Michael Pollan working his garden

Curator Jodie Vicenta Jacobson cites Michael Pollan's The Botany of Desire as inspiration for "Implant," a Horticultural Society of New York exhibition sponsored and hosted by the international financial firm UBS. Jacobson is especially interested in Pollan's assertion that plants "use us" to further their evolutionary objectives. Although the notion that "plants control humans" is simplistic spin on what is in fact a complex web of interdependence, I smile on attempts to shake up (or down) the Judeo-Christian scalae naturae and so was predisposed to Jacobson's conceptualization of "Implant."

Unfortunately, most of the work Jacobson includes is only tangentially relevant to Pollan's thesis. Perhaps she believes that a curator should avoid intellectual illustration, that it is better for viewers to ruminate on the art with a loose curatorial contention in mind. Even if this is her stance, however, the selections seem arbitrary. In an accompanying brochure, she states that "the personal artist/subject bond is forged within a larger context of each individual's intrinsic understanding of his/her place in nature." The statement is valid (if vague) but, even though all the paintings, drawings, sculptures and videos in "Implant" include floral or botanical imagery, with few exceptions they are not about flowers or vegetation. Considered as a whole, "Implant" reflects, at worst, an intrinsic misunderstanding of our place in nature and, at best, a disinterested remove from the rest of life. One senses that many of these artists do think seriously about the so-called natural world, but have little firsthand experience with it.

Ann Craven

Studio view, December 2003

What, really, do such "art about art" works as Simon Starling's flowery chaise lounge and Karen Kilimnik's photographs of her still-life paintings have to do with the show's conceit? Or Carol Bove's bookshelf and Ann Craven's stacked watercolors? Certainly, Craven paints pretty canaries and orchids, but she is less concerned with the behavior or anthropological significance of Serinus and Orchidaceae than she is with questions of reproduction and commodification. The critical insistence that Craven's paintings "undercut Disney-esque references" and "raise questions about domestication...[of] once wild species"(1) is a stretch. The paintings don't communicate these ideas, and a viewer should not take a leap of faith that the paintings do not themselves impel (no matter what the accompanying wall text prompts).

One of the volumes included in Bove's bookshelf arrangement is propped open to a lovely botanical illustration; Bove's other books are placed spine-out, so that their titles can be easily read. The viewer is meant to ponder the connections between the artist's selections, but when I scan the books included, I don't find myself thinking on horticulture or the human/plant relationship; the work is principally concerned with 1960s soul searching.

What are these works doing here? Did Jacobson cherry-pick artists she likes and then try to find a connection between their work and the notion that plants control humans? That's a bass-akwards way to curate, but Jacobson herself lends credence to the charge in a brochure accompanying "Implant." A section called "Artist Focus: Felix Gonzalez-Torres" begins,

"I have been thinking about the 'Implant' exhibition in relation to Felix Gonzalez-Torres from its very inception. I consider him a keystone artist, not only for this exhibition, but for my entire curatorial program, and moreover in the world view of contemporary art. Contemplating Gonzalez-Torres' work in relationship to this specific exhibition has led me to various ends, both specific and open. The context of the exhibition is determined by the relationship between the artists involved, who, like Gonzalez-Torres, are not artists that primarily work with plants, but artists that have in a sense collaborated with plants to further a more specific idea. Therefore, 'Implant' is not narrowly themed, but quite open..."It seems as though Jacobson admits that her primary aim is to assemble a terrific group of artists in one exhibition, so why hem them in with an unsuitable theme? I suppose only Jacobson could answer the question (and I invite her to), but it's a shame that so many horticulture enthusiasts and botanists who visit the show will be at turns irritated and baffled by Ms. Jacobson's curation.

Granted, I'm more of a stickler for lucid curation than most. I assume that my grumbling about "Implant" will be shrugged off by many readers. Perhaps that's fair, but Jacobson's curatorial missteps might be more easily overlooked if they weren't a front-and-center distraction.

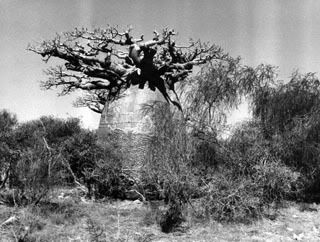

Tacita Dean

"Baobab III"

2001

Black & white photograph on fibre paper

26 1/2 x 41 inches

The exhibition overview ignored, many of the works in "Implant" are good to excellent: Darren Almond's long exposure photographs are meditative and beautiful; Zach Harris's otherworldly paintings descend from Charles Burchfield and Buddhist mandalas; Nick Cave's frantic flower tower mannequin is a playful delight; Tacita Dean's handsome photographs present the curious baobab tree, a species whose branches evoke neuronal dendrites. Yet none of these four artists contribute works that seem, as Jacobson put it, "rooted in a radical concept offered by horticultural author(2) Michael Pollan."

