This is the last week of my three person show, "Animus Botanica," at Denise Bibro Gallery. If you haven't yet seen the exhibition and can make it to Chelsea this Saturday (or before), please do!

Also, today is the final day of the group show, "Year of the Rat," on display at Archibald Arts. If you're not slaving at the wage gig this afternoon, take time for some art viewing...and to ruminate on the capitalist condition.

Tuesday, September 30, 2008

Monday, September 29, 2008

"Implant" at UBS Art Gallery

Michael Pollan working his garden

Curator Jodie Vicenta Jacobson cites Michael Pollan's The Botany of Desire as inspiration for "Implant," a Horticultural Society of New York exhibition sponsored and hosted by the international financial firm UBS. Jacobson is especially interested in Pollan's assertion that plants "use us" to further their evolutionary objectives. Although the notion that "plants control humans" is simplistic spin on what is in fact a complex web of interdependence, I smile on attempts to shake up (or down) the Judeo-Christian scalae naturae and so was predisposed to Jacobson's conceptualization of "Implant."

Unfortunately, most of the work Jacobson includes is only tangentially relevant to Pollan's thesis. Perhaps she believes that a curator should avoid intellectual illustration, that it is better for viewers to ruminate on the art with a loose curatorial contention in mind. Even if this is her stance, however, the selections seem arbitrary. In an accompanying brochure, she states that "the personal artist/subject bond is forged within a larger context of each individual's intrinsic understanding of his/her place in nature." The statement is valid (if vague) but, even though all the paintings, drawings, sculptures and videos in "Implant" include floral or botanical imagery, with few exceptions they are not about flowers or vegetation. Considered as a whole, "Implant" reflects, at worst, an intrinsic misunderstanding of our place in nature and, at best, a disinterested remove from the rest of life. One senses that many of these artists do think seriously about the so-called natural world, but have little firsthand experience with it.

Ann Craven

Studio view, December 2003

What, really, do such "art about art" works as Simon Starling's flowery chaise lounge and Karen Kilimnik's photographs of her still-life paintings have to do with the show's conceit? Or Carol Bove's bookshelf and Ann Craven's stacked watercolors? Certainly, Craven paints pretty canaries and orchids, but she is less concerned with the behavior or anthropological significance of Serinus and Orchidaceae than she is with questions of reproduction and commodification. The critical insistence that Craven's paintings "undercut Disney-esque references" and "raise questions about domestication...[of] once wild species"(1) is a stretch. The paintings don't communicate these ideas, and a viewer should not take a leap of faith that the paintings do not themselves impel (no matter what the accompanying wall text prompts).

One of the volumes included in Bove's bookshelf arrangement is propped open to a lovely botanical illustration; Bove's other books are placed spine-out, so that their titles can be easily read. The viewer is meant to ponder the connections between the artist's selections, but when I scan the books included, I don't find myself thinking on horticulture or the human/plant relationship; the work is principally concerned with 1960s soul searching.

What are these works doing here? Did Jacobson cherry-pick artists she likes and then try to find a connection between their work and the notion that plants control humans? That's a bass-akwards way to curate, but Jacobson herself lends credence to the charge in a brochure accompanying "Implant." A section called "Artist Focus: Felix Gonzalez-Torres" begins,

"I have been thinking about the 'Implant' exhibition in relation to Felix Gonzalez-Torres from its very inception. I consider him a keystone artist, not only for this exhibition, but for my entire curatorial program, and moreover in the world view of contemporary art. Contemplating Gonzalez-Torres' work in relationship to this specific exhibition has led me to various ends, both specific and open. The context of the exhibition is determined by the relationship between the artists involved, who, like Gonzalez-Torres, are not artists that primarily work with plants, but artists that have in a sense collaborated with plants to further a more specific idea. Therefore, 'Implant' is not narrowly themed, but quite open..."It seems as though Jacobson admits that her primary aim is to assemble a terrific group of artists in one exhibition, so why hem them in with an unsuitable theme? I suppose only Jacobson could answer the question (and I invite her to), but it's a shame that so many horticulture enthusiasts and botanists who visit the show will be at turns irritated and baffled by Ms. Jacobson's curation.

