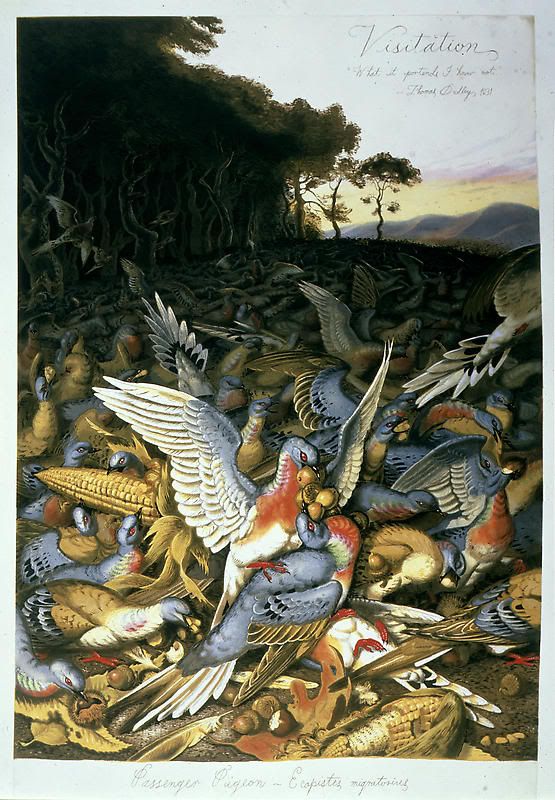

"The Prophet Amos"

1891

Engraving

In the Hebrew Tanakh, the colorful collection of history, anthropology, and mythology better known to Christians as the Old Testament, a number of the prominent prophets decry the institutionalization of Israelite religion. Elijah, Amos, Hosea, Isaiah, and Jeremiah proclaim instead the communal and, in some cases, individual experience of the one, true God. They maintain that God can be best experienced (and, as the ancient Israelites believed, best appeased) through one's devotion to those moral laws, or mitzvot, concerned with righteousness and social justice. These courageous and outspoken men also possess an enmity for the organized priesthood. They insist that the Israelites needn't centralize their worship at Solomon's Temple in Jerusalem, or at any of the other state worship shrines constructed within the kingdoms of Israel and Judah."Let justice roll down like waters, and righteousness like an ever-flowing stream."

-Amos 5:24

Not surprisingly, excepting the rare case when a prophet's ideology was deemed politically expedient, Israelite state leaders frowned on religious populism and the theocracy ignored the prophet's pleas. Typically, the trouble-making prophets were ostracized, expelled, or hunted as fugitives. Yet, ultimately, the prophets' voices proved appropriately prophetic.

For most of their history, Jews have lived in diaspora, their religious faith and identity rooted in a universalist foundation of scripture, theory, and law rather than any centralized site or body. In fact, most contemporary religious historians believe that the flowering of the relatively archaic and essentially polytheistic Israelite religion into Judaism follows the fall of Jerusalem to the Babylonians, in 587 BCE, and that this early, exilic manifestation of Judaism would undergo another upheaval and transformation after the destruction of the Second Temple by the Romans, in 70 CE. In essence, these scholars suggest that the Israelites (and, later, the Jews) had to forgo state power before the moral idealism of their religion could be actualized.

Accordingly, then, the muscular, modern state of Israel poses challenges to Jewish moral idealism. But contemporary Israeli Jews aren't alone in their wrestling with this challenge. Almost 2,500 years after the Hebrew prophets condemned top-down involvement in spiritual matters, liberal-minded, religious individuals of all stripes continue to struggle against blindly restrictive doctrinal authority.

I do not intend to suggest that adherence to dogma is necessarily a bad thing. Moral hand-wringing is a natural component of ethical decision-making, and traditional values of the sort upheld by religious authorities offer each of us a valuable point of reference. But what of contemporary conflicts between religious action and the religious institution? What of those cases in which the civil and moral codes of a religion suggest that the adherent to those codes should act in some way other than that dictated by the religious institution?

