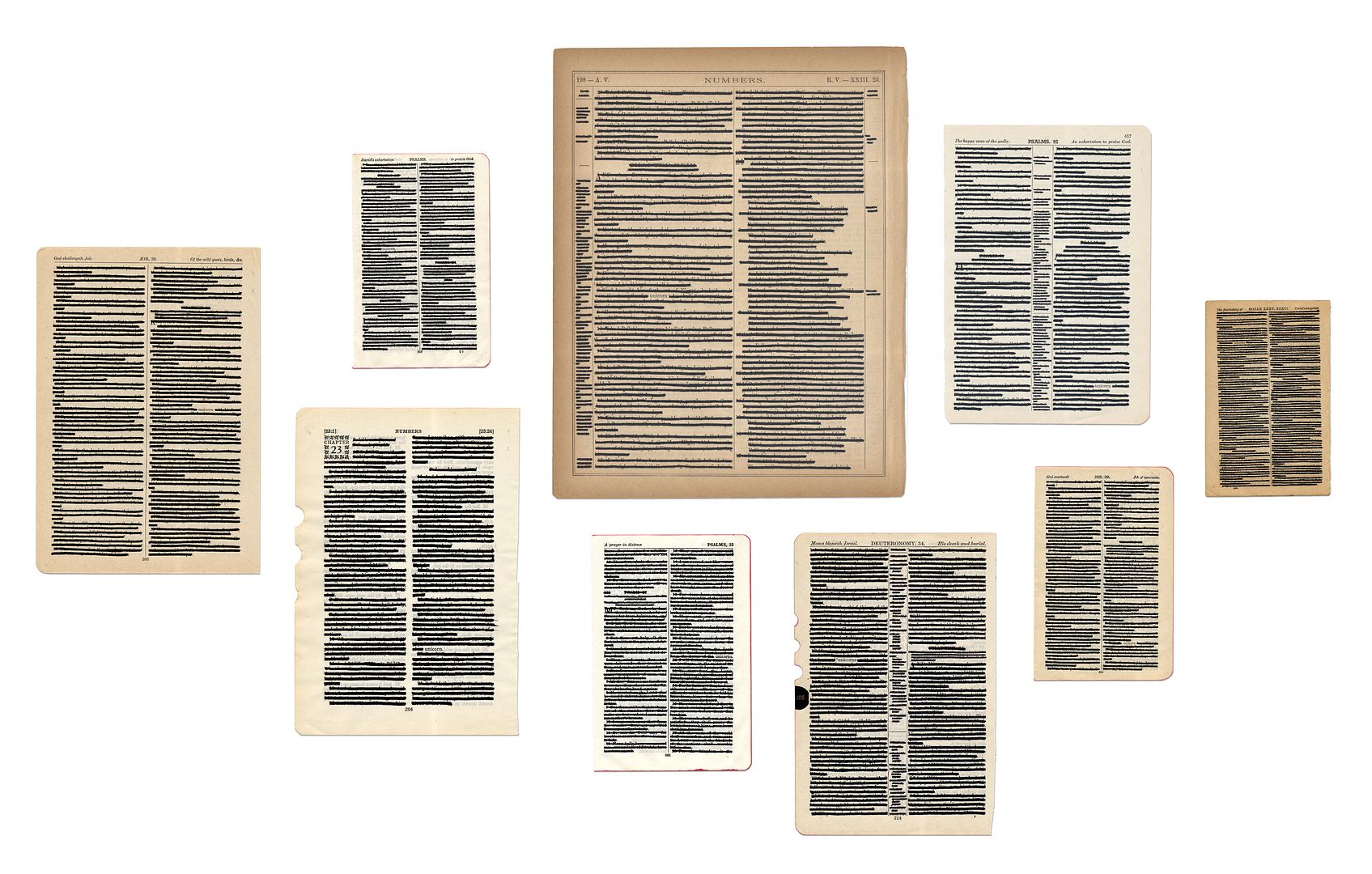

"9 Unicorns"

2011

Individual vintage bible pages

Large, juried shows are usually confused affairs. "Proof," the latest rendition of Southern Exposure's annual "entry-fee free juried exhibition of Northern California artists," is no exception. Of the 47 artworks (by as many artists), 5 pieces stand out: Kelly Falzone Inouye's "Tagging Sequence 1"; Robert Larkin's "Original Art"; Summer Mei Ling Lee's "Les preuves fatiguent la verite"; Kate Nartker's "West Main 1984"; and Someguy's "9 Unicorns."

"9 Unicorns," in particular, provided much to mull over. Someguy displays 9 pages from vintage Bibles; on each of these, all text except for the page heading and the word "unicorn" is blacked out. On his website, the artist states, "it's not commonly known, but the Bible mentions unicorns 9 times." I suspect that Someguy intends his handsomely presented editing job as a winking critique of religious literalism. By highlighting the occurrence of the word, the artist reminds viewers that mythological creatures populate the tome that literalists insist is non-fiction and most U.S. president-elects place their hands upon when they're sworn into office. Little girls notwithstanding, most of us are informed and sensible enough to dismiss unicorns as harmless hokum. Why, then, doesn't an overwhelming majority also view the Abrahamic narrative as an epic myth (i.e., fiction)?