Granted, I'm more of a stickler for lucid curation than most. I assume that my grumbling about "Implant" will be shrugged off by many readers. Perhaps that's fair, but Jacobson's curatorial missteps might be more easily overlooked if they weren't a front-and-center distraction.

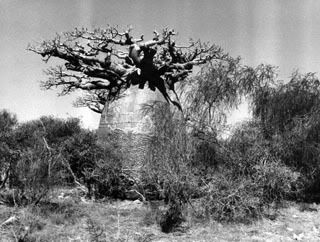

Tacita Dean

"Baobab III"

2001

Black & white photograph on fibre paper

26 1/2 x 41 inches

The exhibition overview ignored, many of the works in "Implant" are good to excellent: Darren Almond's long exposure photographs are meditative and beautiful; Zach Harris's otherworldly paintings descend from Charles Burchfield and Buddhist mandalas; Nick Cave's frantic flower tower mannequin is a playful delight; Tacita Dean's handsome photographs present the curious baobab tree, a species whose branches evoke neuronal dendrites. Yet none of these four artists contribute works that seem, as Jacobson put it, "rooted in a radical concept offered by horticultural author(2) Michael Pollan."

Curiously, it is often the more traditional work in "Implant" that best conveys her assertion that plants "choose" the artists to immortalize them. Carol Woodin's luminous watercolor on vellum paintings might even be dismissed as antique by contemporary art viewers. The works are more or less straightforward botanical undertakings, celebrating their subjects through careful observation, but they also reveal nature's amoral underbelly. Woodin's orchids all but drip with exotic sex, appealing to the voluptuary in each of us. Furthermore, Woodin's fine handling, unorthodox cropping and recessed presentation choices create an almost sacred experience for the viewer. In doing so, Woodin makes strange and wonderful that which we too often take for granted.(3)

Peter Coffin

"Untitled (Greenhouse)"

2002

Greenhouse, plants, speakers, instruments

96 x 96 x 120 inches

Peter Coffin's whimsical "Untitled (Greenhouse)" is a far cry from Woodin's work, but it is also succeeds with regard to Jacobson's theme. A small greenhouse is stocked with a variety of plants, but also with a drum kit, keyboard, guitars, microphones and amplifiers. Interested in musician-plant communication, Coffin booked several bands to play inside "Untitled (Greenhouse)" during the exhibition reception, and apparently intended that a soundtrack play whenever musicians were not performing. Distressingly, the greenhouse was quiet on the Friday morning of my visit. Not wanting the plants to go without aural stimulation, I entered the low-ceilinged structure to tap out a beat on the snare. (The plants, I'm sure, forgave my inadequacy.)

The feyness of Coffin's project makes it easy to like, but the artist is also riffing on the notion of pneuma, breath as vivifying force. As William Gass writes, "Language is born in the lungs and is shaped by the lips, palate, teeth, and tongue out of spent breath - that is, from carbon dioxide. That is why plants like being spoken to." Literally, our voice gives the plants breath. Taking this one step further, we can ask Proust's question of musical communication: "[Might music] not be the unique example of what might have been - if the invention of language had not intervened - the means of communication between souls?" If, as I mentioned earlier, Jacobson aims to make room for open-ended riffing on the part of the viewer, Coffin's greenhouse is her best pick.

By contrast, a photograph taken by Felix Gonzalez-Torres, the work (and artist) Jacobson had in mind since the inception of "Implant," is conceptually relevant, but aesthetically weak. The picture, "Untitled (Alice B. Toklas' & Gertrude Stein's Grave, Paris)," shows flowers planted and placed on the graves named in the title. The picture includes attractive flowers, but the photograph itself is unremarkable; it is not, as Jacobson contends, "a beautiful picture of flowers." Value is attributed by the viewer's knowing the specifics, namely that she is looking at flowers on the graves of two notables. Gonzalez-Torres is surely moved by the contemplation of displaced energy or reconstitution, by the realization that the flowers in a sense (and, in some respects, literally) feed on the break down of Toklas' and Stein's corpses. Although I share his appreciation for the contrast between individual mortality and communal integrity (or immortality), a poetic observation alone does not qualify as a work of visual art. Furthermore, the photograph highlights how very detached the industrialized imagination is from the natural world that shaped us. Though Gonzalez-Torres likely realized this, his picture reminds me that the mystical and holistic properties of plants, as part of an integrated worldview, are largely lost, the frame of reference fractured, secularized and compartamentalized. Plants placed atop a grave are mere signifiers of memorial; they no longer possess mana.

