Because I reject the notion of a creative, interventionist God, I can not explain away mystery by assigning works to His hand, but hard science doesn't always satisfy either, at least not in any immediate way. The surgeon and bioethicist Sherwin Nuland says that wonder "is something I share with people of deep faith." He continues, "They wonder at the universe that God has created, and I wonder at the universe that nature has created. But this...sense of awe that motivates the faithful, motivates me. And when I say motivates, it provides an energy for seeking. Just as the faithful will always say, ‘We are seeking,’ I am seeking."(1) Perhaps, then, it is enough to say that my dike experience was the product of wonder, but the words of Ralph Waldo Emerson and Walt Whitman provide my experience with an even more poetic, transcendental framing. Emerson characterizes his marriage to the unconscious as a physical transformation: "Standing on the bare ground,-my head bathed by the blithe air and uplifted into infinite space, all mean egotism vanishes. I become a transparent eyeball; I am nothing; I see all; the currents of the Universal being circulate through me." Whitman also writes of universal tissue, "of the threads that connect the stars, and of wombs and of the father-stuff."

A true rationalist might dismiss Emerson and Whitman as ridiculous transcendentalists, but I departed the Shore just before New Year's, feeling closer to the indefinite whole, the Everything, than ever before. I felt as though I had stumbled ass-backwards into faith; I was calm, satisfied and humbled.

After only a few weeks in New York, fond of it though I am, I felt weary and anxious. The frivolous stress of day-to-day city life made me irritable; I stewed, grumbled, and generally felt out of whack. Close friends mistook my deportment for depression, but I explained to them that I was merely frustrated by city living.

Fortunately, art-making continued to go well, and I found some solace in the long hours spent pondering how best to position myself, geographically speaking, so that I could paint and write without suffering from NYC burn out. I wrote the post "Inside Out (And Upside Down)" in an attempt to work through the issue. I objected to so much in the course of that essay - Art World social demands, consumerism, the cancerous nature of ambition - that one commenter responded, "I...think you’ll be more satisfied once you finally leave the pavement for the woods. Also, why are you tying yourself in knots trying to please an art system whose goals are in direct opposition to your own? I say better to forge your own path." Fair enough. Though I may not yet know where the next five years will take me, I will almost certainly leave New York and, this being the case, I find a great deal of inspiration and hope in the art and life of the contemporary painter and photographer Tom Uttech.

I've been meaning to complete the post that follows for many months, ever since Uttech's Fall 2006 solo exhibition here in New York. As it turns out, I'm glad that the writing took me so long. Revisiting Uttech's paintings and interviews as I edited the piece, I again felt calm, confident that, pending the right choices, I will find what Uttech calls "the sweet spot."

Since 1987, Uttech has lived on a sixty-acre property not far north of Milwaukee, Wisconsin, a city he was "stuck in for a few years." His studio is inside an old barn. As Barbara Joose writes in her 2001 interview with Uttech, "Most artists would have called this place a studio because this is the place where Tom paints. But he doesn't. He calls it a barn...Tom had intended the other room [of the barn] to be a winter studio, but it became a sorting area and storehouse for harvested prairie seeds." Uttech spends the better part of each day outdoors, "planting, harvesting seeds...prairie projects. Or I do birding in the spring...I gradually make my way home and then begin to paint. I paint till my face falls into the palette." In fact, he says his prairie restoration side project has almost developed into a business unto itself. "I collect seeds, grow prairie plants for some of the nurseries...I'd like to do this for a living."(2)

But he doesn't, at least not yet, and the "sweet spot" he speaks of is the kind of life I hope to one day find, even if after years of art school (as both student and, then, teacher) and some critical attention - his work was included in the both the 1975 and 1977 Whitney Biennials - Uttech has little to say about the art world. "When art is about itself, it isn't any good. Those in the art world keep looking at each other....When you begin to seek that as your goal, your art becomes anemic...Dull, listless. Derivative. Vacant." His negative reaction to the contemporary art milieu led him to stop making work altogether. (He describes this decision bluntly, "Just screw it. I'm not an artist. If this is what I have to do to be an artist, I'm not going to be [one].")

