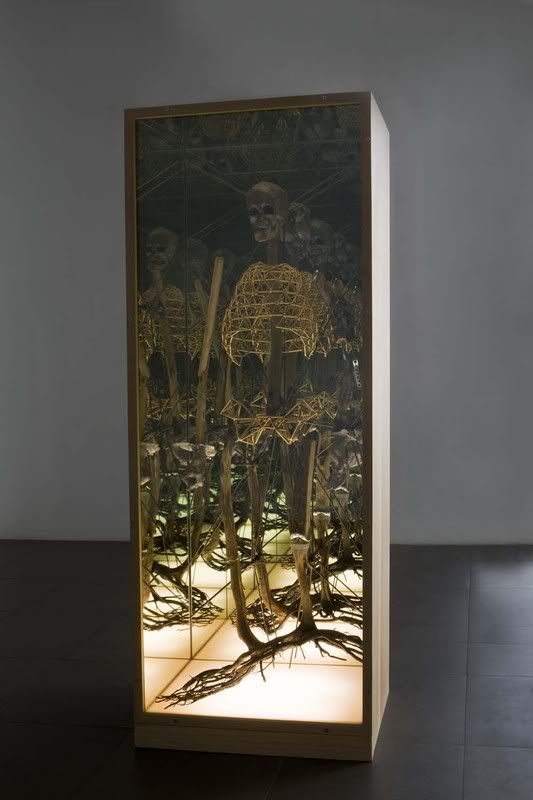

Installation shot of Matthew Day Jackson's "Terranaut," at Peter Blum, Chelsea

Courtesy of Peter Blum Gallery, New York

but for want of wonder."

-J.B.S. Haldane

On the drizzly Wednesday evening past, I attended a ScienceBlogs panel at the SoHo Apple Store. ScienceBlogs bills itself as "a portal to...global dialogue, a digital salon featuring the leading bloggers from a wide array of scientific disciplines." I'm familiar with a number of the blogs hosted by the network; among them is one of my regular blogosphere stops, Bioephemera. Jessica Palmer, the writer, artist and scientist behind Bioephemera, participated in the panel, and I attended with lofty expectations. Unfortunately, the panelists were unable to delve deeply into any of the subjects that most excite them. Instead, they answered humdrum questions that ranged from 'How often do you upload new material?' to 'What was your most popular or controversial post?' (Generally, their responses were similarly unexciting, but they delivered them earnestly and with good humor.)

Addressing that second question, one panelist mentioned the popularity of Pharyngula, a blog written by evolutionary biologist P.Z. Myers. Every day, Myers' blog receives a great many visits, but a sizable minority (perhaps even the majority) of those visitors are religious fundamentalists, Creationists who beset the blog with nasty comments about Myers and the ideas he expounds. In fact, Myers has posted an ever-lengthening list of undesirables, readers now banned from Pharyngula's comment section.

It's no secret that evolutionary biologists and Creationists don't break bread together. Their enmity has a storied history. Yet many people understand the dispute to be more broad, as a fracas between scientists and the religious community at large. And it is not only bystanders that see it this way. Some scientists lend credence to the misconception by assuming that all religious individuals are skeptical of evolutionary biology, in particular, and, more generally, of science as a whole. This simply isn't true. The science/religion dichotomy is false. Only the ignorant, the unimaginative, the misguided or some combination thereof embrace religious fundamentalism, and among the ranks of the religious, there are countless educated, creative and thoughtful individuals. Within this latter group, science and evolution are accepted, even championed.