Yet I am hopeful. We are beginning to reconsider our relationship to the world around us. It is a good sign that, despite having very little practical experience with or knowledge of the outdoors, many of the artists included in "Implant" are inspired to incorporate floral imagery or ideas loosely connected to the plant world. Michael Pollan's is but one voice in a growing chorus encouraging urbanites and suburbanites to reconnect with the food chain by participating in community supported agriculture (CSA), reconsidering their usually negative opinion of hunting, and simply spending more time outdoors. Most importantly, however, plants are regaining a little of their mana among modern man.

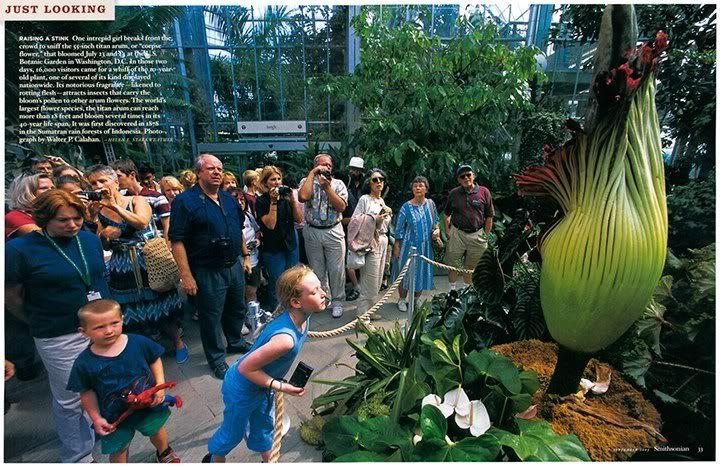

As I departed the UBS building, I thought of a photograph published in a magazine some years ago. When I returned to my apartment, I dug through my files and scrap books until I found it.

Man, meet plant!

Walter P. Calahan

2003

C-print for Smithsonian Magazine

(1) Jane Kallir, "The Animal in Contemporary Art"

(2) Horticultural author? Pollan is a now influential journalist and professor whose writing explores a range of issues related to moral and ethical stewardship and consumption, sustainability, anthropology, and psychology. Why pigeonhole him?

(3) Admiring her paintings, I recalled the experience of anticipatory wanting with Julia Randall's works at Jeff Bailey Gallery.

Photo credits: Michael Pollan working in his garden, ripped from The Sydney Morning Herald(via The New York Times); Ann Craven studio image, ripped from the artist's website; "Baobab III," ripped from Frith Street Gallery website; "Untitled (Greenhouse)," ripped from Phil Moore's Flickr collection; Corpse flower image ripped from Walter P. Calahan's website