Fortunately for the rest of us, his hiatus didn't last too long. Uttech is now in his mid-sixties and his career is established and healthy. All the same, he says, "I've been marginalized by the art world. I'm probably lucky that I've been marginalized. I am lucky - in a lot of ways. I sell everything I do. But I'll never be in the Museum of Modern Art, or a trendy place. I'm not one of the people who are discussed. I'm invisible."(3) Judging by the flurry of gallery shows, museum retrospectives and reviews in the last five years, it seems Uttech isn't so invisible anymore. I'm pleased by the attention his work is receiving and happy that there are exceptions to the rule for younger artists to look up to, particularly when the exceptions are dealing with essential subject matter.

Tom Uttech

"Nin Baba Madaga"

2005

Oil on rag board

16 1/4 x 18 inches

Courtesy Alexandre Gallery

"I am no more lonely than a single mullein or dandelion in a pasture, or a bean leaf, or sorrel, or a horse-fly, or a bumblebee. I am no more lonely than the Mill Brook, or a weathercock, or the north star, or the south wind, or an April shower, or a January thaw, or the first spider in a new house."5:05 PM, and the rain was heavy and cold. Pedestrians huddled under awnings or in the doorways of their office buildings, reluctant to brave the downpour. My umbrella proved laughably inadequate; the wind whipped water horizontal, soaking my arms and backpack. The weather was fitting, though. In 2003, on a similarly stormy afternoon, I stumbled into the ample lobby of 41 East 57th Street to escape the elements. I noticed several galleries listed on the building's directory and decided to look at some art while the rain continued. One of the artists exhibiting upstairs, at the Alexandre Gallery, was Tom Uttech, a name then unfamiliar to me. Now, three years later, in similarly inclement weather, I was heading back to the mid-town building to check out Uttech's latest efforts.

- Henry David Thoreau, (1817-1862)

"I kept seeing things in the landscape that would create a very strong feeling, like an aching, a yearning or longing for something, but I didn't know what. But what I think I'm yearning for is to be that thing, to stop being myself in this body and stop being aware of my life and just be that thing. That's why I paint the stuff."

-Tom Uttech

Visiting as many shows as I do, I often see artwork that is relevant to my own. The list of my creative cousins grows longer each year; I'm forever being introduced to "new" artists, both living and deceased. Yet it's rare that I come across a work, or body of work, that I might consider a sibling. Tom Uttech's paintings qualify. I feel elated in their presence, reminded of what it is that impels me to create. It's an intensely gratifying experience.

Reading interviews with the artist, or essays about him, I sense a kindred spirit. Uttech bemoans the contemporary disconnect between man and Nature, while still acknowledging the geologic scale. "People have never been less connected to the natural world...It's bleak. (4) [But Nature] doesn't care if it's a gravel pit or a pecan forest. It's all wonderful for nature, but it's not going to be wonderful for us...Nature doesn't give a shit. Life goes on, with or without us.(5)"

When Uttech extols the plenitude of marshes, he describes them as "an absolute cacophony of noise and activity." Until I read this quote in Lucy Lippard's essay profile of the artist, "Magnetic North," I hadn't come across another who had absorbed (and presumably unconsciously co-opted, as creative people are apt to do) Bern Keating's observation that "poets who know no better rhapsodize about the peace of nature, but a well populated marsh is a cacophony." I was young when I first read the Keating line, young enough that I didn't know what the word cacophony meant, but I dutifully looked it up and the quotation has been a favorite of mine since, even appearing as one of my high school senior quotations.

But naturalist sentiments are by no means extraordinary; they are shared by most environmentalists, wildlife biologists, and outdoor enthusiasts. It is unusual, however, for an individual of this ilk to portray or celebrate a supernatural Nature, one shrouded in magic and mystery, informed as much by the shadows of our interior world as by external observation. More often than not, we "nature guys" produce realistic wildlife paintings or photographic documentary. As a result, I've sometimes felt that I might be betraying my calling, that I, too, should paint the natural world as we "know" it (or, more valuable still, funnel my energy and resources into conservation and sustainable development projects). But when I've dabbled in traditional wildlife painting, I've been dissatisfied. I'm compelled to portray a totemic Nature, a world of symbol and ecstatic interpretation that celebrates the ether as much as it does the tangible or the quantifiable. I'm just now learning how this might be done. Clearly, Uttech already knows well.

