Trenton Doyle Hancock

"Las Luces, Looses, and Losses"

2005

Mixed media on canvas

60 3/4 X 60 3/4 X 4 inches

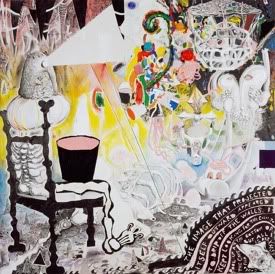

An inordinate amount of Trenton Doyle Hancock buzz was generated and disseminated this February and March. Hoping the coverage would die down and/or that my recollection of it would dim, I put off a visit to Hancock’s recent solo effort, "In The Blestian Room," at James Cohan Gallery, for as long as I could. Galleries aren't in the business of humoring persnickety calendar demands, however, and I found myself studying Hancock's handiwork with the hoopla still on my mind.(1)

Trenton Doyle Hancock

"In The Blesstian Room"

2005

Mixed media on canvas

90 x 108 x 6 inches

Clearly, I’m a biased viewer, but I found "In The Blestian Room" disappointing. My dissatisfaction is rooted in suspicion of motive, not, as one might assume, in aesthetics. That is to say, while some of Hancock's decisions - attaching studio detritus to the paintings, for example - seem self-conscious, fraught denotations of race, attitude, or spontaneous process, I was more disturbed by the sense that Hancock is dangerously close to becoming an art world personality. That is to say, his work seems calculated, more akin to Warhol than Darger or Dubuffet. Hancock turns his uncouthness into a commodity. As Donald Kuspit writes, "The artist outsider is well rewarded in our society - so long as he is an insider in art society."(2)

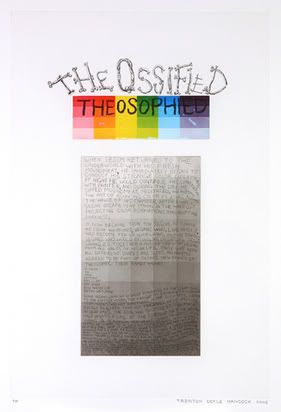

Trenton Doyle Hancock

“The Ossified Theosophied, (Title Page)”

2005

Color etching, Edition of 35

19 1/2 X 25 inches

Hancock's use of narrative scaffolding seems more like a marketing tactic than an essential ingredient in the artist's process. While it is not uncommon for contemporary artists to invent a cosmology on which to base a body of work - Matthew Ritchie is a notable example - most keep the details of their created worlds largely private. Hancock, by contrast, not only cooked up the Mounds saga, a picaresque epic with vaguely religious resonance, he also makes sure viewers know about it. “In The Blestian Room” includes a limited edition print (see above) that amounts to little more than a sloppy, hand-written chapter of the chronicle. Hancock is making up the story as he goes along – this, at least, is how it is presented to the viewer – giving it the appeal of a zany soap opera. (What is Sesom up to now? Come find out! What will he get into next? What crazy characters will he meet tomorrow? Will we witness a great war between the Mounds and the Vegans? You'll have to wait until the next installment/exhibition! Don’t miss it, ‘cuz the art world doesn’t do Tivo!)

Before I continue, it should be noted that I cheer for those making art away from established cultural centers; I enjoy comic books, graphic novels, and cartoons(3); I hold dear much fantasy and myth, from Kipling's "Just So Stories" and Aesop's Fables to The Lord of the Rings; I am fascinated by religious narrative and the clever weaving of historical "fact" with spiritual rendering in such tellings. Given this laundry list of likes, I expected to find a confederate in James Cohan Gallery. What I discovered instead was calculation.

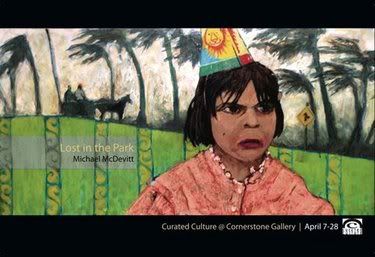

Lee Baxter Davis

"Family Tree"

2005

Ink, watercolor & collage

36 x 44 inches

What's more, Hancock’s still unrecognized debt to the artist who spawned him, Lee Baxter Davis, raises eyebrows. If I were not already an admirer of Davis, I very much doubt I would know of their relationship. The CUE Art Foundation recently exhibited about twenty of Davis’s drawings and paintings. Long overdue, the show was the artist’s first in New York. Early in the associated press release, the writer draws attention to Davis' influential role.

“A regional icon, Davis’ thirty-years of teaching printmaking and drawing at East Texas State University (now called Texas A & M, Commerce) has influenced the careers of some of his very prized students including exhibition curator, Gary Panter, along with Whitney Biennial artists Trenton Doyle Hancock, Robyn O’Neil, and Christian Schumann, among others.”An Internet search for “Lee Baxter Davis” turns up little, whereas “Trenton Doyle Hancock” nets many relevant articles and websites. In pieces about Hancock, the names William Blake, Hieronymus Bosch, Philip Guston, Max Ernst, and Gary Panter are repeatedly cited as influences, but Davis is nowhere credited. This is a curious oversight, the result of Davis' being a relative unknown in the New York art world. Closer to home - his home - he looms large.

