Mr. Misi on the studio floorI've seen a great deal of art these last two months, but I haven't been inclined to write a gallery report

since early April. The truth is, I probably wouldn't be writing one now but for the fact that my apartment and studio are hot and humid. Mr. Misi, my abundantly proportioned house cat, lolls about on the shady areas of the hardwood and at night I rest ice packs on the back of my neck to lower my core temperature. Even when outdoor conditions are tolerable, my apartment remains uncomfortable and, because sweat likes to sabotage watercolors, my painting time is limited to cooler days.

I

could install the window unit air conditioner, but I have trouble reconciling such profligate power consumption, especially in my poorly insulated apartment building. Instead, stubborn and sticky, I suffer through the summer months, longing for autumn, winter or spring (and residential architecture that better considers natural air flow).

Fortunately, computer keyboards aren't much bothered much by the occasional bead of sweat and, after noticing a small pile of press releases and notes saved from recent shows I enjoyed, I've decided to write about four of them.

+ + + + +

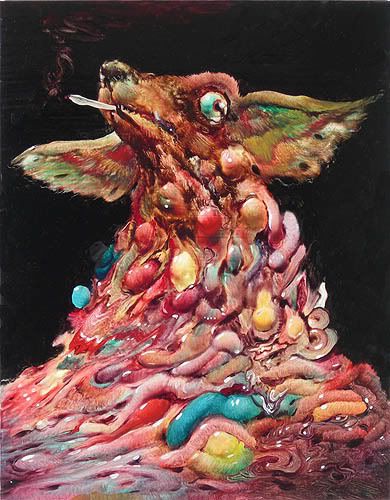

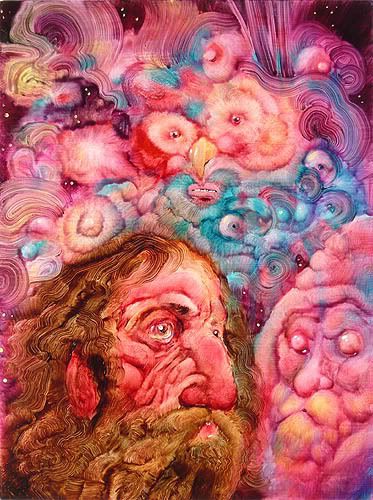

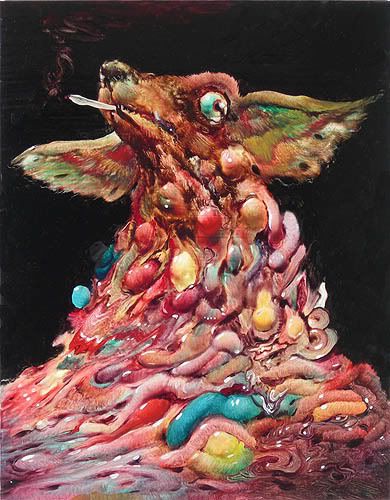

Andre Ethier

"Untitled"

2007

Oil on masonite

20 x 16 inchesDerek Eller Gallery:

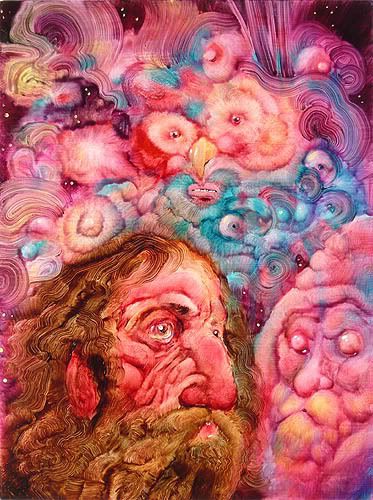

Andre Ethier's painting first came to my attention in late 2005, during his second solo show at Derek Eller Gallery. I was intrigued by the artist-musician's easy handling of oil paint, made fluid and in some areas translucent with the addition of various oil mediums. The works in that exhibition were luminous and colorful, but because Ethier mostly painted crude, ugly portraits, I was only able to admire the surface and color of his paintings. Ethier may have intended his slapdash treatment to read as nonchalance, but it instead seemed that the artist was unwilling to commit, perhaps frightened of accusations of earnestness.

