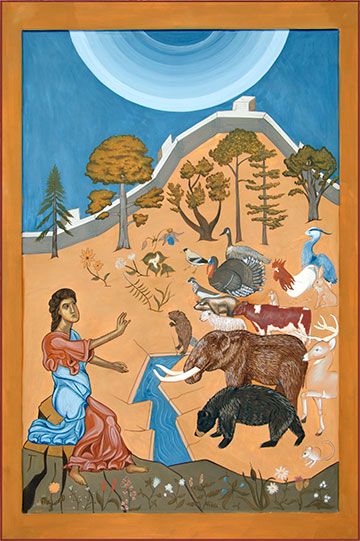

Christopher van Donkelaar

"Adam Naming the Animals"

Handmade pigments and mixed media

2008

"Praise to the first man who wrote down this joy clearly, for we cannot remain in love with what we cannot name."A lover of etymology and taxonomy, one of my most cherished reference books is Arthur Frederick Gotch's Latin Names Explained: A Guide to the Scientific Classification of Reptiles, Birds and Mammals. In it, Gotch catalogs and dissects the scientific names of some 4,000 animal species. That number appears relatively insignificant when we consider that biologists estimate 25,000 species of bird, mammal, and reptile currently exist on Earth, but Gotch's record is so far unparalleled. Each entry provides the animal's common and scientific names, followed by an explication of the Latin and Greek and, sometimes, a blurb about the species' range and habitat.

- Robert Bly

For example, consider Gotch's entry on one of my very favorite North American snake species:

Copperhead Agkistrodon contortrixAlthough the range information suggests that the copperhead is more confined to the southeastern United States than the species and subspecies actually are - they thrive in New York State, for example - Gotch's entry informs readers that the snake commonly called a copperhead is universally and technically named Fish-hook shaped tooth twister or, if you prefer, The Twisting One With Hook Shaped Teeth. Knowledge of this name allows me to appreciate the beautiful reptile from another angle.

agkistrodon (Gr) a fish-hook; odon (Gr) a tooth; a reference to the curved fangs, though of course they are not barbed; contorqueo (L) I twist, turn; contortus (L) full of turns, twisted; contortrix (L) one that is able to turn, twist. Inhabiting the south-eastern part of the USA including Florida. The top of the head is reddish brown.

But what's in a name, really?

Although I'm generally baffled by Biblical literalism, I appreciate the Genesis accounts of creation for their gratifying metaphor. In particular, I'm drawn to rabbinic and Jewish mystics' interpretations of the conjoined, aboriginal narratives. More so than their Christian counterparts, Jewish theologians and mystics endow language and names with ontological significance. The Hebrew alphabet is understood as a powerful code: the written word is creative potential, and the spoken word, procreative. The god of Genesis 1 creates neither with a wave of the hand nor by shaping raw material, but by speaking the world into being; annunciation and incantation are the means of creation. Because of the vocative nature of naming, observant Jews place great value on words and speech. (They are even prohibited utterance of the tetragrammaton, the four-letter Hebrew name of God, transliterated as Yahweh. Appropriately enough, the colloquial name for God is Hashem, or "the word.")

In Genesis 2, the creator god is anthropomorphized and physically involved with creation, shaping man and the other animals from earth. Yet the power of language and names remains significant in this account. God asks Adam, the first naked ape, to name all of the other animal species. That's no mean task, and apparently Adam died before he finished the job. His descendants, at least the taxonomists among them, are still working at the task of naming.

But even those individuals who do not share my affection for taxonomy will find value in a practice of observation and naming. As Carol Kaesuk Yoon writes in her recent New York Times paean to taxonomy, "Reviving the Lost Art of Naming the World,"

"Even when scads of insistent wildlife appear with a flourish right in front of us, and there is such life always — hawks migrating over the parking lot, great colorful moths banging up against the window at night — we barely seem to notice. We are so disconnected from the living world that we can live in the midst of a mass extinction, of the rapid invasion everywhere of new and noxious species, entirely unaware that anything is happening. Happily, changing all this turns out to be easy. Just find an organism, any organism, small, large, gaudy, subtle — anywhere, and they are everywhere — and get a sense of it, its shape, color, size, feel, smell, sound. Give a nod to Professor Franclemont and meditate, luxuriate in its beetle-ness, its daffodility. Then find a name for it. Learn science’s name, one of countless folk names, or make up your own. To do so is to change everything, including yourself. Because once you start noticing organisms, once you have a name for particular beasts, birds and flowers, you can’t help seeing life and the order in it, just where it has always been, all around you."Beautiful. Let's name something.

See also "The Plant Whisperer," another brief HH essay considering similar ideas.

Image credit: van Donkelaar painting ripped from the Nurturing Faith website

2 comments:

the naming of names is the first poem.

Ben:

Thanks for reading, and for leaving the lovely thought. I read the poem of yours from which it is drawn, and quite like it.

Post a Comment