I enjoyed reading "

The Boom Is Over. Long Live the Art!," Holland Cotter's sometimes scathing

New York Times farewell to contemporary art's reckless past decade. Cotter describes the art world as a "full-service marketing industry [built] on the corporate model," and he sees art schools as a branch of this money-hungry industry. In his estimation, critics, curators and other art world operators are "public relations specialists who provide timely updates on what desirable means." With these stark observations in mind, Cotter asserts that "a financial scouring can only be good for American art."

"The Boom Is Over" likely raised the ire of many artists and dealers. A commenter on

Edward Winkleman's blog characterized Cotter as "out of touch" and guilty of perpetuating a "fabled myth," and I wouldn't be surprised if more online dismissals and condemnations of Cotter's article appear in coming days. That's a shame. I don't believe that the article is intended to titillate or to offend.

Cotter's description of our prodigal art world brings to mind artist and critic

Robert Morgan's caution not to mistake glamour for substantive beauty.

"Beauty is not glamour. Most of what the...art world has to offer is glamour. Glamour, like the art world itself, is a highly fickle and commercially driven enterprise that contributes to...the 'humdrum.' It appears and disappears...No one ever catches up to glamour."

Because I call on Morgan's rather romantic position, some readers will immediately decide that, like Cotter, I'm guilty of perpetuating a myth. If so, it is a vital myth. The beauty that Morgan exalts is complicated and profound. I have in mind philosopher poet

John O'Donohue's conception of beauty.

"Beauty induces atmosphere and spirit: wonder, delicious turbulence, love, longing and a trembling delight....Beauty inhabits the cutting edge of creativity - mediating between the known and the unknown, light and darkness, masculine and feminine, visible and invisible, chaos and meaning, sound and silence, self and others."

O'Donohue defines a soulful beauty, a beauty that springs from generous attempts to be and to belong.

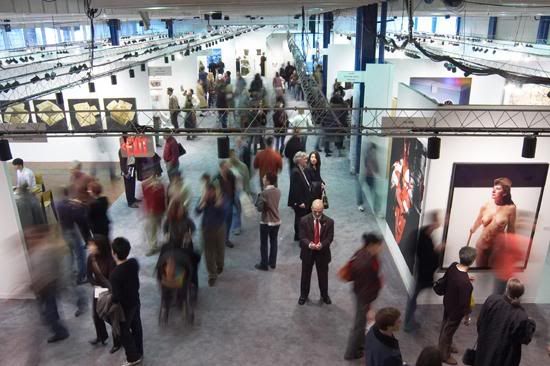

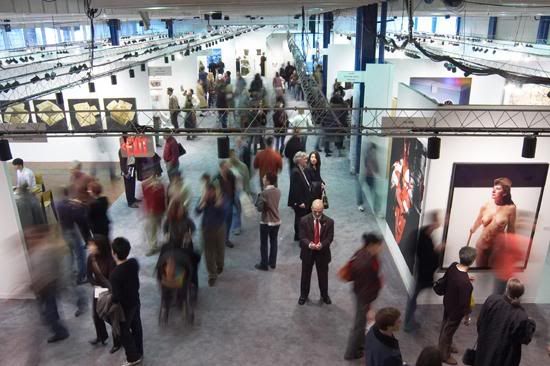

Although many of the artworks offered for sale at art fairs or on auction blocks are born of beautiful striving, art fairs and auctions are never, themselves, beautiful. And because fairs and auctions are the events most representative of the contemporary art world, Cotter's harsh language seems reasonable. He's right; "during the present decade [art] has become a diminished thing."

I sense that Cotter wants the

Times article, a dismal record of a profligate art world, to serve as license for artists, dealers, curators and critics (Cotter's own tribe) to ruminate on their standing. He hopes that the result of that rumination would be an open-hearted embrace of the artist's vital social role (and the art world's part in facilitating that). It is edification, above all, that interests Cotter.

"With markets uncertain, possibly nonexistent, why not relax this mode, open up education? Why not make studio training an interdisciplinary experience, crossing over into sociology, anthropology, psychology, philosophy, poetry and theology? Why not build into your graduate program a work-study semester that takes students out of the art world entirely and places them in hospitals, schools and prisons, sometimes in in-extremis environments, i.e. real life?...Such changes would require new ways of thinking and writing about art, so critics would need to go back to school, miss a few parties and hit the books and the Internet....[If] there is a crisis, it is not a crisis of power; it's a crisis of knowledge. Simply put, we don't know enough..."

Amen.

But I think that Cotter should have included an addendum. Speaking in generalities can be valuable, but the excess and superficiality of the art world's recent history hasn't tainted

all artists, dealers, curators and critics. Certainly, there are "thousands of groomed-for-success [art school] graduates" who have made contemporary art into something "proliferating but languishing," but there are also, as ever, many individuals pushing toward O'Donohue's complicated beauty. Some admirable artists and dealers experienced great success in the boom market of the late nineties and oughties. Perhaps they wouldn't have flourished without the opportunities afforded them by the fattened industry? Artists have always had an uneasy relationship with commodity, and there's little sense in championing lean times over relative abundance.

We're now living through an socio-economic upheaval that is quite nearly global. Such rapid and widespread change should, as Cotter expects, force a significant number of artists to conscientiously reexamine their ideals. But let's not delude ourselves. The opportunity for reflection and mindful action wasn't precluded by the excesses and superficialities of boom time. Although some artists, dealers, curators, critics and hangers-on acted improperly because the environment encouraged bad behavior, most did so because they

wanted to. So even as I cheer Cotter's call for us to "[imagine] the unknown and the unknowable," to raise up "new ways of thinking and writing about art," and to see artists blazing unexpected paths, I remind myself that the burden of proof falls foremost on the individual.

Image credit: ripped from

Daily Serving