Based on his follow-up at Eller, it appears that Ethier's reluctance to embrace his subjects has been overcome. Ethier also turns more to fantasy and myth in the recent work; his cast of characters now includes owl-headed figures, trolls, minotaurs, winged lions, and other, more fanciful creations. It is only when Ethier depicts one of these fantastic creatures with a cigarette or a peace sign medallion that I find myself again wondering if he isn't confusing defensive or cynical hipster posturing for intelligent mischief.

Andre Ethier

"Untitled"

2007

Oil on masonite

20 x 16 inchesBut I do not wish to focus on the show's few weaknesses, for Ethier includes some remarkable visual treats. The strongest paintings in the exhibition are also the most complex. Startling and captivating, Ethier's psychedelic pseudo-landscapes are every bit as beautiful as they are exhilarating. Three or four of the works in this show are strong enough, in fact, that a discerning viewer could return to them time and again, on each occasion discovering something new.

The gallery's press release suggests Ethier intends his portrayal of nature, both physical and metaphysical, to be "not just horrific, but...oppressively overwhelming and of epic proportion, filled with wonder and beauty as well." That sounds like a fair description of the philosophical

sublime. A great many artists attempt to celebrate that idea, often making works that are grand in scale. With his small paintings, however, Ethier fares better than most and in doing so reminds us that one needn't be dwarfed to be awed. I left the gallery thinking the artist, at his best, something of a latter-day, irreligious

Blake.

Andre Ethier

"Untitled"

2007

Oil on masonite

24 x 18 inches+ + + + +

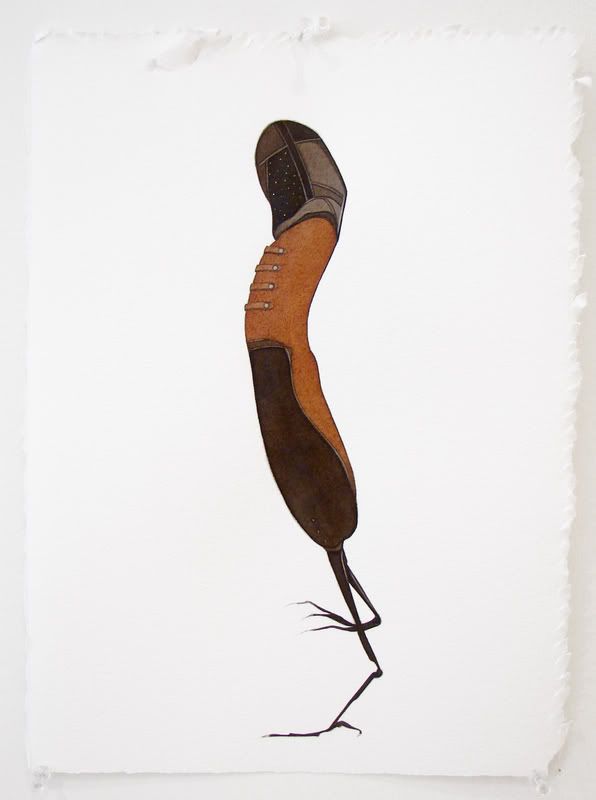

Amy Ross

"Cow Birch with Barred Owls"

2007

Graphite, watercolor and walnut ink on paper

30 x 22 inchesJen Bekman Gallery: I've written about

Amy Ross's paintings

on HH before. Several "delicate watercolors of hybrid bird-mushrooms" were included in "

Flight Plan," a group exhibition at

Morgan Lehman Gallery last year. I was at first skeptical of those works; they flirted with preciousness, but Ross's accomplished technique and "sincere integrity" won we over.

"

anima mundi," Ross's current solo show at Jen Bekman Gallery, includes a few of the smaller birdshroom works, but the majority of Ross's recent paintings picture birch tree groves. As with the birdshrooms, however, the trees are mutants, part birch, part animal. In some of the larger works, she-wolves, creatures with human bodies and wolf heads, gather among the mutant trees. Although the artist states that her work depicts the natural world "through the lens of genetic engineering and mutation gone awry," her hybrids seem less the product of mad science than an active, engaged imagination. Many of our species' primary stories - now considered quaint by all but a few remaining indigenous societies - are populated by hybrid creatures and shape shifters, and the owls, pheasants, she-wolves and hoofed trees of Ross's pictures seem borne of a desire on the part of the artist for natural communion, a longing to reconnect with our animal antecedence, rather than an interest in engineering mutants.