Curiously, it is often the more traditional work in "Implant" that best conveys her assertion that plants "choose" the artists to immortalize them. Carol Woodin's luminous watercolor on vellum paintings might even be dismissed as antique by contemporary art viewers. The works are more or less straightforward botanical undertakings, celebrating their subjects through careful observation, but they also reveal nature's amoral underbelly. Woodin's orchids all but drip with exotic sex, appealing to the voluptuary in each of us. Furthermore, Woodin's fine handling, unorthodox cropping and recessed presentation choices create an almost sacred experience for the viewer. In doing so, Woodin makes strange and wonderful that which we too often take for granted.(3)

Peter Coffin

"Untitled (Greenhouse)"

2002

Greenhouse, plants, speakers, instruments

96 x 96 x 120 inches

Peter Coffin's whimsical "Untitled (Greenhouse)" is a far cry from Woodin's work, but it is also succeeds with regard to Jacobson's theme. A small greenhouse is stocked with a variety of plants, but also with a drum kit, keyboard, guitars, microphones and amplifiers. Interested in musician-plant communication, Coffin booked several bands to play inside "Untitled (Greenhouse)" during the exhibition reception, and apparently intended that a soundtrack play whenever musicians were not performing. Distressingly, the greenhouse was quiet on the Friday morning of my visit. Not wanting the plants to go without aural stimulation, I entered the low-ceilinged structure to tap out a beat on the snare. (The plants, I'm sure, forgave my inadequacy.)

The feyness of Coffin's project makes it easy to like, but the artist is also riffing on the notion of pneuma, breath as vivifying force. As William Gass writes, "Language is born in the lungs and is shaped by the lips, palate, teeth, and tongue out of spent breath - that is, from carbon dioxide. That is why plants like being spoken to." Literally, our voice gives the plants breath. Taking this one step further, we can ask Proust's question of musical communication: "[Might music] not be the unique example of what might have been - if the invention of language had not intervened - the means of communication between souls?" If, as I mentioned earlier, Jacobson aims to make room for open-ended riffing on the part of the viewer, Coffin's greenhouse is her best pick.

By contrast, a photograph taken by Felix Gonzalez-Torres, the work (and artist) Jacobson had in mind since the inception of "Implant," is conceptually relevant, but aesthetically weak. The picture, "Untitled (Alice B. Toklas' & Gertrude Stein's Grave, Paris)," shows flowers planted and placed on the graves named in the title. The picture includes attractive flowers, but the photograph itself is unremarkable; it is not, as Jacobson contends, "a beautiful picture of flowers." Value is attributed by the viewer's knowing the specifics, namely that she is looking at flowers on the graves of two notables. Gonzalez-Torres is surely moved by the contemplation of displaced energy or reconstitution, by the realization that the flowers in a sense (and, in some respects, literally) feed on the break down of Toklas' and Stein's corpses. Although I share his appreciation for the contrast between individual mortality and communal integrity (or immortality), a poetic observation alone does not qualify as a work of visual art. Furthermore, the photograph highlights how very detached the industrialized imagination is from the natural world that shaped us. Though Gonzalez-Torres likely realized this, his picture reminds me that the mystical and holistic properties of plants, as part of an integrated worldview, are largely lost, the frame of reference fractured, secularized and compartamentalized. Plants placed atop a grave are mere signifiers of memorial; they no longer possess mana.

Yet I am hopeful. We are beginning to reconsider our relationship to the world around us. It is a good sign that, despite having very little practical experience with or knowledge of the outdoors, many of the artists included in "Implant" are inspired to incorporate floral imagery or ideas loosely connected to the plant world. Michael Pollan's is but one voice in a growing chorus encouraging urbanites and suburbanites to reconnect with the food chain by participating in community supported agriculture (CSA), reconsidering their usually negative opinion of hunting, and simply spending more time outdoors. Most importantly, however, plants are regaining a little of their mana among modern man.

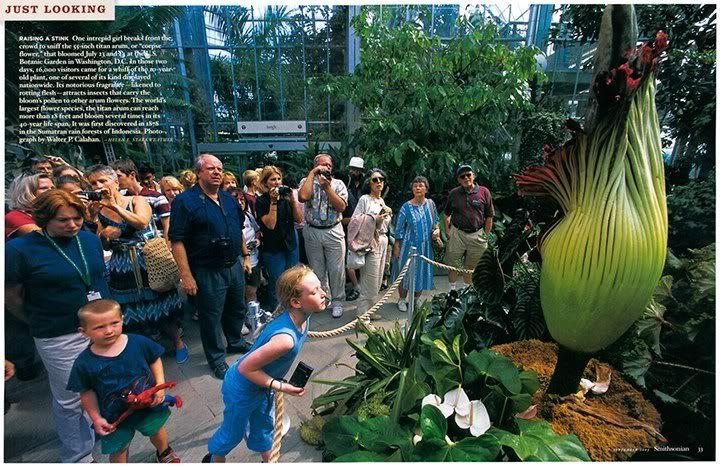

As I departed the UBS building, I thought of a photograph published in a magazine some years ago. When I returned to my apartment, I dug through my files and scrap books until I found it.