"In the 1970s, The Lizard Cult was a vaguely derogatory term applied to East Texas State University (as it was known then)'s Art Professor Lee Baxter Davis and many of his most talented students. It was called that because so much of their work closely approximated his - rife with comic sensibility, lush textures and lurid details....Once viewed with condescension, The Lizard Cult has not only grown up, many of Davis' students have prospered and become regionally and nationally prominent." (J R Compton, "Lee Baxter Davis and The Lizard Cult Grows Up," Dallas Arts Review)With the exception of Gary Panter, Davis' celebrated proteges are all much younger (by thirty or more years, typically) and, therefore, more attractive (for the moment) to the youth-obsessed art market. Furthermore, whereas Davis is a retired art professor now working as an assistant pastor of St. William the Confessor Catholic Church in Greenville, Texas, his former students manage to bridge the divide between "living and working" in Texas and, well, living in Texas. In other words, though Hancock and O'Neil still live in the state (Paris and Houston, respectively), they have attached themselves to the larger art world in a way that Davis has not. Why, one wonders, have so many of Davis' students achieved art world success while he remains a regional icon? In part, the answer lies with the man himself, with a desire to remain unrecognized, but I can't shake the sense that a more perverse process is also at work.

Lee Baxter Davis

"Big Bear"

2005

Pen, ink, watercolor & collage

21" x 29 inches

In his recent indictment of postmodern art, The End of Art, Kuspit describes two artist archetypes. The first is a "reclusive alchemist struggling to purify the dross of everyday reality," and the second, an "entertainer representing a mass audience's everyday wishes." Although Kuspit argues that the monkish model is exclusively modern and, today, extinct, this is not the case; both are alive and well. As a general rule, however, it is the second type, those interested in "having an audience that will make them popular, giving them the celebrity and charisma they believe they are entitled to as artists," that finds success in the art world.

Lee Baxter Davis is the very picture of Kuspit's reclusive alchemist. Not only are his paintings alchemical, but his lifestyle and approach to art-making fit the bill, too.

"Like a hermit practicing his art in millennia past, Davis is isolated. He has chosen to separate himself from society, locating his studio, home and family life far from the hustle and bustle of Dallas, Houston, San Antonio, or Austin. Davis finds peace and purity of existence in the quietude of a rural existence. Instead of reaping and sowing the land for its hearty edibles, he reaps and sows the earth for intellectual nourishment. It is a type of sustenance that could only come from the coupling of separation and deliberation - from self-willed banishment to the silent wilds of a life found deep in the nowhere lands of Texas." (Charissa N. Terranova, "Alchemist of Imagination," ARTL!ES, Issue 43)Furthermore, Davis is as invested in (or consumed by) his contemplation of philosophy, religion, and pop culture as he is the local environment.

"Growing up in the small towns of Texas, Davis' boyish pursuits included immersing himself within the complex sagas told by great Southern writers, the harrowing poems of Edgar Allen Poe, and a dizzying array of post WWII popular comic books and newspaper strips such as BlackHawk, Pogo Possum, and Mad Magazine. Largely raised by his Methodist minister grandfather, and having read the bible since childhood, Davis has long harbored a deep-rooted fascination with the more mysterious elements of faith...Believing laughter and prayer to be close to the same thing, he creates illusions whose idiosyncrasies harbor nervous fits of laughter as buffers against existential angst."(Gary Panter, "Lee Baxter Davis," CUE Art Foundation press release)

Davis' layered pastiche is, for him, a metaphysical search, one that ties vulgar realities to marvelous visions, the profane to the sacred. Viewers - western viewers, in particular - will recognize many of the embedded symbols, but they must interpret the work subjectively, nurturing their own hybrid narrative. Thus, something approaching the intrinsic alchemy of the making - Davis' journey - is experienced by the viewer. To an extent this is true of all visual art, but Davis' symbolic content elevates the exchange.

Hancock's Mounds fiction, on the other hand, is altogether different. Viewers must learn about the Mounds before the narrative becomes meaningful. We are given a choice: disregard the mythology and treat the work as illustrative reverie, or become an initiate of Hancock, learning the magic words, the symbols, and the gestures. In essence, Hancock offers viewers a cult of personality. Davis allows us a subjective experience by drawing on shared myth; Hancock gives us an opportunity to participate in his manufactured, flimsy one.

Yet the son has surpassed the father, at least in terms of renown. Hancock is more savvy than Davis. Whether by virtue of his nature or the waving of an agent's wand, he presents us with the "high art" version of an "outsider"/low-brow aesthetic. His awareness of the supposed division between these two orbits is clear. For many, this makes the work more easy to digest, but also more intelligent and contemporary. For others, myself included, that awareness results in self-conscious painting, work that excels at distraction and affirmation, but fails to address universal experience. Many critics (many friends) disagree, arguing that Hancock melds rich narrative, magic, superstition, faith, and popular culture to produce an original experience, a distinct and contemporary remix. But the father's artwork suggests that same union is less an artistic assertion of individuality than a way of life, an approach allowing us to cope with and consider deeply disturbing axioms.

Lee Baxter Davis

"Sideshow"

2005

Pen, ink & collage

28" x 20 inches

(1) Museum exhibitions have a longer lifespan, allowing the details of the 2006 Whitney Biennial coverage, for example, to fade before I finally visit (in late May).

(2) Donald Kuspit, The End of Art, Cambridge University Press, 2004

(3) In fact, I feel Hancock is better served when he sticks to comics - there were some strong pages on display in the rear gallery - and the like. His book, "Me A Mound," is a far more interesting artifact that his paintings or prints, though it, too, suffers for a certain amount of ostentation.

Photo credits: All images ripped from James Cohan Gallery and CUE Art Foundation websites