Amy Ross

"She-wolf Series #6"

2007

Graphite, watercolor and walnut ink on paper

30 x 22 inchesBut perhaps it doesn't matter whether Ross's morphs look inward, from whence we came, or forward, into that bright dream haze we call the future. Consider

Dr. Joe Rosen, the maverick plastic surgeon who argues that it is only a matter of time - he claimed five years,

um, five years ago - before humans have working wings. He believes our brains will build neural maps to control the new, surgically attached limbs. This claim would be more easily dismissed were Rosen not a respected physician at the

Dartmouth-Hitchcock Medical Center in New Hampshire and a professor at

Dartmouth College. (I highly recommend the terrific article, "

Dr. Daedalus," by Lauren Slater, in the October 2001 issue of

Harper's Magazine.) Who is to say that Dr. Rosen's surgical ambitions aren't also attached to some sort of longing for reconnection with the essential self, or animal?

Whatever Rosen's impetus may be, I don't see

X-Men in Ross's hybrids; her creatures are more akin to

Herne the Hunter, at least as Herne is portrayed in the

BBC Robin Hood series of the early 1980s. In that incarnation, Herne is a shaman who dons a stag head, appears in misty visions and speaks with booming authority to guide

Robin of Loxley, but, and this is the critical point, when Herne removes the stag head he is merely an old cripple who lives in a cave and fusses about with his kettle. He is still human despite - or perhaps more human, more vulnerable,

because of - his ability to commune with and fathom Nature's supernatural elements. Herne didn't graft antlers to his skull or replace his tired feet with hoofs; it is enough to be human and to pay attention. This is what it seems Ross is up to among the birch trees, and why I respond positively to her pictures.

Amy Ross

"Goat Birch with Goldfinches"

2007

Graphite, watercolor and walnut ink on paper

30 x 22 inches+ + + + +

Rachel Beach

"In The Round"

2007

Wood, wood veneer and oil paint

31 x 31 x 6 inchesHQ Gallery: I caught

Rachel Beach's exhibition, "Chicken & Egg," at HQ Gallery the day before it closed. I'd seen the work - handsomely crafted wood sculptures that seduce and deceive the eye - beforehand, but only in online reproductions. Although the images on

Beach's website are very good, her pieces need to be experienced in person. The intelligence and wit of this recent work is principally

sensed; intellectual consideration is secondary, at least initially.

Rachel Beach

"London Bridge"

2006

Wood, wood veneer and oil paint

15 x 65 x 5 1/2 inchesWhen I

did begin thinking about her hanging sculptures - and this only after I had left HQ -

M.C. Escher came to mind. Both artists share an interest in pattern and so-called "

optical illusion" but, more importantly, whether looking at a reproduced Escher drawing or one of Beach's wall works, conscious reflection is forced aside as my eyes and brain

struggle to make sense of the given information. There is no set way to see such works; viewers are provided with "ands" and "ors." The optical trickery at work here might be considered the biological equivalent of a

Zen koan, a question designed to root the practitioner in the moment. (Perhaps the title Beach chose for the show is an allusion to this sort of clear-headed uncertainty.)

Like many young artists today, Beach's designs and titles draw on a well of diverse sources - the arabesques of "Turkey's Nest" and the crenelations of "Wonderland," for example. Today we recognize most everything as familiar - the whole wide world is available on TV and

YouTube in bite-sized clips - and yet we don't really know any more about "the other" than our parents or grandparents did in their day. Entering "Chicken & Egg," I experienced something akin to a tourist's alienation, an unsettled feeling furthered by the optical push-pull play of the work: shiny wood veneer, used in many of the sculptures, contrasts with the natural grain of unpainted wood; colorful, bright oil paint abuts earthy ochres and wood flesh; a two dimensional reading slips easily, and quite suddenly, into three dimensions. The sculptures, hung close together in salon fashion, grant viewers a world of contour and symbol in proxy, but one that most of us are only capable of absorbing in the abstract. The sculptures remain an amalgam of half truths, misunderstandings, and alternative narratives - an epistemological riff on Escher's optical games - all of which are recognized in glimpses, before you're on to the next reading.

