Several months ago, I read "The Problem With Human Compassion," an excerpt from Shankar Vedantam's book The Hidden Brain, printed in the February 19th issue of The Week. I include a lengthy selection here.

"On March 13, 2002, a fire broke out in the engine room of an oil tanker about 800 miles south of Hawaii. The fire moved so fast that the Taiwanese crew did not have time to radio for help. Eleven survivors and the captain’s dog, a terrier named Hokget, retreated to the tanker’s forward quarters with supplies of food and water.Vedantam and Singer are correct; we humans act more compassionately when we are able to put a face to a cause, yet too many faces dull our response.

[...] Drawn by wind and currents, the Insiko got within 220 miles of Hawaii. It was spotted by a cruise ship, which rescued the crew. But as the cruise ship pulled away, a few passengers heard the sound of barking.

The captain’s dog had been left behind on the tanker. A passenger who heard the barking dog called the Hawaiian Humane Society in Honolulu. [...] The Society alerted fishing boats about the lost tanker and soon media reports began appearing about Hokget.

[...] Money poured in to fund a rescue. Donations eventually arrived from 39 states and four foreign countries. One check was for $5,000. 'It was just about a dog,' Pamela Burns, president of the Hawaiian Humane Society, told me. 'This was an opportunity for people to feel good about rescuing a dog. People poured out their support. A handful of people were incensed. These people said, ‘You should be giving money to the homeless.’' But Burns thought the great thing about America was that people were free to give money to whatever cause they cared about, and people cared about Hokget.

The problem with a rescue was that no one knew where the Insiko was. The U.S. Coast Guard estimated it could be anywhere in an area measuring 360,000 square miles. Two Humane Society officers set off into the Pacific on a tugboat. The Society paid $48,000 to a private company called American Marine to look for the ship.

[...] The U.S. Coast Guard had said it could not use taxpayer money to save the dog, but under the guise of training exercises, the called the U.S. Navy began quietly hunting for the Insiko.

[...] Human beings from around the world came together to try to save a dog. The vast majority of people who sent in money would never personally see Hokget. It was, as Pamela Burns suggested to me, an act of pure altruism and a marker of the remarkable capacity human beings have to empathize with the plight of others.

There are a series of disturbing questions, however: Eight years before the Hokget saga began, the same world that showed extraordinary compassion for a dog sat on its hands as hundreds of thousands of human beings were killed in the Rwandan genocide.

The philosopher Peter Singer once devised a dilemma that highlights a central contradiction in our moral reasoning. If you see a child drowning in a pond—and you would ruin a fine pair of shoes worth $200 if you jumped into the water—would you save the child or save your shoes? Most people react incredulously to the question; obviously, a child’s life is worth more than a pair of shoes. But if this is the case, Singer asked, why do large numbers of people hesitate to write checks for $200 to a reputable charity that could save the life of a child halfway around the world—when there are millions of children who need our help?

The answer is that our moral responsibilities feel different in these situations; one situation feels visceral, the other abstract. We feel personally responsible for one child, whereas the other is one of millions who need help - there are many people who could write that check.

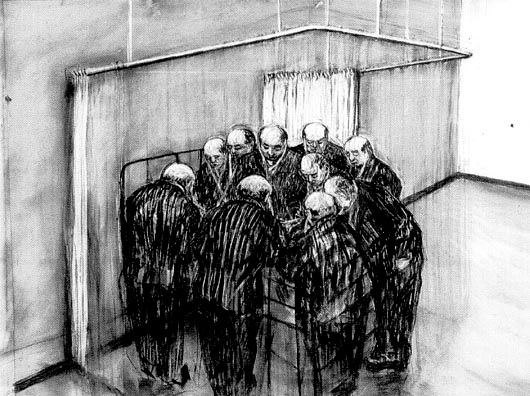

[...] The brain is simply not very good at grasping the implications of mass suffering. Americans would be far more likely to step forward if only a few people were suffering or a single person were in pain. Hokget did not draw our sympathies because we care more about dogs than people; she drew our sympathies because she was a single dog lost on the biggest ocean in the world. [...] We are best able to respond when we are focused on a single victim."

I've noticed such a benumbing in myself recently, an unexpected consequence of my transitioning from New York City to San Francisco. Both cities have substantial homeless populations, but panhandling in San Francisco is far more common. My street charity policy, modeled on the approach of a rabbi I heard lecture, is simple enough: I give change to any panhandler who says that he or she will use the money for food (or cites hunger as their reason for begging). I don't give change to those individuals requesting money for any other reason. In New York City, confronted with a few beggars each day, I typically gave change two or three times every week. In San Francisco, however, beggars ask for handouts on every other block, and a good number of them say that they're hungry. If I hold to my standard, I'll give change two or three times a day, if not more often! Shamefully, I've noticed that I've almost ceased giving during my visits to San Francisco.

This is a personal failure that I must address. Each of those many faces is an individual, a single person in need, despite the fact that their larger numbers and concentration counter-intuitively make them relatively anonymous or invisible. The rabbi's rule should be no less applicable in San Francisco than it is in New York. I'm confronted, then, with more need, and I must respond in kind; a hungry person is a hungry person.

But what about a hungry dog? Is Vedantam right to suggest that the thousands of people who contributed money to the Hokget search did not "care more about dogs than people"? Not exactly.

Our species' evolved, inborn behaviors haven't made our adaptation to the globalized world easy. In fact, it seems that contemporary humans are increasingly suspicious of other humans, especially of those outside our respective tribe, whereas animals (and perhaps especially dogs) are seen as uncomprehending innocents. I don't mean to suggest that no one cares about miners trapped in a coal mine, but it's clear that the little girl trapped in a well sells more newspapers, and that the little dog trapped on an abandoned tanker not only sells newpapers, but also inspires a flood of unsolicited donations and generates public outcry.

"Facing intense public pressure to save Hokget, government officials concluded that asking the Navy to sink the tanker—750 miles from Hawaii and drifting away from the distant U.S. mainland—posed unacceptable environmental risks. The Coast Guard finally agreed to access $250,000 in U.S. taxpayer funds to recover the Insiko. It wasn’t officially called an animal-rescue effort. Instead it was authorized under the Oil Spill Liability Trust Fund, based on the argument that if the aimless Insiko managed to drift westward for 250 straight miles, it might run aground on Johnston Atoll and harm marine life.What a marvelously strange species we are!? I applaud our ability to extend compassion to other animals (we're one of handful of species that have demonstrated such empathic ability), but I wonder at our brains' curious moral calculus.

[...] On April 26, nearly a month and a half after the dog’s ordeal began, the tugboat’s crew found the Insiko and boarded the tanker. Hokget was still alive, hiding in a pile of tires. [...] Hokget arrived in Honolulu on May 2 and was greeted by crowds of spectators, a news conference, banners welcoming her to America, and a red Hawaiian lei."

I suppose all I can do is begin with myself, and humbly pledge to keep my pockets filled with coins.

Image credit: ripped from Corbis Images