At their respective best, both science and religion (re)awaken or invigorate our capacity for wonder. Each makes use of a different approach, but they are complementary. As Albert Einstein famously said, "Science without religion is lame. Religion without science is blind." The late evolutionary biologist Stephen Jay Gould called the two "nonoverlapping magisteria" because good science trades in facts to explain material phenomena, whereas religion traffics in the unverifiable and the unobservable. Where science seeks to demystify, and to build on each subsequent revelation to learn more, religion aims to make sacred that which is taken for granted, to make the ordinary again extraordinary. Both, however, offer frameworks of engaging our astonishing existence and experience. Both are compelled by curiosity and wonder. As Gotthold Ephraim Lessing, the Enlightenment writer-philosopher, argued, if God held in one hand the Entire Truth and in the other the Eternal Pursuit of Truth, a good man will choose the latter. The same is true of authentic scientists and religious thinkers. The methodology and particulars may differ, but both science and religion are realms of the question. Although the popular conception of the scientist is the white-coated statistician ready to provide any and all answers, the caricature is misleading. It is "normative in science to be not sure," as Jessica Palmer put it doing the ScienceBlogs panel. Science, like religion, is a matryosha doll, a series of questions nested within questions.

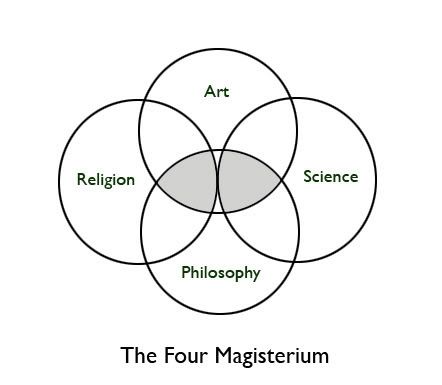

Gould considered art and philosophy magisteria unto themselves, but, unlike religion and science, each overlaps the other. Where these two overlapping sections meet, we find ourselves in the realm of what the artist-writer Paul Laffoley calls the mesoteric. In Laffoley's cosmology, the circle of religion, dealing as it does with questions of ultimate meaning, is dubbed the esoteric realm. The circle of science, focused on material truths and the observable world, he labels the exoteric realm. The mesoteric realms. art and philosophy, bridge the esoteric and exoteric. Whereas Gould posits that the magisteria of religion and science are nonoverlapping, I would argue that, where their circles meet, the membrane is permeable. This bleeding of one into the other represents the pinnacle of art and philosophy.

Matthew Day Jackson

"Dymaxion Skeleton"

2008

Wood, lead, Plexi-glas, light, glass mirror, steel

86 x 33 x 22 inches

Courtesy of Peter Blum Gallery, New York

Because Matthew Day Jackson's sculptures draw from this leak, inspired by (and responding to) both science and religion, the very best are imbued with (and exude) hope, curiosity and wonder. Two sculptures, "Dymaxion Skeleton" and "Against the Mythology of Linearity," both included in "Terranaut," Jackson's current exhibition at Peter Blum Gallery, are exceptional artifacts (literally, artful fact), notable for their humor, evocative power and awe-struck humility.

Presented within an illuminated, birch-paneled vitrine, "Dymaxion Skeleton" is a piece-meal assembly: the feet of this skeleton are tree roots; the legs, arms and spine are branches; the rib-cage and pelvis are geodesic triangle lattices (hence the Buckminster Fuller allusion in the work's title). To the guileless viewer, the skeleton could pass for a loan from the American Museum of Natural History, a relic of some lost people, but "Dymaxion" is no archaeological discovery. It, like everything Jackson produces, is a fiction.

But is it fair, really, to call it that? Because Jackson makes no claim that "Dymaxion Skeleton" is archaeology, it can not be dismissed as "junk science." It is contemporary art and, as such, is no less real than any relic released from the lower strata to be studied, interpreted and enshrined. And what can we surmise from Jackson's latter-day reliquary? To use Palmer's words, we're "not sure." "Dymaxion Skeleton" is cryptic and poetic. What are we to make of the connection between those root feet and the geodesic triangles? Or between Jackson's nod to Fuller, a half-baked scientist-engineer fascinated by Utopian machines, and this illuminated dead thing?

