"Power Figure: Nkondi" (detail)

Wood and metal

approx. 24 3/4 x 8 x 8 inches

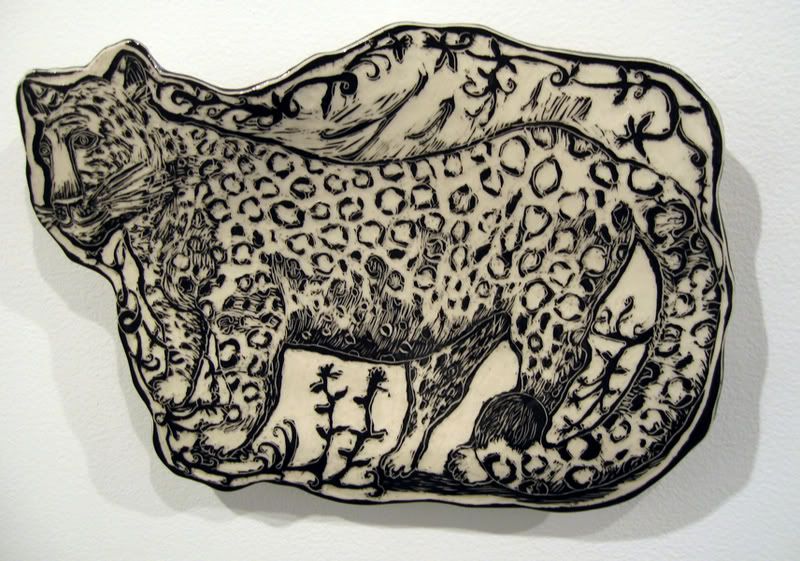

Kate Horne

"The Escape"

2006

Glazed porcelain & mason stain

9 x 12 x 1 inches

RARE: Artist collectives are a curious affair. The creative communion offered by a collective is appealing to many artists, yet so many of us would just as soon close the studio door and be left to our own devices. But that isolationist inclination makes the concept of a collective more valuable, particularly when the group concerns itself with a set of values or ideas, whether abstract or rigidly delineated, rather than some stylistic mode.

Amie Cunningham

"The Steadfast Warrior (Totem)"

2007

Maple wood, stain

78 x 17 1/2 x 20 inches

The Orchestra does just that. Pat Berran, Amie Cunningham, Candice Hoeflinger, and Kate Horne "[explore] the creation of modern-ray relics with a sensitivity to history, craft, and humans' precarious relationship with nature." An increasing number of young artists, myself among them, are setting up shop in this territory, an unsurprising migration given the complicated, fractured interdependency of modern man and the rest of it. The exemplary pieces in the RARE exhibition, "The Steadfast Warrior (Totem)," by Cunningham, and a series of porcelain relief paintings by Kate Horne, return to a totemic representation of Nature to "search for modern spiritual significance."

Kate Horne

"No Cookie"

2007

Glazed porcelain & mason stain

9 x 12 1/2 x 1 inches

Several months ago, I wrote about the paintings of Tom Uttech, a painter central to my pantheon. In that essay, I described totemic Nature as "a world of symbol and ecstatic interpretation" borne of sensual experience. That may seem a fanciful description to attach to Cunningham's totem or Horne's plates, but their work seems driven in part by a desire for natural reciprocity, a wanting to be alive as part of the greater weave. So many of us today yearn for this forgotten language, straining to apprehend the words despite our tongue's unfamiliarity. A rural childhood attunes the ear more than one spent in suburbia or the city; as we become an increasingly urban species, will we hear our history or taste our present without technological mediation?

"Bamana, Kore Hyena Mask, Mali, Africa"

Late 19th century

Wood, metal and leather

approx. 17 x 9 x 8 inches

Betty Cuningham: I can not say for sure whether or not the members of The Orchestra spent a lot of time outdoors as youngsters, but the artists responsible for the masks, clubs, statues, daggers, shields, and blankets included in "It's All Spiritual: Art from Tribal Cultures" definitely did. The show's curator, Alan Steele, writes, "The title...reflects the belief that all great art - to some degree or another - has a spiritual component and that nowhere is this seen better than in the tribal arts from remote cultures."

The spiritual component of these works - which, by the way, would be vetted even by the likes of John Dewey, as they are beautiful and utilitarian - removes the need for dressy conceptual underpinning. (Discouragingly, the reverse is also true; an alarming majority of contemporary art is largely short on "spirit." As contemporary humanity's relationship to Nature has become more clouded and distressed, so too has our awareness of the immediate, animating forces been thoroughly abstracted. We are no longer, then, satisfied with what is, and we develop a greater dependency on the theatre of possibility and promises of progress, in turn denying the present and the social body, and so exhibiting more pretense, anxiety, and depression. But this is a whole 'nother can of worms.)

"Power Figure: Nkondi"

Wood and metal

approx. 24 3/4 x 8 x 8 inches

One could argue, however, that the tribal works are conceptual in that they draw on the myths and magical narratives central to each culture, but those narratives are themselves the product of a local hunter-gatherer lifestyle, and the iconography is rooted in direct involvement with the resources and ecosystems from which the materials are drawn. I've long felt that the "primitive" works from the Africa, Oceania, and Americas collection at the Metropolitan Museum of Art are among the most inspiring under that roof. But seen in the context of so impressive and vast a hoard, those objects are most easily read as artifacts, as historical channel markers; the education offered by the museum presentation, while valuable, can distract from direct experience of the work, making it less edifying. This is one reason why we hear so much griping about the museum as mausoleum(1), and why the Betty Cuningham Gallery exhibition, smaller and more random in organization, allows viewers to experience the objects in much the same way they would contemporary works of art. Their vitality and relevance is immediately clear.

"It's All Spiritual" is a hopeful show. On the W train back to Queens I wondered if museums shouldn't start partnering with galleries on a more regular basis. Contemporary artists - indeed, all gallery goers - would be well served by it.

"Human/Prairie Dog Fetish, Southern Plains"

Last quarter of 19th century

Wood, green pigment, brass tacks

approx. 9 1/2 x 5 x 4 inches

Photo credit: all images, Hungry Hyaena

(1) Mausoleum or not, the Met is a true marvel. If you stop and think for a moment about what is housed inside...you gotta pinch yourself. Frankly, I don't spend nearly enough time there.

3 comments:

Thank you for introducing me to RARE. I went there this afternoon. I somehow did not enjoy the works as much as you describe. I do know how important totemic nature is for you but I think the prevalence of knockoff African art masks and the like on the streets of Manhattan has made me a bit inured to this stuff. Thank you once again though.

Sunil:

Interesting point, Sunil. I suppose context and intent have a lot to do with one's reading, but many of those knockoff masks are icons, even if they are made (manufactured) as kitsch mementos.

I have several "authentic" Oceanic masks in my collection (handed down from my grandfather's travels around the world) and when hung alongside an African knockoff, viewers always assume all the masks are the real deal. No matter their origin, the iconography is connected to the original source material; this is valuable in and of itself. There is still spirit in the finished product, then, even if the process becomes spiritless.

Having said that, I do feel more mana is invested in those pieces made with the magic in mind...and we don't find too many of those on SoHo streets.

All I have to say again, is Thank you. This blog is so refreshing. I am a little biased being that I am the artist who showed the porcelain relief paintings at Rare. It raised my spirits in winter seeing that you felt they were important and relevant enough to feature as examples from this past summer's show. All my work is heartfelt and I hope to invoke a spiritual experience on the end of the viewer. I love the way you write about the things you are taking in. I am an artist, object maker,and thus do not write and stick to things I do best-humbly making.

cheers

kate horne

Post a Comment