On the whole, I've been rather hopeful for the last two years. But perhaps it was naive of me to believe that the

First World was at last recognizing the western model of political and economic "progress" as an undemocratic, globalized burden? Is it not clear that

super-capitalism punishes, starves and buries the less fortunate "lower" classes along with the "lesser" species? Do the present-day "winners" not understand that, eventually, when the structural interior is rotted out, the upper echelon will come crashing down?

A friend gave me a copy of the

Time Magazine Style & Design Supplement last week. I wish that I hadn't read it; the supplement's articles have only contributed to my intensifying skepticism of and despair for the art market.

Consider, for example, Karen Katz, Neva Hall, and Ann Stordahl, so-called "power players" at

Neiman Marcus. Kristina Zimbalist, one of the supplement's writers, calls the three women "Magical Thinkers" because they've "orchestrated America's current luxury boom, lifting the consumer ever higher."

"And the world is primed for what Neiman Marcus president and CEO Katz calls 'high luxury'; the number of households worth more than $5 million is greater than ever before...'It's even more luxurious, more unique, harder to get. We want to sit at the top of the luxury mountain,' [Katz] says. 'We're pushing higher, to find that even rarer air.'"

The attitudes of people like Katz are irredeemable...and awfully depressing.

Publications like the

Time Style & Design Supplement prove my optimism misguided; we are not yet recognizing the gravity of our trespasses. Even as wealthy dilettantes bemoan

the tenuous station of the polar bear, they celebrate news of the "Global Luxury Survey: China, India, Russia," another article included in the

Time supplement.

"Ask any seasoned luxury-goods executives what excites them most about the future of the category, and they will undoubtedly launch into a lengthy discourse on emerging markets. For some, China holds the most promise, with its double-digit yearly growth and the expectation that it will surpass the U.S. in luxury-goods consumption by 2015...In this, the first installment of a four-part series, Time measures the affluent consumer's appetite for luxury brands in these exciting markets."

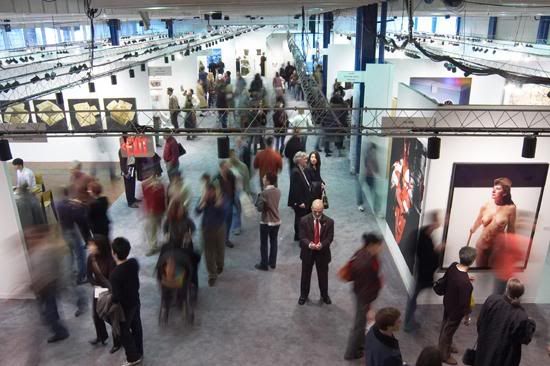

China? Russia? Regular readers of

ArtNews and other industry glossies know that these "market opportunities" aren't far from the minds of art world movers and shakers. The art world is, after all, just another arm of the global luxury market.

When

Edward Winkleman argued recently, in his post, "

Blinded by Blood Lust," that good art can coexist with a strong market, I didn't find fault with his assertion. Yet I'm troubled by the pain that radiates outward from a thriving market. Dealers and artists may not be directly assaulting the environment or the poverty stricken, but they're happily trading in bloody money, and all the while identifying themselves as "liberal," "progressive" and "caring."

As Edward contends, the "art market death watch cheerleaders" - I include myself in their ranks - are deluded if they cheer because they believe that "we'd have better or more interesting art if only" the market collapsed. I hope that most of them, like me, are instead cheering for change (for alternatives). The thriving art market is one more indication that our species, propelled by the west's thoughtless economic imperatives, is in a frightening position, every bit as tenuous as that of brother polar bear.

A successful man that I know, someone affiliated with the art world, recently purchased a watch for $11,500. This acquisition disturbs me for two reasons. First, even a limited awareness of the social and ecological ravages of luxury markets should discourage an educated individual from making such a purchase. Second, I was forced to acknowledge that his buying the watch is essentially no different from his buying a painting.