Admiring Jackson's skeletal creation, I think of the laudable efforts of David Wilson, the founder and curator of The Museum of Jurassic Technology in Los Angeles. Wilson's museum is an extension of the Wunderkammer, the sixteenth, seventeenth and eighteenth century rooms (or cabinets, as they were then called) devoted to displaying collections of natural specimens, artwork and other miscellany. Today we usually call collections of this sort curiosity cabinets (and, indeed, they more often occupy what we now think of as cabinets). The curator of "Wunderkammer: A Century of Curiosities," currently on exhibit at the Museum of Modern Art, points out that Wunderkammen are "precursors to museums." In the nineteenth century, these general interest collections were divided for display in separate art, natural history and technology museums. This breakup coincided with the shift from generalization to specialization, and although the latter approach allows for a more extensive body of knowledge, it is a less integrated one. An astrophysicist, for example, can tell you a great deal about astrophysics, but will likely contribute very little on the subject of crocodile anatomy. As John Walsh, former director of the Getty Museum, stresses, "in the earlier collections, you had the wonders of [the natural world] spread out there cheek-by-jowl with the wonders of man, both presented as aspects of the same thing, which is to say, the Wonder of God." Embracing the collage-remix instinct of the postmodern artist, Jackson shares much in common with his Wunderkammen forebears; he works to tap into the wonder current.

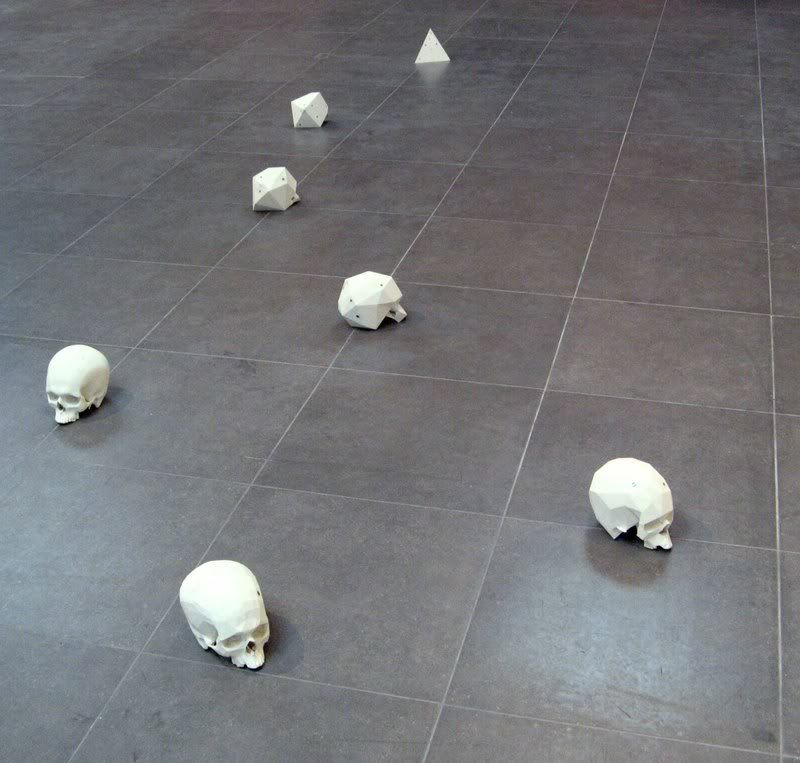

Matthew Day Jackson

"Against the Mythology of Linearity"

2008

Acrylic, abalone, mother-of-pearl

7 inches tall, dimension variable otherwise

Courtesy of Peter Blum Gallery, New York

"Against the Mythology of Linearity," a seven-stage transmutation, moves from a simple pyramid through five polyhedral forms before "becoming" a human skull. The increasing complexity of each stage seems to confirm linear progression rather than react against it, but Jackson has arrayed the forms on the gallery floor so that they constitute a question mark. The faceted shaping and abalone accents of these polyhedra allude to gem cutting and, with that craft in mind, I think of the Abrahamic Creation story, in which God makes Man and Woman on the sixth day, then puts down his chisel for a rest. By nodding to that story, is Jackson questioning the narrative that evolutionary biologists so vehemently defend? Perhaps, but with each additional facet, a polyhedron moves that much closer to a sphere, a "perfect" form that is emblematic of infinity. The skull, then, the seventh step, is not an end result. God can rest for a spell, but he should continue; his work is incomplete.

