|

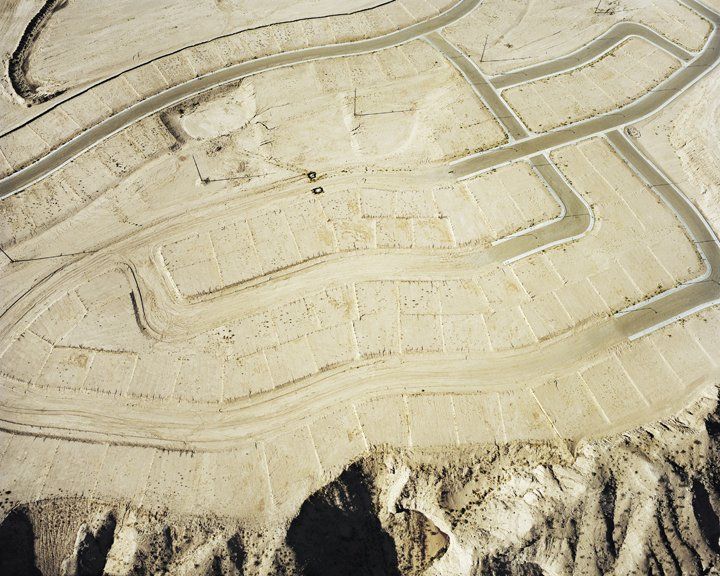

| Michael Light "Lake Las Vegas 2010-2012 20. 'Casa Palermo' Lake Las Vegas Homes Looking Southwest, Henderson, Nevada" 2010 Pigment print mounted on aluminum 40 x 50 inches Edition of 5 |

I recently visited Hosfelt Gallery's impressive new space, currently home to "Private Frontiers," a two person show featuring works by Brooklyn-based painter Chris Ballantyne and San Francisco-based photographer Michael Light. According to the press release, the two artists "have been in dialogue for the past year to develop work that examines the human urge to stake territory and its more absurd manifestations on the American landscape." Whatever the specifics of the artists' conversation, Ballantyne's paintings are a terrific compliment to Light's large-format aerial photographs. Exhibited on their own in the expansive Hosfelt loft, Ballantyne's colorful and occasionally whimsical works would risk being swallowed up as bittersweet morsels. Hanging alongside Light's grand photographs, though, Ballantyne's modestly-sized pictures comport themselves especially well; their affability and humor endure, but undercurrents of earnestness and melancholy, too easily missed if exhibited on their own in so airy a space, are amply felt.

