As regular readers know, I've been writing profiles of emerging artists for the now defunct (or perhaps hibernating) ezine, Scrawled. The piece that follows, an essay about Deborah Simon's paintings, was scheduled to run in Scrawled's June 2006 issue, but the publication never materialized.

+++++

Deborah Simon

"Memento mori: Ocelot and ocelot skeleton"

2001

Oil on wood

36 x 68 inches

I would take a hamster or a hedgehog or a mole

And place him in a theater seat one evening

And, bringing my ear close to his humid snout,

Would listen to what he says about the spotlights,

Sounds of the music, and movements of the dance.”

-Czeslaw Milosz

Reading Milosz's lovely poem, I picture the poet hunched over, head cocked so as to position his ear close to a confused, sausage-shaped insectivore. The man concentrates on the light, rapid breathing and the occasional scritch of the mole’s long claws on the seat’s velvet lining. The little burrower tentatively senses its surroundings but remains totally unprepared – and unable - to describe the auditorium. Here, in so vast a space, it is terrified. It would prefer to be elsewhere, digging in substrate for an earthworm or a tasty grub.

But most readers of the above poem will imagine a very different mole, a chatty, colorful fellow wearing soda bottle spectacles who sits upright in the theater seat, his hands just achieving the armrests. In honor of his famous Disney relative, we might call this cartoon caricature Mickey Mole.

The anthropomorphized mole is the more popular of the two. Unfortunately, the Mickey Mole rendering undermines Milosz’s point. The poem is moving only if the poet relates to the animal as exactly that, an animal. He must overcome the temptation to project human qualities onto the creature. Only diligent observation of the “real” organism, rather than the caricature, will equip the poet “to tell what the world is for” him. Careful “listening” to the displaced animal on the theater seat reminds the poet that he, too, is animal, representative of just one species among many. Thus, the “essential conditions of life”(1) are recognized: human nature is nature.

But today we live in an age of mediated interaction. It is increasingly difficult to perceive a mole as a mole. The world’s rural population is dwindling and the urban experience of wilderness and wildlife revolves around television, animated features, photographs published in National Geographic, and the bars and reinforced plexi-glass of zoo enclosures. In his 1980 essay, “Why Look At Animals?,” John Berger critiqued this contemporary relationship (or lack thereof), focusing particularly on the “imperfectly-met gaze.” Just as servants were once prohibited from making eye contact with aristocratic employers, so too is meaningful ocular exchange between animal and human avoided. Animals are not aware of this prohibition. As a result, it is the supposedly superior party that must ignore, pillory or avoid their gaze. Berger argues that humans possess animals by visual means; we look at them, but do not allow the animal to look back “across ignorance and fear.” The human peering through a viewfinder objectifies the animal, reducing it to an icon.(2)

Zoos make this objectification more explicit; visitors feel superior to the caged creatures, often literally looking down on them. In both examples, the scalae naturae is made manifest; man is granted dominion over the beasts. Berger writes, “The fact that [the animals] can observe us has lost all significance. They are the objects of our ever-extending knowledge. What we know about them is an index of our power, and thus an index of what separates us from them.”(3)

But what of painting? Animals are central to the work of innumerable contemporary artists(4), but the majority of these paintings betray an indifference to natural history and the corporeal nature of the animal represented. The otters, bears and tigers that populate these pictures are crudely rendered in the favored style of the day – broad, slapdash brush strokes and bold, electric color – and they are removed from their natural habitat or, if not, their habitat is turned into a world of flat, cartoon significance. These are not animals, but shallow proxies more closely related to stuffed toys and Saturday morning cartoons. As such, they are given license to look back at the viewer; their fiction has made them impotent.

Wildlife art, a more "realistic" - if sometimes naïve and much maligned - genre, is as popular today as it was a century ago. Susan Orlean wrote that to be good at taxidermy you “have to be a little bit of a zoology nerd” and “you have to love animals.”(5) The same requisites could be applied to wildlife art. The best artists of this kind celebrate the animal through naturalistic depiction.(6) Though technical virtuosity and compositional sensibility varies greatly, all wildlife painting is in the business of illustrating reality and, in doing so, of honoring the animal pictured. Curiously, very little wildlife art depicts an animal (or animals) making eye contact with the viewer.(7) As with television wildlife documentary and magazine photographs, the gaze remains one-sided; even in admiration, man possesses the animal.