Thursday, September 25, 2008

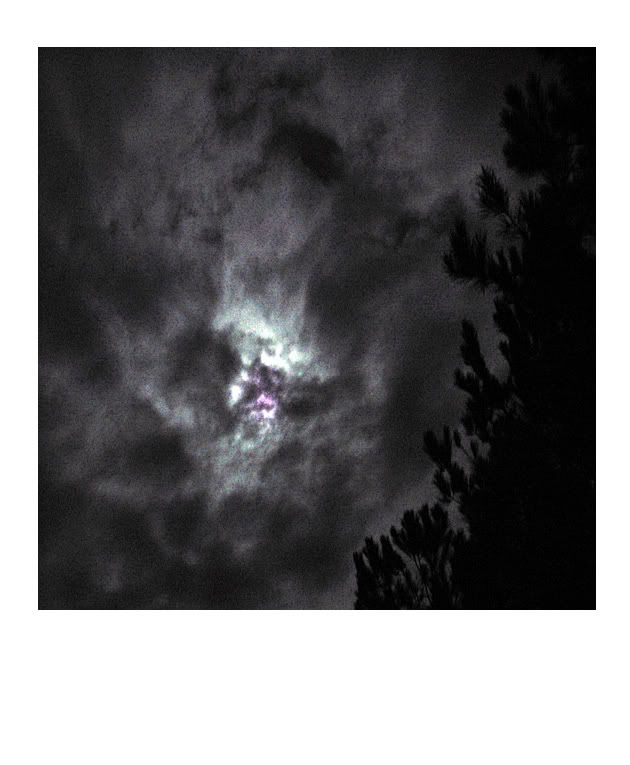

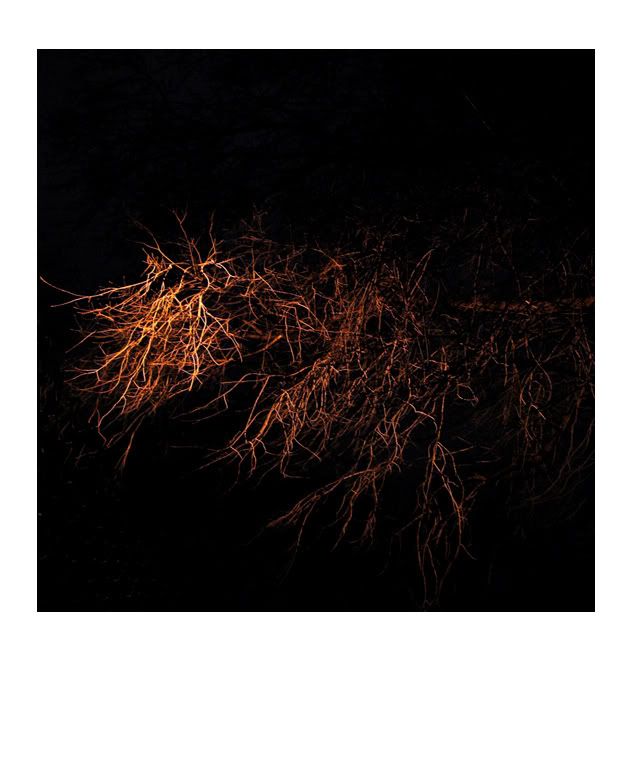

Almost Twilight

The gateway to all understanding."

-Lao tzu, "Tao Te Ching"

In New York, recent mornings have greeted us with a pleasant chilliness. Fall is almost here, and winter is just around the corner. For most folks, the prospect is daunting. Not so for me. Each year at this time, a bounce finds my step and I'm happily overwhelmed by a spate of ideas. I know, however, that the creative juices will before long transmute into keen brooding. Late fall and winter nurture a pensive mind.

When the afternoons darken and the mercury dips, I like to take bundled winter strolls through the streets of Manhattan or Queens. Other pedestrians hustle about, intent on achieving their respective indoor destinations, but I find my thoughts best served by a steady pace, one forgiving of some intentioned aimlessness. I spend these walks looking up to where the melancholic sky meets the buildings that scrape it, admiring the resilience of foraging House sparrows, taking note of the way traffic lights glow more brightly in crisp, cold air and marveling over the many lives that move around me. I like to think of this mindful meandering as a form of prayer, or perhaps a communion, and I treasure the insights that are sometimes happened upon.

Curious about the rites, beliefs and texts of various religions (and particularly those of Judaism), I've been thinking this week about the coming high holy days. Next Monday is Rosh Hashanah, the first of Judaism's ten "days of awe," or Yamim Noraim. Like my winter walks, the Yamim Noraim are given over to contemplation. During the ten high holy days, an observant Jew should meditate on the actions of his last twelve months and, then, on Yom Kippur, the last of the "days of awe," fast and repent for any wrongdoing. In other words, a conscientious Jew begins the new year by reckoning with his past. Although Rosh Hashanah is only one of four Jewish New Years, each attached to a specific set of guidelines and meaning, I find the holiday's position with regard to the seasons of particular interest.