|

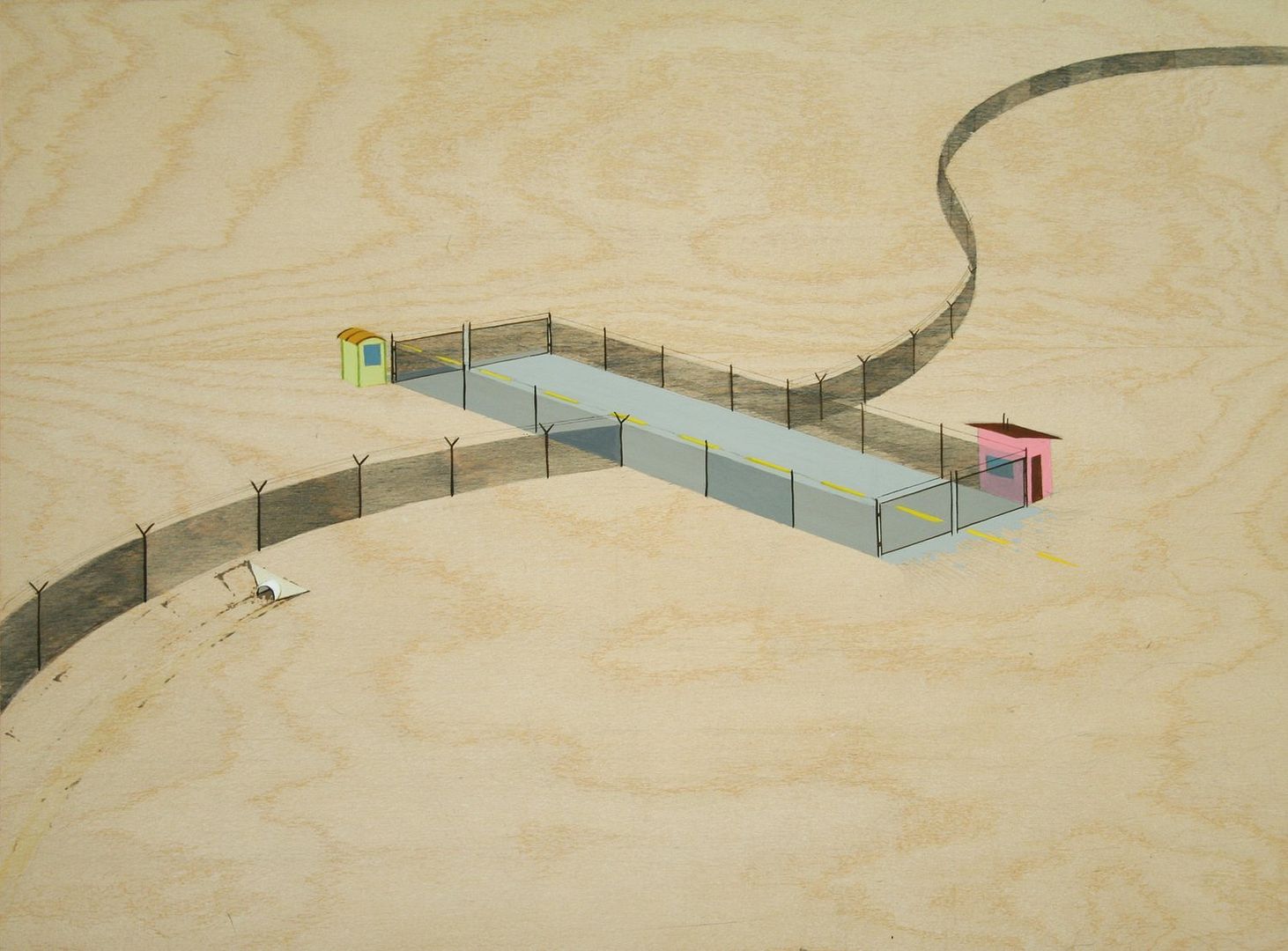

| Chris Ballantyne "Not a Thru Street" 2011 Acrylic on panel 12 x 16 inches |

Likewise, in the company of Ballantyne's works, the wry humor and conceptual nuance of Light's photographs is made more perceptible. From Light's perch (a lightweight, high-winged, and doorless airplane that he pilots), the interventions of mankind on the landscape appear at once less and more offensive, a result of the shift in perspective and scale. These are complicated, awesome pictures, imposing, yet understated enough to invite a multiplicity of readings.

|

| Michael Light "Lake Las Vegas 2010-2012 14. Future Homesites of 'The Falls' at Lake Las Vegas, Henderson, Nevada" 2011 Pigment print mounted on aluminum 40 x 50 inches Edition of 5 |

The terraced Nevada desert landscape pictured in "Lake Las Vegas 2010-2012 14. Future Homesites of 'The Falls' at Lake Las Vegas, Henderson, Nevada" might be mistaken for an ancient, ziggurat-like structure, excavated by archeologists. It could also be an ambitious new Earthwork undertaken by the likes of Michael Heizer. In actuality, as the picture's title reveals, it is an unfinished residential development project. Knowing this, we're liable to shrink from the photograph, filled with righteous indignation about our species' profligacy and environmental thoughtlessness. Even as we do so, it's worth noting that we'd almost certainly react differently were we looking at a photo of an archeological site or contemporary Earthwork heroics.