Tom Uttech

"Nin Bapinendam"

2006

Oil on rag board

15 1/2 x 19 1/4 inches

Courtesy Alexandre Gallery

The world Uttech depicts is comprised of signs. Every animal, fallen limb or creeping mist is a stand-in for itself, or for the greater self. A Uttech black bear is not just a black bear, but the very manifestation of Bear. The animal is abstracted and ennobled. This totemic understanding of Nature is appropriate in a time when human contact with the "real thing" - wilderness, the circle of life, or whatever you call it - is increasingly mediated, but no less vital. Adrift as we are in the culture of spectacle, distraction and disposability, Uttech's pictures offer the contemporary viewer an opportunity for grounding and surrogate experience; they satisfy our deeply rooted need for the woods and the sky, for a broad, mythic conception of existence, but only if we're willing to open ourselves to it.

In many of Uttech's paintings, animals stand erect and look out at the viewer. In "Assandjigon," for example, four bears, having risen to their hind legs, stare from the edge of a spruce forest. They are rigid and perfectly still, their dark eyes fixed on us. I discussed John Berger's "imperfectly-met gaze" argument in an essay on the work of painter and sculptor, Deborah Simon, but it bears mentioning again. Berger asserts that humanity possesses other species by visual means, objectifying them to allow us the illusion of dominion. The animals that populate paintings by Uttech and Simon, however, return our gaze. We possess the animal, but they also possess us. "This two-way gaze," I wrote of Simon's work, "allows for the erasure of both individual and special (as in 'species') autonomy." Therefore, the viewer must accept her part in the greater whole. Along these lines, Lippard writes, "Uttech's bears, deer, moose, or wolves fearlessly return our gaze, holding their place with uncanny dignity, defying humanity to imagine that it can dominate nature." Uttech himself puts it more bluntly. "They're standing up and saying 'take a look at me. I'm watching you and not just being observed.'"

Tom Uttech

"Nind Ogwissinam"

2006

Oil on linen

43 x 47 inches

Courtesy Alexandre Gallery

Lippard says Uttech is "almost desperately combating humanity's increasing distance from nature." But in rendering a totemic Nature, even one in which the animals engage the viewer, Uttech is not choosing an aggressive path; his paintings are subtle and risk being overlooked by the skeptical and impatient eye of the contemporary art world initiate. The world of magic and metaphysical significance that he celebrates is attached to ancient experience, but by building his pictures of reflections and silhouettes, Uttech leaves room for the viewer to dismiss the vitality as mere signage. Whereas Simon's paintings force the viewer to return the gaze of the animal subject, viewers of Uttech's paintings might elect to ignore the bears altogether. When Uttech discusses his outings in northern Wisconsin, he describes wildlife as being "present without being visible. But if you spend a lot of time paying a lot of attention - if you start to act like a hunter or think like a bird watcher - you get around that invisibility. And at a number of magic times you actually run into things." His paintings call for this same heightened awareness and, because most contemporary viewers will not "act like a hunter or think like a bird watcher," the bear's gaze will likely go unmet, the magic unfelt. This is less a critique of Uttech's work than a testament to how much we, as animals, have betrayed our biology and spirit.