Considered the New Year for humans, animals, calendar calculation and contracts, Rosh Hashanah arrives with the ploughing of summer into fall. If one considers fall equivalent to dusk and winter to night, then the Jewish New Year, in the northern hemisphere, like the Jewish day, begins at twilight. This interpretation does not hold with regard to the geography and climate of the Torah's narrative; Palestine is (and was) a land with only two notable seasons, called in the Talmud "the days of sun" and "the days of rain," but our understanding of scripture, be it theological or scientific, must change with context if it is to remain relevant to our contemporary lives. The notion of a day extending from sunset to sunset runs slightly counter to the popular conception of morning time as a birthing, or spring, with the hours moving then through summer at mid-day, fall in the evening and finally into winter, night and death. But the Judeo-Christian tradition is pastoral, founded on an agricultural reckoning of the lunar and solar cycles. It makes sense, then, that the day should end as light fades or vanishes, and begin again while it remains dark. In rural farming communities, this pattern holds today, though the blue glow of television has altered habits in even the most rural of counties. Still, as Oscar Wilde, a consummate urbanite, quipped, "people in the country get up early because there's so much to do. They go to bed early, because there's nothing to talk about."

Growing up in such a community, I learned early that if twilight is a conclusion for the farmer, it is a commencement for many other creatures. A patient hunter who remains in his deerstand as the final light retreats might see bats dart and dip in aerial pursuit of insects. He may also see an opossum, fox, raccoon, skunk or even his intended quarry, deer, though it is not legal to shoot after the sun sets. Driving or biking on "backroads," these animals reveal themselves by reflecting light from a car's headlights or a bike's front beam. The tapetum lucidum, a layer of tissue behind the retina of crepuscular and nocturnal species, allows the animal to see better in near or total darkness, but this layer also produces eyeshine that discloses the creature's presence to human torch bearers. Depending on the species and the angle of approach, we can identify the animal by the color of its eyeshine: the white-yellow lights at knee height belong to the red fox; the orange orbs in the low branches of a tree are an opossum; the yellow beams tall over the road are white-tailed deer; the brilliant white spots that appear so near the ground expose a resting whippoorwill.

Imagine the shock of the early humans when they first noticed the glowing embers that moved just outside the reach of their warm firelight. The agricultural tribes that would become the people of the Torah, having abandoned much of their nomadic, hunter-gatherer roots, were particularly afraid of the dark, creeping world outside that circle of light. To be caught in the gloaming, away from a human settlement or encampment, was surely a terrifying possibility.

Indeed, the dark months, like those black, antediluvian nights, remain an ordeal for many people . But they can also be understood as a gateway opportunity. It is fitting, I think, that Jews begin their new year by taking stock, a formidable task if undertaken with thoroughness and honesty. I approached my experiences with hallucinogenic drugs in an analogous way; what most people would call a "bad trip," I viewed as an opportunity for introspection. 'Why has my brain created this awful idea?,' I asked myself. 'What does that tell me about my relationship to x or y, or about my fear of a, b or c?' The cold, gloomy months, like bad trips, nightfall and deep melancholy, can be challenging, even endangering, but in an increasingly mediated and accelerated world culture, the difficult passages are of premium value.

I'm neither Jewish nor properly Christian, despite an Episcopal baptism. I wouldn't describe myself as lapsed, either; from early adolescence, I proudly labelled myself an atheist. Today, however, I prefer the term pantheist, and I find my interest in faith choices and spirituality reinvigorated, though my conception of God is fundamentally unchanged from my Nietzsche-Nine Inch Nails days.

I've taken particular interest in Jewish practice, both historical and contemporary, although the concept of an omniscient, interventionist creator is anathema. Unitarian Universalism, a relatively young sect that grew out of Unitarianism, is also exciting to me, though it is so all-inclusive and plural - Christian, Muslim and Jewish believers sit in UU pews alongside Buddhists, atheists and agnostics - that it might be more fairly deemed an ethical community than a religious sect. But whatever label I eventually pin to my lapel (or discard), periods of solemn self-examination are likely to remain a critical part of my identity and annual experience, and these have so far coincided with winter and come on the heels of a fall surge in the creative impulse.

Although modernity misunderstands fall to be the beginning of an end, it is only another beginning. Shana tova umetukah, folks. My favorite season is moving in, and our shadows grow longer.