The economist and sociologist Max Weber said that the secularization of society and increasing specialization of methodological inquiry had led to a "disenchantment of the world." He was (and remains) correct. A world without magic is a meagre one. Jackson's best sculptures provide us with bread crumbs so that we might find our way back to wonder. They are redemptive works, and I eagerly anticipate more of them.

Photo credits: All Matthew Day Jackson images courtesy Peter Blum Gallery; Four Magisterium diagram, Christopher Reiger, 2008

7 comments:

Wowsers, that's a better blog post than our entire panel.

I'm sorry about raising lofty expectations. honestly, when we discussed the questions that would be asked pre-panel, it seemed like there would be more momentum, controversy, and velocity to the discussion. I'm not sure what happened there. I did try to gratuitously pick a fight with Jake just to liven things up, you know.

Did I even get to mention CP Snow? I can't remember. Grrr. I'm not sure I embrace Gould's NOMA model, but I guess it works better than anything else.

I love that my quotable contribution to your piece is the reiteration that I'm/we're/we should be "not sure". It reminds me of Obama in the first debate saying "John's right": accurate, but upon repetition, perhaps not quite the spin I intended? ;)

By the way, I made it to your show before closing - I was dazzled. Your work is amazing in person.

Bioephemera:

You don't owe me an apology, Jessica. After all, you tried to pick a fight. ;)

You didn't mention CP Snow, but your mention of him here, in the comments, led me to do some digging. So thanks. NOMA isn't perfect, by any means, but I find it a useful way to diagram (or describe) the relationship.

Finally, thanks for the kind words about the show. High praise, considering the source.

All the best.

I am glad someone is discussing these things, art, religion and science. They are intertwined. Where religion and science intersect, is art. I dont necessarily agre sith the schematic, but a good way to get the discussion going. It should be perhaps in three dimensions, and not necessarily gemometric, as all of these are very pliable, and what seems contradictory is really complementary, we just gotta ask better questions, which is what art and science are supposed to do. Good questions lead to more good questions, and that is quite enjoyable for those of us open to life, and not dogmatic. but constantly searching for more. thre is always more, or has been so far.

The Catholic church long ago accepted evolution, or at least dont question it. They see that science and religion are complementary, and the revealed truth of the material world is still of god. It is "fundamentalists" who have no idea what that is trapped in words for a distant age written by men of prehaps good heart, but limited knowledge.

Had along "discussion" of this over at Artnewsblog.com but I argue that philosphy has been replaced by both science and art, and religion is where the unknown is felt, and art attempts to visualize in word, sight, and song.

This is a very good blog, dont think I am being dismissive in the thread above. Just not a big Rothko fan, he is legit, jsut not on the level stated, or at least doesnt work for me. But then, we all have our own sensitivities to god and life. To what makes us human and our purpose, always appreciate an honest attempt. Thats all we can do.

ACDE

"...Jackson has arrayed the forms on the gallery floor so that they constitute a question mark."

It's actually laid out to depict the Little Dipper.

Anonymous:

Thanks for pointing that out! I hadn't made the connection. I'm not sure if you know the artist's intent, or if you just saw the Little Dipper in the arrangement, but I appreciate the insight.

Still, as "reading" art is a subjective enterprise, I'd hope that Jackson wouldn't mind my opting to go with the question mark interpretation. ;)

Your comments on Day Jackson are great. I enjoyed reading them.

I just saw his show at Houston's Contemporary Arts Museum. Blew me away. Very humbling experience.

The wall text hipped me to the configuration. I do think that is a more apt read, as well. Day Jackson's work certainly does present questions, as all good art will do. But great art also provides answers. Even if those answers are inevitably lies.

The fascination of man's "finding himself" in the natural world seems to be a theme for the artist as well.

Gspot:

Thank you; I'm glad that you enjoyed my response to Jackson's work.

If only more contemporary art provoked (or evoked) the sort of "humbling experience" you describe! Jackson is a very thoughtful artist, and I hope that his rigorous and soulful approach to art-making will begin to influence younger artists.

Post a Comment