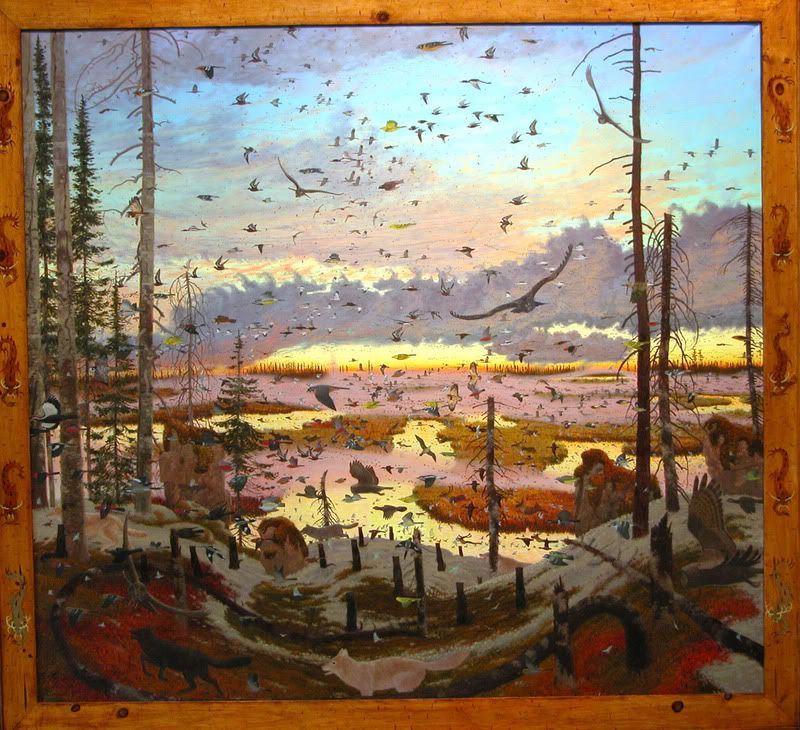

Tom Uttech

"Nin Maminawendam"

2006

Oil on linen

103 x 122 1/2 inches

Courtesy Alexandre Gallery

Uttech's symbolism extends to his handmade frames, onto which he carves, paints or burns "primitive" images of insects, animals, tracks, plants or strange hybrid creatures he calls "tricksters." The "tricksters" appear as though they're lifted from a Hieronymus Bosch tableaux, but Uttech explains that they are loosely based on the Ojibwe character Maymayguishi, or the Wendigo, a malevolent, cannibalistic spirit responsible for, among other things, whisking away that which goes missing. The artist feels that the frame imagery provides further context for the painting, one of "greater magic."

There is another sort of magic present in Uttech's work, however, one that appeals to us in a visceral way. Our evolution shaped us to lust for abundance. Although a surplus of any one species is rarely a net positive for an ecosystem, we associate large numbers of birds, mammals or fish with fecundity and prosperity. When European settlers first arrived in the New World, they marveled at the miraculous bounty available to them. In letters sent back to loved ones and political figures in Europe, the settlers wrote of alewives so tightly packed in rivers that a man could walk across on their backs without getting wet; they also detailed flights of waterfowl so thick that one shotgun blast would fell forty birds and a beaver population healthy enough to provide coats for thousands of sophisticated European ladies. In other words, they were ecstatic salesmen. Even today, when many humans no longer directly equate an animal with commodity - if only because that bloody reality is hidden from the majority view in industrialized nations - we respond to sheer quantity.

Many of Uttech's larger canvases are teeming with life. His skies are crowded with birds and his forest floors and banks are populated by assorted mammals, some hidden, some in obvious view. In the presence of these pictures, one can't help but feel awed. It isn't the paint itself that does this - Uttech is not much concerned with surface or handling, instead choosing to focus on composition, color and narrative - but rather the spectacle he depicts. Because the animals usually move in one direction, reviewers often wonder what has caused the disturbance, what it is that the animals are fleeing. Given our tumultuous times, the assumption of alarm is sensible, but I feel, too, as though the wolves, kestrels, pileated woodpeckers and lynx are propelled by blind exuberance. They aren't necessarily escaping an enemy; they might also be inviting us to discard the Self and run with them into the immensity of the cosmos.

Tom Uttech

"Nin Minodashimin"

2006

Oil on linen

36 1/2 x 38 1/2 inches

Courtesy Alexandre Gallery

Uttech titles each of his paintings using Ojibwe words. He feels these names locate the paintings by honoring their inspiration, the north woods of Wisconsin and southern Ontario. When the artist first began using the language, he had no idea what the words meant; he choose the titles based on "beautiful looking and unpronounceable" map names. He has since studied Ojibwe, but despite what he characterizes as a "complete immersion," Uttech confesses that he has only a very general comprehension of the vocabulary and no appreciation of the grammar. Necessarily, then, his titles make little sense to native speakers. There are some critics of the artist who feel his decision to use a bastardized Ojibwe is an insult to the Indians, a trite nod to authenticity, or both. Their charges aren't unfounded, but experiencing Uttech's work I feel the artist has as much claim to the words as do those who know it as a mother tongue.