Photo credits: "Athens Park, Astoria," "Central Park, Manhattan," "Heron's Foot Moon, Virginia," "Branches," all by Christopher Reiger, 2007 and 2008

Sunday, September 21, 2008

Like Brushstrokes

Christopher Reiger

"from the tangled vegetation"

2006-2007

Watercolor, gouache, sumi ink and marker on Arches paper

22 x 22 inches

"The great birds paced their own glassy reflections before pulling up like brushstrokes to stand in the shallows of the far shore."

- Matthew Power, "Mississipi Drift: River vagrants in the age of Wal-Mart"

Friday, September 19, 2008

Everybody's talking about it...

...but few folks have anything this worthy to contribute.

Bosko Blagojevic's "Hard to See, Harder to Imagine" post at ArtCal Zine is only a modest taking-stock, but it reads like a prose poem. It isn't just our ailing economy that needs examination; indeed, the capitalistic economic machine always operates in a fugue.

Note: This post follows an auction announcement, albeit a benefit auction. As Alanis would say, isn't it ironic?

Bosko Blagojevic's "Hard to See, Harder to Imagine" post at ArtCal Zine is only a modest taking-stock, but it reads like a prose poem. It isn't just our ailing economy that needs examination; indeed, the capitalistic economic machine always operates in a fugue.

"Financial journalism, and economics since around the mid 17th century, has increasingly been about abstractions: intricate movements of people, money and material described and occasionally visualized, but remaining essentially invisible. They endure, like climate change and remote international conflicts, as that which might inspire excitement, worry, fear, or action - and yet necessarily demand a kind of belief in order to do so. Belief in the economy, as belief in anything else, becomes a certain emotional temperature that elevates a thing from an idea to a fact. It cannot be anything but this. So it may be with a sense of puzzled anxiety, an anxiety without an image or a face, that one reads in today's Times of the $85 billion Federal loan to save A.I.G., the capsizing international insurance giant. Equal puzzlement or slightly chastened awe, perhaps, might be inspired on the same day upon reading, on top of Artforum.com's news page, of Damien Hirst's potentially precedent-setting 2-day primary market auction sale, collecting for the artist $200.8 million in the sale of all but three of the 167 works to see the auction block. These numbers in their excess, of profits or deficits, seem to become less real with each shift in the order of magnitude, or move of the decimal point."

Note: This post follows an auction announcement, albeit a benefit auction. As Alanis would say, isn't it ironic?

Sunday, September 14, 2008

Dieu Donne Auction reception this week

I donated an original work, "A Posthumous Shame #2," to the upcoming Dieu Donne Papermill Benefit Auction and Exhibition. Many terrific artists are participating.

+++++

Benefit exhibition and auction honoring David Kiehl

(Conducted by Hugh Hildesley of Sotheby's)

September 18th – October 11th

Exhibition reception: Thursday, September 18, 6–8 PM

Auction: Tuesday, October 14

Silent Auction preview here.

Live auction preview here.

Christopher Reiger

"A Posthumous Shame #2"

2008

Sumi ink, watercolor and thread on handmade paper

6 1/2 x 9 inches

+++++

Benefit exhibition and auction honoring David Kiehl

(Conducted by Hugh Hildesley of Sotheby's)

September 18th – October 11th

Exhibition reception: Thursday, September 18, 6–8 PM

Auction: Tuesday, October 14

Silent Auction preview here.

Live auction preview here.

Christopher Reiger

"A Posthumous Shame #2"

2008

Sumi ink, watercolor and thread on handmade paper

6 1/2 x 9 inches

Monday, September 08, 2008

The Benefits of Flight-induced Relativism

Edward Burtynsky

"Silver Lake Operations #2, Lake Lefroy, Western Australia"

2007

Digital chromogenic print

Dimensions variable

"From the height of ten thousand feet, the earth appears to the human eye as it appears to the eye of the camera; that is to say, all history is reduced to the accidents of nature. This has the salutary effect of making historical evils, like national divisions and political hatreds, seem absurd.

...