Man, meet plant!

Walter P. Calahan

2003

C-print for Smithsonian Magazine

(1) Jane Kallir, "The Animal in Contemporary Art"

(2) Horticultural author? Pollan is a now influential journalist and professor whose writing explores a range of issues related to moral and ethical stewardship and consumption, sustainability, anthropology, and psychology. Why pigeonhole him?

(3) Admiring her paintings, I recalled the experience of anticipatory wanting with Julia Randall's works at Jeff Bailey Gallery.

Photo credits: Michael Pollan working in his garden, ripped from The Sydney Morning Herald(via The New York Times); Ann Craven studio image, ripped from the artist's website; "Baobab III," ripped from Frith Street Gallery website; "Untitled (Greenhouse)," ripped from Phil Moore's Flickr collection; Corpse flower image ripped from Walter P. Calahan's website

3 comments:

hi Christopher. I enjoyed your thoughts in this post.

I particularly appreciated the following:"Considered as a whole, "Implant" reflects, at worst, an intrinsic misunderstanding of our place in nature and, at best, a disinterested remove from the rest of life. One senses that many of these artists do think seriously about the so-called natural world, but have little firsthand experience with it."

Firsthand experience is an interesting distinction. There is a lot of illustration influenced art work that seems to think nature (especially deer)is cute. First hand experience tracking deer and seeing evidence of their life (and death) cycle has taught me that nature is anything but cute. Nor is it cruel, it just is.

The recent slew of art shows about "nature" have me wondering how exactly most people define nature. In fact, the term "nature" has been bandied about so often and freely lately that I feel it is becoming empty of meaning.

To a number of humans I think "nature" just means-...like, trees and animals and stuff? I wonder if they include themselves/humankind in their definition. (dictionary.com offers multiple definitions for nature including both "the natural world as it exists without humans" and "elements of nature"(which I believe humans would be counted among).

If we are part of nature then is everything we have created an extension of our nature/nature? Where is the line between what is nature and what is not? I guess the interest in the subject is our simultaneous separation from and inclusion in nature. Although the separation is slightly self-imposed. When I am out camping/adventuring in the remaining wilds it doesn't take long for me to connect back into the bigger circle of life. I easily forget my daily separated human society existence even though I have spent more of my life in that world. Although my ultimate fantasy to be a lone huntergatheress may be leading me on to generalizations and assumptions here.

Ah, just things I think about. Hope you are well.

Hi, Molly.

Thanks for the comment.

These are thoughts that preoccupy me, as well. In fact, some of my upcoming posts will discuss these ideas a little more. Nature, as you say, is ambivalent. It can seem cruel; it can seem generous. "Seem" is the operative word. It is both cruel and generous, and so much more.

I grow weary of artists using Nature signifiers - white-tailed deer, barred owls, and the like - without convincing understanding. I realize that I am a more difficult viewer than most (at least with regard to this subject), but too many representations of the "natural world" are more Bambi than real.

I put "natural world" in quotes because, as you suggest, humans are very much a part of this world. A painting of an urban scene depicts the natural world and, indeed, the painting itself is natural. I believe strongly that everything humans have created is a part of Nature. Everything is integrated. The plastic in my computer keyboard is produced from oil, and that oil from dust and dirt, and that dust and dirt, in part, from the degeneration of ancestors' organs, both human and other. Viewing the world in this way, I do not draw any line between the natural and the artificial/human-made, except when writing, when it benefits easy communication.

By the way, Molly, I can't visit your blog anymore. Would you please sign me up as an invited guest? And why is visitation limited, if you're comfortable answering?

I hope that you are well, too!

awesome. I agree with you that humans and what we create are part of the natural world. But I had never considered my computer keyboards as being made up of my ancient ancestors before- that is definitely helping me make it through a long day at the office.

Similar but different to your weariness noted above,

I grow weary of using nature signifiers only to have them dismissed or go unnoticed. Often times it seems people believe such ideas pertain only to (non- human)animals and they lack the insight/interest to see such things in relationship to themselves or to see themselves as part of a larger chain of being.

I will invite you to read my blog but I have not posted on it for months.

Post a Comment