"Windwalk #2 - Charing Cross"

Helmet

2008

For his "Windwalk - 5 Walks from Charing Cross" project, artist Tim Knowles engineered a helmet with a sail-like wind vane, small video camera and GPS device, then wandered the streets of central London, his path determined solely by the wind. As Knowles crosses major thoroughfares, where the wind enters the wider channel via various tributaries, his path hitches and tacks erratically. If a gust of wind blows from the opposite direction, he spins about face, and he sometimes circles upon an earlier position.

In at least two of the videos that document his wind walks, Knowles is led into a cul de sac of swirling wind, where he finds himself temporarily trapped with light-weight street debris, including plastic bags and leaves. In these situations, or when he is directed into a wall, Knowles waits patiently for the wind to change direction and again grant him headway.

The artist Bernard Buffet wrote, "I prevent myself from thinking in order to be able to live." Although Buffet presumably referred to the particularly European struggle to persevere in a world shadowed by acute suffering and inhumane activity (he made the declaration in 1948, after an adolescence in occupied France), the statement can also be understood as an endorsement of Zen's "mind of no mind," or mushin no shin. Regardless of their geographic or religious provenance, meditative practices commonly encourage practitioners to banish thought from the mind so that they might experience transcendence or some heightened sense of being.

Similarly, the 20th century aesthetic theorists Alfred North Whitehead and John Dewey believed that there is a crucial distinction between the aesthetic and rational realms. Dewey argued that the aesthetic province is that of the "live animal" or unmediated, natural experience. In his landmark book Art As Experience, Dewey writes,

"Life goes on in an environment; not merely in it but because of it, through interaction with it. No creature lives merely under the skin; its subcutaneous organs are means of connection with what lies beyond its bodily frame, and to which, in order to live, it must adjust itself, by accommodation and defense but also by conquest. At every moment, the living creature is exposed to dangers from its surroundings, and at every moment, it must draw upon something in its surroundings to satisfy its needs. The career and destiny of a living being are bound up with its interchanges with its environment, not externally but in the most intimate way."Elsewhere, Dewey states more plainly, "to grasp the sources of aesthetic experience it is necessary to have recourse to animal life below the human scale." The life Dewey describes, the realm of the "live animal" and of true aesthetic experience, is akin to Zen's mushin no shin.

The late Irish philosopher and poet John O'Donohue described dance as a reclamation of our animal nature. He wrote,

"When you walk into the mood of wind, it cleanses your mind and invigorates your body. It feels as if the wind would love you to dance...The body gives itself away playfully to the rhythm of the music; the burden of consciousness becomes suspended. For a while the innocence of the dance claims you completely as the mind relents and the body becomes its own celebration."Knowles' "Windwalks" allow him access to the realm of Dewey's "live animal" and of O'Donohue's celebratory body; the artist relinquishes control by bypassing the brain's self-conscious helmsman. The wind meanders London's streets and Knowles follows; if he is the dancer, the wind is his choreographer. The artist is compelled by the wind's whim.

But, in allowing himself to be guided by an external force, Knowles doesn't simply provide viewers with an often humorous and poetic take on Dewey's philosophy of essential aesthetic experience. His "Wind Walks" resonate on several levels, and perhaps the most vital subtext is one of openness to new experience and new ideas.

Knowles provides us with a 21st century model of citizenship. He explores Charing Cross in a novel way; in doing so, he is provided with a fundamentally new appreciation for and knowledge of a seemingly familiar London neighborhood. In our rapidly globalizing world, we'd do well to emulate Knowles' willingness to look again for the first time. As T.S. Eliot wrote in his poem "Little Gidding,"

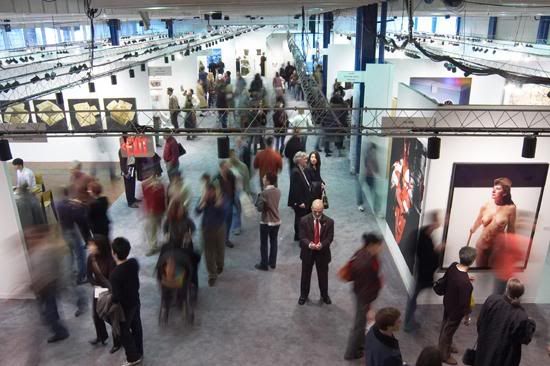

"We shall not cease from exploration"Windwalk - 5 Walks from Charing Cross" was seen in the Bitforms Gallery exhibition, "Tim Knowles and Pe Lang + Zimoun: Unpredictable Forms of Sound and Motion," recently on view in New York City.

And the end of all our exploring

Will be to arrive where we started

And know the place for the first time."

Photo credits: images ripped from The Cyborg's Picnic and VVVORK