If the effects of distance between the observer and the observed were mutual, so that as the objects on the ground shrank in size and lost their uniqueness, the observer in the airplane felt himself shrinking and becoming more and more generalized, we should either give up flying or create heaven on earth."

-W.H. Auden

For more thoughts on altitude granted relativism, read my post, "The Absurd Whole," a response to an exhibition of Michael Light's photographs.

Photo credit: Burtynsky photograph ripped from artnet

Wednesday, September 03, 2008

This week; two NYC exhibition receptions

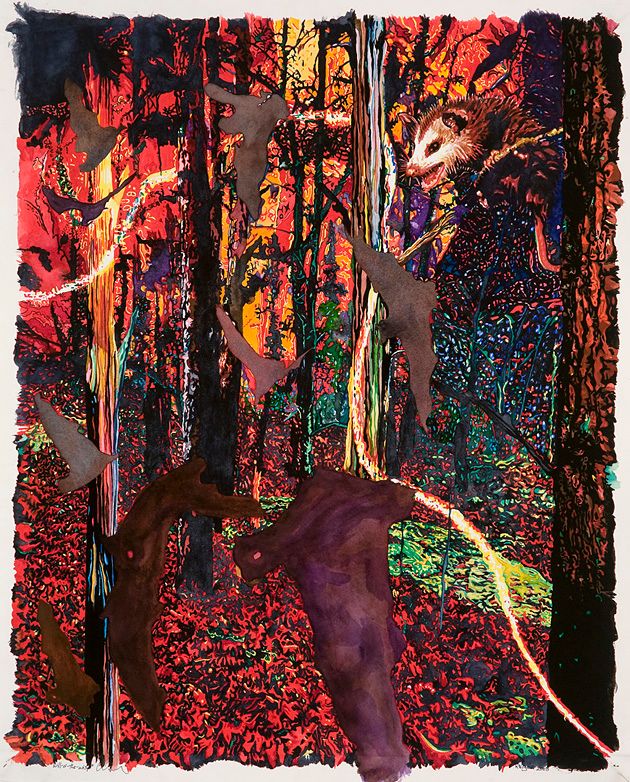

Christopher Reiger

"will-o'-the-wisp"

2008

Watercolor, gouache, sumi ink and marker on Arches paper

27 x 22 inches

I have two exhibition receptions in New York this coming week, an opening at Denise Bibro Gallery on Thursday, September 4th, and a closing at Dieu Donne Papermill on Friday, September 5th.

I'm particularly excited about "Animus Botanica," the 3-person show at Denise Bibro. I'm including twenty drawings and four recent paintings (one of which is pictured above), and sharing the bill with two friends and talented artists, Amy Ross and Boyce Cummings. (Check out Amy's blog here.)

The Dieu Donne Papermill exhibition, "Opportunity as Community, Part Two," is also excellent, of course, and not on view for much longer.

Come on out and say "Hi." I'll be at both receptions, and so will my parents, trekking north from Virginia for the two-fer!

Please find further details for both exhibitions below.

+++++

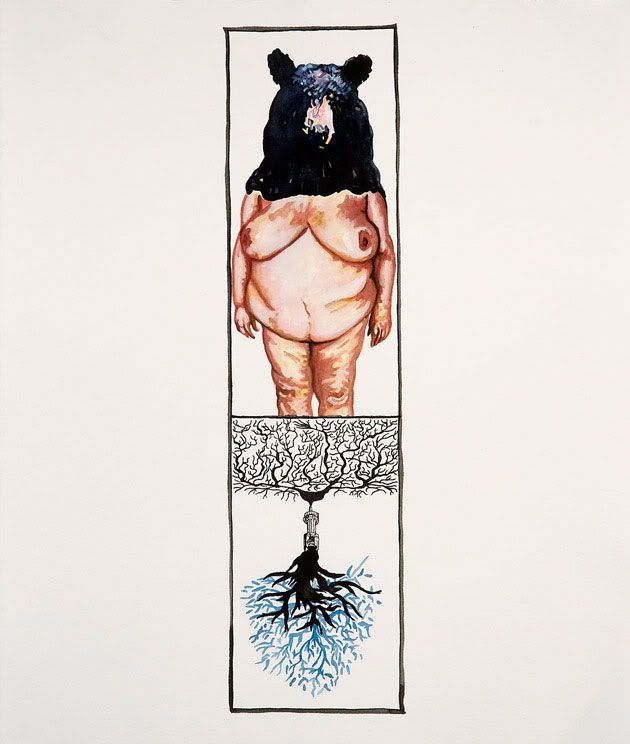

Christopher Reiger

"Forgotten Blood Roots #1"

