is or what will be. Easier said than done. Humans, like all successful animals, survive by prioritizing the clear and present over long range planning and imagination. Despite our tremendous capacity, we suffer from an evolved myopia. As the German philosopher Arthur Schopenhauer's wrote, "Every man takes the limits of his own field of vision for the limits of the world."

|

| Figure 1: My oh-so-professional diagram of different time scales |

Cognizant of that deficit, I’m often frustrated by the rhapsodic tone and wistfulness that predominates so much contemporary nature writing. The writers present only part of the picture. I'm no naysayer, mind you; every day, I rejoice in the beauty and wonder of the world, but I break with writers when they characterize nature as a wholly beneficent and fragile entity. Too many fail to free themselves from the legacy of Thoreau and Muir, 19th and early 20th century giants of the genre who, while a treat to read, proffer a romanticized account of nature.

Muir’s insistence that nature revitalizes the spirit, that it acts as a balm for civilization’s ails, is justified, but his essays provide an incomplete picture of why the outdoors are restorative. In his 1901 book, Our National Parks, he wrote,

"Camp out among the grasses and gentians of glacial meadows, in craggy garden nooks full of nature's darlings. Climb the mountains and get their good tidings, Nature's peace will flow into you as sunshine flows into trees. The winds will blow their own freshness into you and the storms their energy, while cares will drop off like autumn leaves."It’s lovely stuff, and it’s true that a certain kind of angst -- the “first world problem” variety – is forgotten when we’re exposed to the “freshness” and “energy” of meadows, mountains, forests, and storms. But several of my experiences on the trails around Platte Clove gave rise to anxieties of a different sort. Looking over a precipice or encountering a bear at close range, we are freed from the burdens of our domesticated lives because, for a moment or minutes, nothing matters except survival. My bank account balance, car engine trouble, the politics of family planning, geology…all of these concerns fall away. Muir celebrates one aspect of our encounter with nature (e.g., “darlings” and “good tidings”), but he ignores the existential dread that plays a vital role.

In 1913, Muir wrote "whales and elephants, dancing, humming gnats, and invisibly small mischievous microbes - all are warm with divine radium and must have lots of fun in them." There is much gentle beauty and grace in the natural world. We’re moved to reverie by the dreamy sweep of a turkey vulture on mountain thermals or the nervous dance of a swallowtail low across a meadow, but the bird is seeking carrion and the butterfly nectar and a mate. When contemplating nature, we shouldn't ignore the base drives that provide its backbone. Even those of us who believe we humans must hearken to the better angels of our nature ought to recognize that the lion doesn’t lie with the lamb. Moreover, most creatures, lambs included, are not one-dimensional. They are not either vicious or gentle; they are both. Muir's whales and elephants don't just dance. They fight, too. And, no matter how alluring the alliteration, microbes can't fairly be called mischievous; some are, however, accomplished killers. If we could ask Muir, I wonder if he’d agree that the "divine radium" is in all of creation, in the good, in the terrible, and in the ambivalent. I’m fairly confident he would not.

In Muir’s writing, ideology almost always trumps clear-headed reckoning. He advanced a Manichaean narrative with humanity cast as the bungling villain. This account isn't baseless. It's true, after all, that our widespread and assertive species impacts the world in often deleterious ways. It’s also the case that a great many ecosystems are imperiled because they're so delicately balanced. On the whole, though, nature is ambivalent and abiding, not beneficent and fragile.

It's our particular, temperate moment that is precarious. That being so, nature writers have an obligation to draw attention to the ways in which our species' recklessness and blossoming population burden the ecology of our day and thereby threaten the “limits of the world,” but by painting a picture of Eden, as many do, they tiptoe close to Disney's cloying and distorted vision of ecology, one macerated in syrupy sweetness and overlaid with Scar-Simba dualities.

|

View at trail edge alongside Platte Clove ravine; Platte Clove Nature Preserve; Catskills; NY; July 2012 |

It's no wonder, then, that I cheer Werner Herzog’s infamously bleak take on jungle ecosystems in the documentary, "Burden of Dreams." "We have to become humble,” Herzog said, “in front of this overwhelming misery, and overwhelming fornication, and overwhelming growth, and overwhelming lack of order.” The quotation serves as an antipode to the paeans produced by most poet naturalists, and Les Blank, the documentary's director, creates dynamic tension by punctuating Herzog's rant, which continues for minutes, with footage of ambling jungle beetles, tree frogs at rest, and leafcutter ants carrying their harvest. At what point does the base, violent striving of existence meet the profound beauty of being? Or are they one and the same?

I believe the latter to be true, and when we marry those two, apparently contradictory interpretations, Herzog's frightful and overwhelming nature and Muir's "divine harmony," the union is something like Soren Kierkegaard's "fear and trembling" or Schopenhauer's definition of the Sublime. Schopenhauer prescribed the Sublime as a remedy to his everyman limits. In his volume The World As Will and Representation (1818), Schopenhauer elucidated a scale of aesthetic experience. At one end of this spectrum, he described the “Feeling of Beauty” as “Light...reflected off a flower. (Pleasure from a mere perception of an object that cannot hurt [the] observer.)” At the other end of the spectrum, the philosopher positioned the “Full Feeling of Sublime” and the “Fullest Feeling of Sublime.” These categories are described, respectively, as “Overpowering turbulent Nature. (Pleasure from beholding very violent, destructive objects.),” and “Immensity of Universe's extent or duration. (Pleasure from knowledge of observer's nothingness and oneness with Nature.)”

Schopenhauer’s “Feeling of Beauty,” then, is akin to Muir’s carefree experience of nature, “warm” and “fun.” The “Fullest Feeling of Sublime,” however, is Kierkegaard’s “fear and trembling,” it is the ecstasy of one’s subsumption into being at large, a reduction or erasure of the self-conscious individual and a simultaneous opening of the individual to the wilderness within. In that moment, at last, nature is given its due, the lion and the lamb as one multifarious beast.

"This grand show is eternal," Muir wrote. Indeed, and how grand it is! As the Catskill Escarpment’s natural history illustrates, nature is a raging monarch, astonishing, awesome, and totally ambivalent. And here we are, in this particular moment, alive. Hopefully, we'll strike a balance that allows us to appreciate the view from the precipice, trembling and grateful.

|

| View into section of Platte Clove ravine; Catskills; NY |

Note: The sections of this essay dealing with Herzog and Schopenhauer are reworked versions of excerpts from past Hungry Hyaena pieces, "Review In Brief: Kota Ezawa at Haines Gallery" (February 2012) and "Christopher Saunders' 'Whitenoise'" (December 2009).

Photo credits: Winter Bridal Falls photo, Michael Stanislaw (date unknown); Photoshop illustration of time scales, Christopher Reiger, 2006; Platte Clove trail edge view, Christopher Reiger, 2012; Platte Clove ravine photo ripped from CatskillSearch.com

No comments:

Post a Comment