In "Future 'Highland Vista Age-Qualified Master Planned Community' Homes by RFMS Looking Southeast, Mesquite, Nevada; 2010," we look down on unfinished roads to nowhere, a stark hieryglyph on the desert surface. The photograph is as aesthetically compelling as its subject is ludicrous. In another of Light's pictures, we see an absurd mirage, a relatively verdant luxury development abutting sun-faded desert mountains. The developers named this gated luxury living community "Casa Palermo," after the Sicilian seaside city. We rightly shake our heads at the environmental irresponsibility (and lugubrious name) of such a venture, but when we contemplate "Casa Palermo" in the context of geologic time, considering the action of tectonics and climate over millennia, we might, for a moment, view the gated community as representative of our species' tenuous prospect.

Indeed, as I wrote of Light's work in 2007, the photographs "encourage us to question conventional notions of natural and artificial, and also to consider these environments with respect to the full sweep of time and scale." Spend enough time in a gallery filled with Light's photographs and book works, and the pictured developments and mines will begin to call to mind tissue slices or cell cross-sections. The forms and processes never seem benign, and sometimes -- too often -- appear malignant, but they highlight the vain futility of mere value judgments. Light's work reminds us that it's too easy (even dangerous) to label humanity a cancer and throw up our hands; the responsible thing is to regulate -- to direct and control -- the ontogenesis, and to understand that it is, itself, a natural phenomenon.

|

| Michael Light "Edge of the Black Thunder Coal Mine, 9% of American Supply, Wright, WY" 2007 Pigment print mounted on aluminum 40 x 50 inches Edition of 5 |

|

| Chris Ballantyne "Pass Through" 2011 Acrylic on panel 12 x 16 inches |

2 comments:

Coming from a stance in which the idea of "stewardship" in one form or another is deeply embedded, it's easy to accept the closing argument of the necessity "to regulate." I believe the counter to this would be one of "the earth is here for us to use as we please" - one that's (probably knowingly) short-sighted in terms of human & environmental preservation but instead focused on something entirely "else."

Even some agreement about the idea of "stewardship" and consequent "regulation" of course opens the question of who does the regulating, and how it's done. In this particular time and place, the word "regulate" implies "government," which in turn shapes any conversation or debate into fairly familiar stances & bromides. Ballantyne's paintings seem to echo this "debate."

@ mattf:

Thanks for the thoughtful comment.

I recently read a terrifically informative summary of the evolution of Aldo Leopold's economic and ecological thinking ("Aldo Leopold: Reconciling Ecology & Economics," by Qi Feng Lin, a publication of the Center for Humans and Nature).

Leopold is considered a grandfather of the conservation movement, and he's a personal hero, but he wrestled with the question you raise -- WHO should do the regulating? This question would grow to prominence in the decades following Leopold's early death. From the article, "The problem of reconciling personal freedom with the need to coordinate human action on the land, which is usually thought to be achieved through coercive state-directed efforts, would become a recurring theme in environmental discourse during the environmental movement of the 1960s and 1970s - and up to the present."

For his part, Leopold called for a transformation of our ethical approach, his "land ethic," which insisted upon individual stewardship of one's property (to achieve a healthy balance of the economic and ecological motivations/ends). As your first paragraph shows, that ethic still has yet to materialize on a grand scale.

Leopold initially argued for the place of state and federal regulation/involvement, but, in later years, came to regard that skeptically (even as wrongheaded). Lin writes, "Leopold's emphasis on personal stewardship on the land could be seen as the foundation of an alternative to both unbridled and unprincipled economic capitalism and a socialist economy with a paternalistic government presence." That middle road sounds like the best path, and I trend "Leopoldian," but see an important place for incentive programs at the state and federal level since the widespread "land ethic" has not materialized. With respect to regulation, it seems that rewarding "good" behavior is the best kind of regulation (i.e., conservation easement programs and the like).

Post a Comment