But - and this is no small thing - Beach's works look fantastic, not so much beautiful as they are sexy, alluring. Considered individually, these sculptures are a meeting of careful craft and chic styling. Taken as a whole, the exhibition is a

Necker portrait of our pastiche,

pomo worldview.

Rachel Beach

"Midnight"

2005

Wood, wood veneer and acrylic

23 x 35 x 6 1/2 - 2 inches (variable)+ + + + +

Boyce Cummings

"Black Trumpet"

2007

Oil on canvas

48 x 48 inchesJonathan Shorr Gallery:

Boyce Cummings is a close friend of mine. We met seven years ago in graduate school and it was immediately clear that we shared a deep affinity for wildlife and

ethology. We both recognize the more raw elements of our species' evolutionary indebtedness to the rest of it. Curiously, our work at the time drew on many of the same stylistic influences. Given these commonalities, we were bound to either despise one another or get along famously. Happily, it turned out to be the latter.

Boyce Cummings

"Owl Monkey"

2007

Graphite and ink on paper

8 x 11 inchesSo, sure, I'm a bit biased, but I think highly of Boyce's latest exhibition, "

Camouflage," at the Jonathan Shorr Gallery in SoHo. The show is predominantly comprised of small pencil and ink drawings, but also includes several sculptures and paintings. Boyce's facile line work - immediate, graphic and bold, but also graceful and emotive - is central to the success of most of the drawings, but it isn't only the artist's technical skill and confidence that animates the work. Cummings' art is nurtured by the artist's comfortable relationship with dark humor, violence and contradiction. Much of Cummings' imagery is freighted with meaning - bluebirds, trumpets, and nooses, for example - but even those works featuring more cryptic or unconscious signs/characters aggressively assert themselves, as though we should know exactly what variety of mischief is intended. Mischief, though, is probably too timid a word for much of this work; thoughtful viewers will connect the violence done to (or by) Cummings' animal hybrids with recurrent themes of social injustice. If this is a portrait of the human animal, it's a decidedly melancholy one.

Boyce Cummings

"Cat Mangler versus Rock Parrot" (detail)

2007

Epoxy resin and paint

Dimensions variableOne of my favorite works in "Camouflage" is a sculpture, "Cat Mangler versus Rock Parrot." In this piece, a thin, yellow feline stands atop a pile of earth and leaves, staring intently ahead at a fluttering blue bird. The blue bird, Yellow Cat presumes, could be dinner. But the bird is not, in fact, a bird at all, but a lure on the tail of a much larger, barrel-chested predator, also cat-like in nature, but possessing humanoid hands and a Confucian abundance of whiskers. With its frighteningly intent eyes focused on Yellow Cat, this larger beast, the Cat Mangler, twitches his tail lure to-and-fro, further entrancing his own potential meal. Just when I thought I had accounted for all the goings-on, I realized that the "pile of earth and leaves" on which Yellow Cat stands is a third hungry hunter. As I rounded the pedestal the face of an eagle-like mud beast came into view, Rock Parrot, with great, gnarled feet and distant, reptilian eyes. This third player in the drama, mimicking some unremarkable terrain, was ready to make a meal of the Mangler. It's a Rock Parrot-eat-Cat Mangler-eat-Yellow Cat world, I guess.

Many young artists - indeed, young adults generally -

talk about inequality and inequity, and of replacing the

flawed systems now in place with

something better. The French writer and philosopher

Voltaire believed the Christian church an unnecessary evil in his day and called for a total rejection of faith. His contemporaries responded by asking what the philosopher would put in place of the church. His exasperated response: "What! A ferocious beast has sucked the blood of my family; I tell you to get rid of that beast, and you ask me, what shall we put in its place!" Cummings' "Cat Mangler versus Rock Parrot" isn't just a window onto the wonders of natural selection and adaptation, or merely a reminder of the bloody violence inherent in any food chain; in the context of the exhibition (and today's fraught global theatre), it stands as a critique of our accepted social systems.

Boyce Cummings

"Cheers to the Field Workers"

2006

Collaged paper and acrylic paint on paper

10 x 15 inches+ + + + +Photo credits: Picture of Mr. Misi taken by Hungry Hyaena, 2007; Ethier images ripped from

Derek Eller Gallery website; Ross images ripped from

Jen Bekman Gallery website; Beach images courtesy the artist; Cummings images courtesy the artist