2008

Pen and ink, sumi ink, gouache and watercolor on Arches paper

17 1/2 x 14 3/4 inches

Denise Bibro Fine Art

"Animus Botanica: Boyce Cummings, Christopher Reiger & Amy Ross"

September 4th - October 4th, 2008

529 West 20th Street 4W

New York, NY 10011

(212)647-7030

Gallery hours: Tuesday-Saturday, 11AM - 6PM

Artists' Reception: Thursday, September 4th, 6-8PM

Exhibition press release:

In "Animus Botanica," three young artists explore themes of nature, narrative, and fantasy. On view September 4 through October 4, 2008, the work of Boyce Cummings, Christopher Reiger, and Amy Ross encompasses painting, drawing, and collage. The subject matter centers on flora, fauna, and the human form, as well as hybrid creatures, all of which are enthralling, and sometimes downright ominous. A fox emerges from the soft pink petals of a magnolia blossom, a Rubenesque female figure sports a bear's head, an opossum bears his teeth against an onslaught of bats, a lifeless bird hangs from string amongst a botanical rendering.

According to painter Boyce Cummings, nature occupies a large part of his inner life, and he casts people as animals in his works in oil, acrylic, and mixed media. Birds preside over seemingly abandoned architectural structures in barren landscapes, an abstract curvilinear design decorated with stars become the bird's lonely song. A regal polar bear silently crosses a white abyss, while an underpainting reveals numerous caricature portraits, recalling the disturbing drawings created to illustrate phrenology, or the study of the shape of the human head as it was thought to relate to intelligence.

Christopher Reiger's complex multi-media paintings on paper vibrate with saturated color and dense compositions of fauna, which the artist refers to as "hallucinatory landscapes." Often populated by menacing crows and other intimidating animals, Reiger suggests that nature is by no means idyllic, and compares its extremism to the contemporary cultural and political climate. His smaller works on paper allude to man's mutable conception of nature, while at the same time referencing archaic scientific experiments involving humans, animals, and plants.

Amy Ross' watercolors and collages portray delicate, elegantly rendered botanicals morphed with animal and human forms. Ross notes these images subvert the traditional genre of botanical illustration by viewing the natural world through the lens of genetic engineering and mutation gone awry. Woodpeckers with mushroom caps for heads adorn fragile white birch branches; another mushroom sprouts into a headless, writhing serpent. While these creatures are charming, Ross alludes to the dangers of meddling with nature.

Cummings, Reiger, and Ross all have extensive exhibition histories. To view their resumes, please visit our website. For more information, or high resolution images, please contact the gallery.

+++++

Christopher Reiger

"More of the Less That Is Left #2"

2008

Handmade paper, shellac ink, sumi ink, thread, archival glue and hanger

38 x 15 inches

Dieu Donne Papermill

"Opportunity as Community: Artists Select Artists, Part Two"

August 1st - September 6th

315 West 36th Street

New York, NY 10018

(212)226-0573

Gallery hours: Monday - Friday, 10 - 6 PM

Closing reception: Friday, September 5th, 6 - 8 PM

Participating artists:

Louis Cameron (selected by Mary Temple)

Sarah Crowner (selected by Peter Simensky)

Bruce Dow (selected by Allyson Strafella)

Marc Handelman (selected by Vargas-Suarez Universal)

Karl Jensen (selected by Brad Brown)

Joan Linder (selected by Sonya Blesofsky)

Liza McConnell (selected by Kirsten Hassenfeld)

Mike Quinn (selected by Rachel Foullon)

Christopher Reiger (selected by A.J. Bocchino)

+++++

Also, "Year of the Rat" continues to run at Archibald Arts. Steal a peak at my inclusion here. Stop by if you get a chance!

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)