Laura Goodstein's recent New York Times article, "U.S. Nuns Facing Vatican Scrutiny" provides an excellent example. Goodstein writes,

"In the last four decades since the reforms of the Second Vatican Council, many American nuns stopped wearing religious habits, left convents to live independently and went into new lines of work: academia and other professions, social and political advocacy and grass-roots organizations that serve the poor or promote spirituality. A few nuns have also been active in organizations that advocate changes in the church like ordaining women and married men as priests."What could possibly be wrong with nuns advocating for progressive social change!? While I respect those individuals who dedicate their life to religious contemplation, aren't the monks and nuns that work for God outside of monastery and convent walls the most exemplary of all religious adherents? Aren't those individuals striving for Thomas Merton's brand of religiously-inspired activism representative of the 13th century theologian and mystic Meister Eckhart's call for believers to "gratefully [return] all that God has bestowed [...] and, by that act of donation, enter the Godhead"? In the eyes of the Vatican, apparently not.

"The investigation was ordered by Cardinal Franc Rodé, head of the Vatican office that deals with religious orders. In a speech in Massachusetts last year, Cardinal Rodé offered barbed criticism of some American nuns 'who have opted for ways that take them outside' the church. [...] The [Vatcian's investigation] focuses only on nuns actively engaged in working in society and the church, not cloistered, contemplative nuns."If the Vatican has spearheaded the investigation only because the Church seeks confirmation that American activist nuns are "attending Mass and keeping the sacraments," all well and good. After all, attending Mass and keeping the sacraments are obligations of religiously observant Catholics, and an individual who has devoted his or her life to the church should certainly be upholding these traditions. If, however, the Church intends to castigate or defrock otherwise devout, responsible nuns for pursuing religious behavior outside of the church, the Vatican officials should be ashamed of themselves.

As the Catholic theologian Walter Brueggemann wrote in The Prophetic Imagination, "The task of prophetic ministry is to nurture, nourish, and evoke a consciousness and perception alternative to the consciousness and perception of the dominant culture around us." For the Catholic nuns, as for the Hebrew prophets millennia before them, the dominant culture is that of their respective religious institutions, one of staid and comfortable orthodoxy. I'm not a Christian, but were I one, and especially if I were Catholic, I would be up in arms over the Vatican's sanctimonious oppression of those exceptional nuns and monks who actually paid attention to the substance of Jesus of Nazareth's memo.

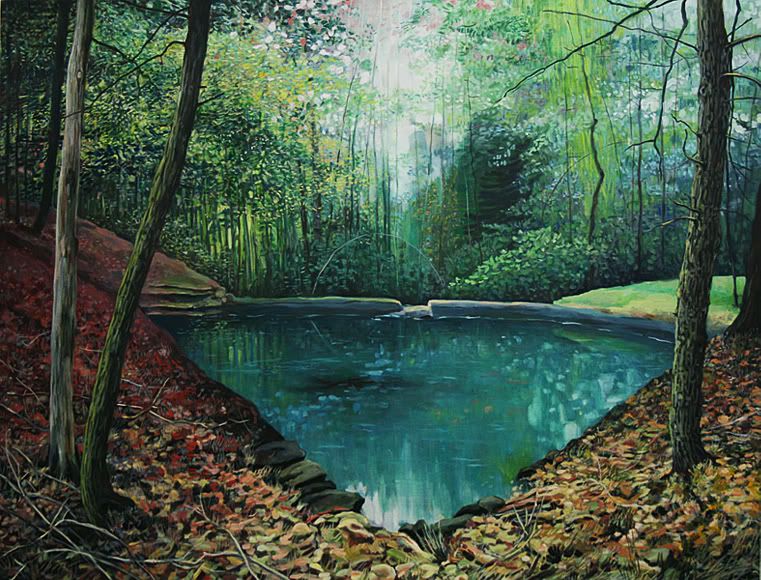

Photo credit: ripped from Wikipedia