The watch wasn't

encrusted with diamonds; outwardly, it didn't even look particularly expensive. If you didn't know

the brand, you'd likely mistake it for an inexpensive model and make. It's a status symbol and, as such, is designed to be recognized only by other people of status. Considering the watch, I concluded that it (like the bought-and-sold artworks in Chelsea) is an artifact of contemporary "high luxury," a branded investment that is

grafted to the market, useful only as a wealth signifier.

Daniel Quinn's allegory of the airman, taken from his renowned novel "

Ishmael," is pertinent to this discussion. Our civilization knows well that the laws of aerodynamics, physical realities that we had to identify in order to construct serviceable planes and helicopters,

don't defy gravity. Quinn writes,

"There is no escaping [gravity], but there is a way of achieving the equivalent of flight - the equivalent of freedom of the air. In other words, it is possible to build a civilization that flies."

But before we understood aerodynamics, would be aviators built "pedal-driven contraptions with flapping wings, based on a mistaken understanding of avian flight."

"As the flight begins, all is well. Our would-be airman has been pushed off the edge of the cliff and is pedaling away, and the wings of his craft are flapping like crazy. He's feeling wonderful, ecstatic. He's experiencing the freedom of the air. What he doesn't realize, however, if that this craft is aerodynamically incapable of flight. It simply isn't in compliance with the laws that make flight possible - but he would laugh if you told him this. He's never heard of such laws, knows nothing about them. He would point at those flapping wings and say, 'See? Just like a bird!' Nevertheless, whatever he thinks, he's not in flight. He's an unsupported object falling toward the center of the earth...in free fall.

Fortunately - or, rather, unfortunately for our airman, he chose a very high cliff to launch his craft from. His disillusionment is a long way off in time and space...There he is in free fall, experiencing the exhilaration of what he takes to be flight...However, looking down into the valley has brought something else to his attention. He doesn't seem to be maintaining his altitude. In fact, the earth seems to be rising up toward him. Well, he's not very worried about that. After all, his flight has been a complete success up to now, and there's no reason why it shouldn't go on being a success. He just has to pedal a little harder, that's all."

As the extremes of wealth and poverty continue to grow at home and abroad, we point to our contraption's flapping wings, grin madly and pedal away.

The

Time supplement tells readers that Russia's growing millionaire class has "[forgotten] about stealth wealth. The Russia luxury consumer wants to flaunt economic status." Of course they do. As the globe's upper 5% becomes increasingly burdened by a concentration of wealth, they will begin to in-fight, one-upping one another in ostentatious displays. The rest of us will suffer for it; governments will be bought and sold and human rights will be tread upon. So long as western culture continues to celebrate the individual over community, the economic pilots can keep pointing at their flapping wings...at least until we all slam into the valley floor.

Today, however, there seem to be more intrepid, deluded airmen than ever before. Priya Tanna, editor of

Indian Vogue proudly relates the news: "At a very micro level, I think every Indian woman who is now financially independent is realizing the joys of guilt-free consumption. We are kind of moving from a 'we' culture to a 'me' culture." Oy, vey!

Why, then, am I a "death watch cheerleader"? Because no other species has acted this irresponsibly and survived. We are pushing the limits of natural law. I don't know if the poisonous labors of our hubris can be mended, but each of us, as citizens and moral animals, needs to make some significant, individual choices that will spill over, one hopes, into a renewed sense of community. For artists, these choices must affect how they eke out a living, and what sort of creative dialogue they are willing to participate in.

Again, I'm hoping to engender some sort of discussion about these ideas. I don't have any solutions jotted down.

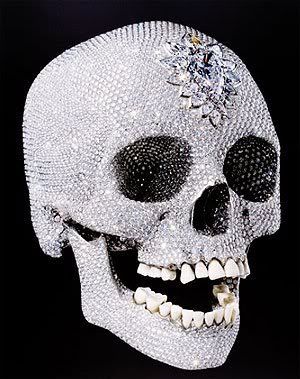

Photo credit: unattributed picture of

Damien Hirst's "For The Love of God"