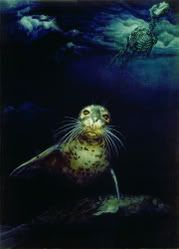

Deborah Simon

"Phoca vitulina: Harbor seals under pack ice"

2003

Oil on wood

66 x 48 inches

Deborah Simon claims she “has no interest in traditional wildlife painting.” To be sure, her paintings and sculptures can not be fairly classified as wildlife art, for reasons I’ll explain in a moment, but she does share the desire of wildlife artists to present the animal as dignified and real. The animals she paints are not anthropomorphized; they exist on their own terms and the viewer has no choice but to relate to them as such. Simon’s work is distinguished, however, by the met gaze, the completed ocular exchange John Berger eulogized in “Why Look At Animals?”.

In Simon's Memento Mori series, animals either look directly at the viewer, as in “Enhydra lutris: Sea Otter Raft” and “Phoca vitulina: Harbor Seals Under Pack Ice,” or confront their own, skeletal visage, as in “Memento mori: Ocelot and ocelot skeleton” In both cases, the potency of the visual exchange is restored. Gone is "Mr. Otter," the cute and cuddly companion. Present, instead, is the powerful and curious Enhydra lutris, consumer of crabs, fish and molluscs. To lock eyes with this sea otter is to possess the animal, but also to be possessed. This two-way gaze allows for the erasure of both individual and special (as in "species") autonomy. Furthermore, the skeletal apparitions that surround the painted otter are reminders of its mortality and, in turn, of our own. The exchange provides a one-two punch. “You, too, are animal," the paintings say. "You, like me, will die.”

Deborah Simon

"Enhydra lutris: Sea Otter Raft"

2002

Oil on wood

35 x 48 inches

Were we to actually have this encounter with a sea otter, in the cold, coastal waters of the northern Pacific, it would be brief. For a moment we lock eyes with the animal and stare transfixed. Then, abruptly, the otter returns his attention to devouring the abalone grasped in his dexterous paws. Because the eye contact is fleeting, its significance is more likely recognized by those of us who already question the scalae naturae. Simon’s painting, by contrast, grants the viewer no release; both the otter and its skeletal counterparts stare us down, unrelentingly. (“One of us. One of us.") Even Berger’s urbanite, that lover of Disney, is left with no recourse; he must confront the fragility of self and see in himself the “other.” What Simon’s work accomplishes, then, is rare and wonderful. In celebrating other species, she humanizes our own.

life, the animals approach man

to be mystified.”

-from “3 Poems,” by Les Murray

Deborah Simon

Memento Mori: Red Squirrel and Skeleton"

2001

Oil on wood

31 x 23 inches

+++++

(1) John Dewey, “The Live Creature,” Art As Experience, 1934

(2) “That’s why a couple of weeks out in Nature doesn’t make it anymore…you will virtualize everything you encounter anyway, all by yourself. You won’t see wolves, you’ll see ‘wolves.’ You’ll be murmuring to yourself, at some level, ‘Wow, look, a real wolf, not in a cage, not on TV, I can’t believe it.’ That’s right, you can’t. Natural things have become their own icons.”

-Thomas de Zengotita, “The Numbing of the American Mind,” Harper’s Magazine, April 2002

(3) John Berger, “Why Look At Animals?”, About Looking, 1980

(4) Contemporary artworks concerned with ecology, natural history, and zoology are, more often than not, American in origin and, if not, they are almost always Western. There are many different arguments as to why this is so, but the answer, I feel, is bound to the unique relationship early Americans – and I’m thinking of both Native Americans and the European settlers – had with the expansive wilderness around them. The concept of “wilderness” is borne of Romanticism and colonialism and, what's more, is limited to those countries/regions with vast, undeveloped tracts: North America, Australia, Africa, eastern Russia. As much as I embrace it myself, wilderness is a Romantic, fraught ideal, one equally capable of protecting and harming the species that live away from human settlement. Increasingly, this Romantic idealization of the "wild" is spreading into the East, via China and Indonesia, but the concept there remains an introduced one.

(5) Susan Orlean, “Lifelike”, The New Yorker

(6) Walton Ford, Alexis Rockman and their ilk are not of this camp, although some art world cognoscenti may disagree. This isn't to say that Ford and Rockman aren't deeply invested in their subject matter (wildlife, natural history, ecology), but rather that their work is as grounded in satire and critique as it is in celebration and admiration.

(7) When eye contact is made, the artist is often painting what I'll call the “dramatic encounter.” For example, an angry bull African elephant (Loxodonta africana) charging the viewer or a Great horned owl (Bubo virginianus) interrupted mid-meal.

2 comments:

payforbuzz.com

Product placement in blogs!

Generate buzz for your product!

Fascinating - thank you.

Post a Comment