Religious apologists point out that the Hebrew Bible makes no mention of unicorns. Instead, readers will find an ox, auroch, rhinoceros, or bison, depending on the edition. These more mundane creatures are indicated by the ancient Hebrew term re'em. The word was first translated as "unicorn" by the Greeks who, between 250 BCE and 100 CE, crafted the immensely important Septuagint, bringing the Hebrew scriptures to the Western world. Still, lest we too hastily ascribe an elevated rationality to the Jews of antiquity, scholars believe that re'em was not meant to describe an ordinary animal. The oral traditions of the Israelites and early Jews spoke of a powerful, monstrous auroch, a creature of gargantuan proportion, large enough to be mistaken for a mountain. Because they were unfamiliar with this monster bull, it's only sensible that the Greek translators and editors of the Septuagint substituted another fanciful creature, one better known to their audience; enter the unicorn.

Point being, the Bible, no matter the translation, is chock-a-block with fantasy. Most epic stories (and especially those with the staying power to warrant inclusion in a sacred narrative) are tall tales. Fictional or exaggerated narrative often pushes reality out of popular memory. The rhinoceros becomes a unicorn and the large crocodile becomes a dragon in the same way that the angler's fish grows through successive tellings; generations after the big mackerel was caught, it's Leviathan. But knowing how unicorns came to appear in some translations of the Bible doesn't justify easy dismissal of the sacred canon. Even for secular culture, the ancient stories are the closest approximation of universal myths, and they have much to offer readers with a critical bent -- much more, in fact, than they afford literalists.

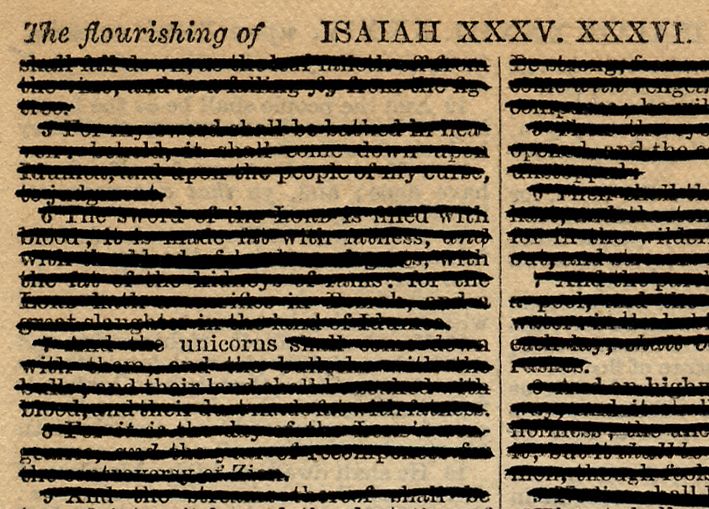

Detail of "9 Unicorns"

2011

Individual vintage bible pages

But "9 Unicorns" isn't just about the relationship between religious texts and fairy tales; it's also a critique of our postmodern malady. Today, technology and globalization expose us to a heretofore unprecedented quantity of information. As a result, it's progressively more difficult to wrest fact from fiction. As the late Senator Daniel Patrick Moynihan quipped, "Everyone is entitled to their own opinions, but not their own facts." Disappointingly, most of us reject Moynihan's gospel, instead opting to go at our texts with a Sharpie, making of them whatever we wish. This willful shirking of intellectual responsibility is amply on display in the fractious debate about the meaning of the United States Constitution and the legacy of our "founding fathers." Benjamin Franklin, one of those very prophets, smartly observed, "so convenient a thing it is to be a reasonable creature, since it enables one to find or make a reason for everything one has a mind to do."

Someguy's "9 Unicorns" evidences our species' taste for selective reading, subjective "truths," and rationalizations. Ever more interconnected, such an unhealthy disposition can become dangerous. Someguy's piece is a visual fable of sorts, cautioning us to master our appetites.

Detail of "9 Unicorns"

2011

Individual vintage bible pages

Image credits: all someguy images, courtesy the artist

1 comment:

Related to the above piece, I suggested reading Edward Rothstein's New York Times review of "Manifold Greatness: The Creation and Afterlife of the King James Bible." The below excerpt is particularly curious (and amusing).

"Because Shakespeare was still alive when the translation was published, many came to believe (without any basis in fact) that he was one of its creators. The show even displays publications arguing for his authorship using arcane analyses of secret allusions to his name in the King James text. (In Psalm 46, for example, the word “shake” is 46 words from the beginning and “speare” 46 from the end; Shakespeare was 46 in 1610 as the translation was being completed.)"

Arcane assertions abound when it comes to the Bible! You gotta love it.

Post a Comment