Uttech has inherited, if you will, the Ojibwe language just as he inherited their reverence for these woodlands and marshes. He began visiting the region in 1967 and, on his first trip, recognized that the landscape called to his primal nature. "This [is] where my spirit resides," he says; the paintings depict the north woods "because that is what I am." In "Magnetic North," Lippard writes, "There in the woods and wetlands [Uttech] learned to be alone, to deal with blackflies and thunderstorms, to 'walk like a hunter,' and to feel his way confidently through the woods in the dark, every sense quivering - a metaphor for finding his way through art by immersing himself in nature." Uttech's deep connection to the landscape, I believe, makes him a surrogate son, and therefore his borrowing of the region's mostly forgotten language can be forgiven. He may yet be a clumsy child, something of an interloper, but he is fully present in each moment. That's more than can be said for most of us, and reason enough for the rest of us to look at his pictures thoughtfully. Approach Uttech's paintings as John Dewey's "live animal" and you will find that, as Uttech puts it, "what's in the world, it's magic beyond belief."

Image credits: All images supplied by Alexandre Gallery

(1) Nuland quote from interview with Krista Tippett on NPR program, Speaking Of Faith, January 18, 2007

(2) Artist quote from: Lucy Lippard, "Magnetic North," Milwaukee Art Museum, 2004

(3) Artist quotes in paragraph all from: Barbara Joose, "Tom Uttech: Retreat To Reality," Porcupine Magazine 5, No. 2 (2001)

(4) Artist quote from: Joose

(5) Artist quote from: James Auer, "Wizard of the Wild: State artist explores mysticism, magic of nature," Milwaukee Journal Sentinel, July 10, 2004

(6) Artist quote from: James Auer, "It's All Natural for This Artist," Milwaukee Journal Sentinel, March 10, 2002

6 comments:

Chris,

Your essay about Tom Uttech's paintings is one of the best I have read in quite a while. I am not so sure where the essay stops and you put up one of Tom's paintings on display, but I really liked the continual narrative. They took me back to a spot to Kerala (where I spent my summer holidays) amongst the paddy fields and canals of Alleppey. Very few people take the time to lovingly describe and write about nature and you are one of a few.

That said, I detect traces of you leaning towards a more abstract representation of nature forms here - especially when you write "But I've dabbled in traditional wildlife painting and found myself immensely dissatisfied. I'm compelled to paint a totemic Nature, a world of symbol and ecstatic interpretation that celebrates the ether…" and when you say "they might also be inviting us to discard the Self and run with them into the immensity of the cosmos. One day, I'll do exactly that" ...

I look forward to seeing more of the paintings that you may be working on this year other than the two that have been publicly posted thus far (given influences like Tom on your soul).

I am planning on going to the Alexandre Gallery next week and I will be happy even if I get a fraction of the enjoyment that you found there.

Thank you once again on writing this moving essay that showed me a deeper meaning for Tom’s works….

This essay is beautiful. Both sad and wonderful. I recently found your blog and I am very much amazed that it exsists. I relate so much to the way you consider the natural world. Just wanted to say thanks for exsisting.

www.mollyschafer.com

Sushil:

I read some of the links you provide. I agree with most of your points, although - and I'm sure you realize this - your prescription for our woes amounts to a complete restructuring of society, one which would necessiate revolution and the destruction of all technological interface. Suddenly it seems as though the Uni-Bomber Manifesto is a handbook. Please don't overlook the fact that everything is connected, and that to wage war on modern man is to wage war on Nature at large. Complexity is a bitch. The healing begins best at the local level. Just do what you can where you can...and can (pardon the bad wordplay) the crusade.

Sunil:

Thanks. I've been enjoying some of your posts, too.

My paintings won't be getting too abstract anytime soon. At least, I doubt it. The abstraction occurs in the looking. The artist need only provide a few clues.

Molly:

That's very nice to hear. Thank you.

Hmmm...I've come across your blog twice now so thought I'd leave a comment. First time was when I found your piece on Deborah Simon, and old highschool friend. Second time in regard to Chaim Soutine, who I am writing about. Small world, I guess.

Keep up the great work-you have a wonderful blog! (My blog is a slacker blog these days)

Tree:

Thank you for the props. You may be slacking on the blog front, but have some nice posts in the "back catalog."

Good luck on the Soutine piece.

I saw this man's work at a Museum in Milwaukee. Jaw dropping. You have to have experienced a moment similar to those captured in still in his work to see why I'm moved to comment in such a way. If you are moved by the color of what you see quit your job and head to the north midwest and leave the highway for a while.

Post a Comment