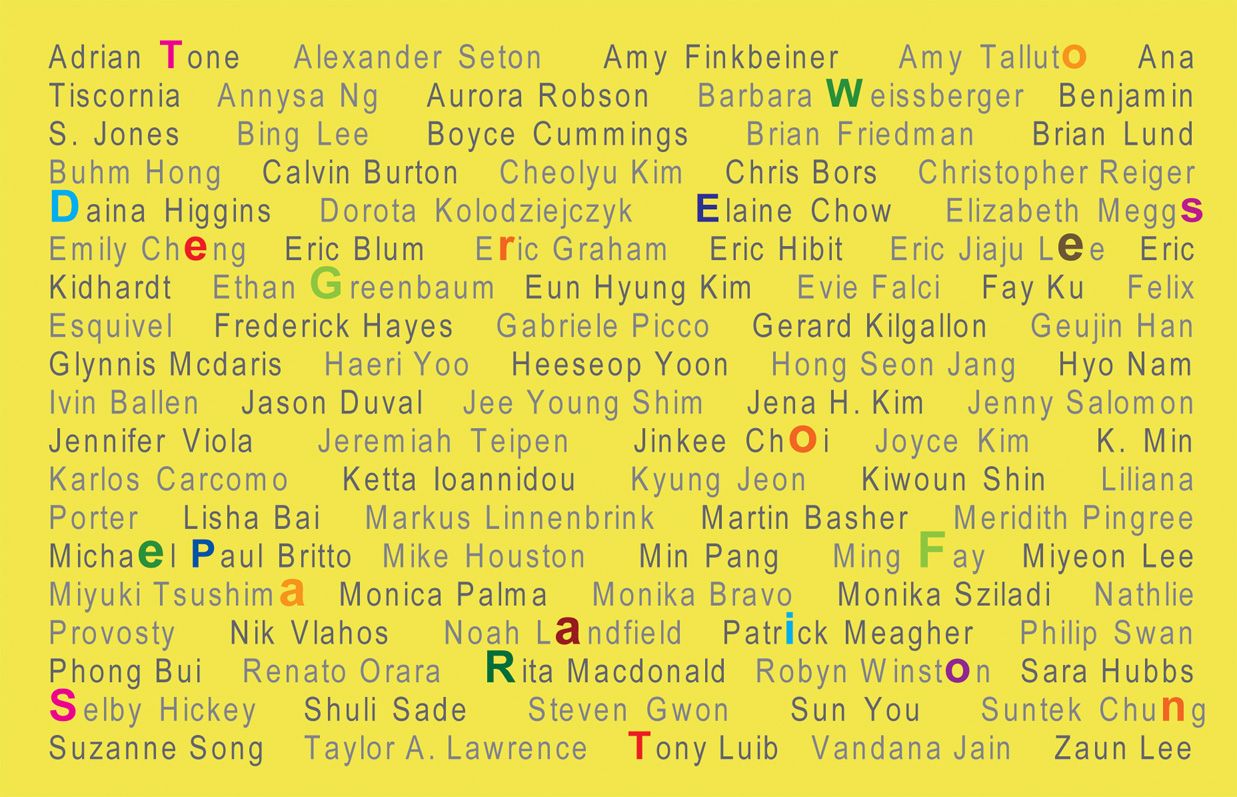

Christopher Saunders

Christopher Saunders

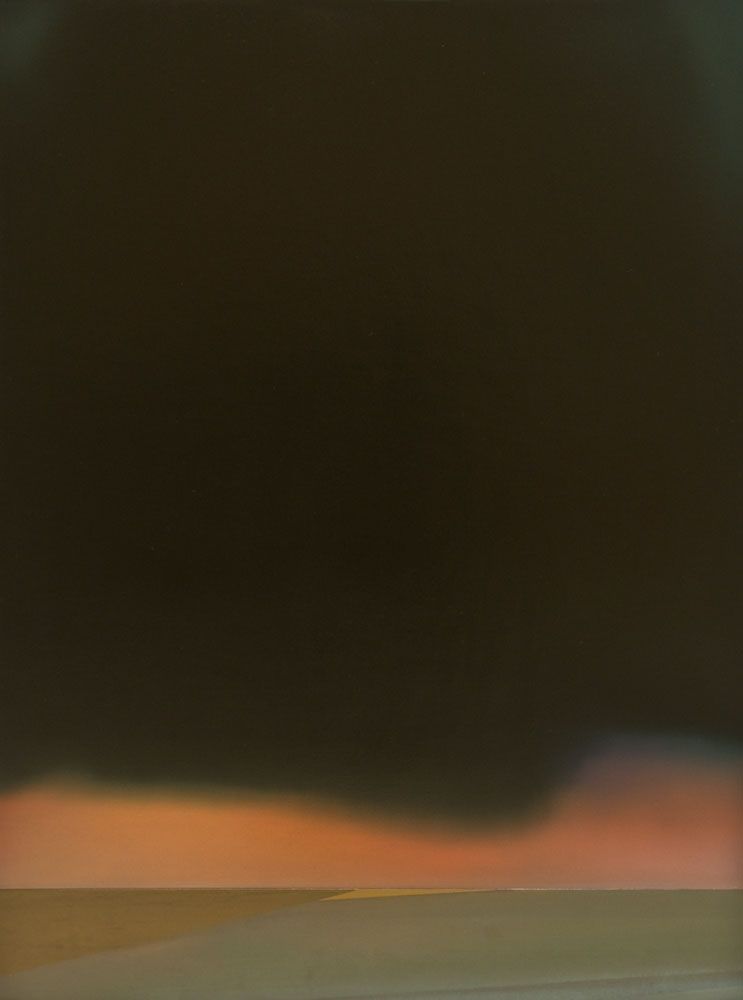

"Whitenoise no.8"

2009

Oil on linen

24 x 18 inchesA regular passenger on

New York City's

subway system, I'm grateful for the

Metropolitan Transit Authority's "

Poetry in Motion" and "

Train of Thought" programs, efforts that repurpose subway advertising space as a showcase for poetry or significant quotations. This week, I noticed the German philosopher

Arthur Schopenhauer's quotation, "Every man takes the limits of his own field of vision for the limits of the world." I appreciate the substance of Schopenhauer's cynical observation, but I would amend his statement. Certainly, too many men

do take the limits of their field of vision for the limits of the world, but the truly reverent man does not mistake the two for the same. As the critic, author, poet, and essayist

Wendell Berry describes it, "to feel reverence, to be reverent, is exactly to surrender the 'precious self.'" In surrendering the self, we accept our insignificance, we recognize the infinitesimal reach of our individual vision. And yet, counter intuitively, this same surrender of self also opens our field of vision to the infinite variety and scope of being; through negation, liberation.

Schopenhauer and Berry again came to mind as I contemplated

Christopher Saunders' "Whitenoise" paintings in

LaViolaBank Gallery's group exhibition "

Outside In."

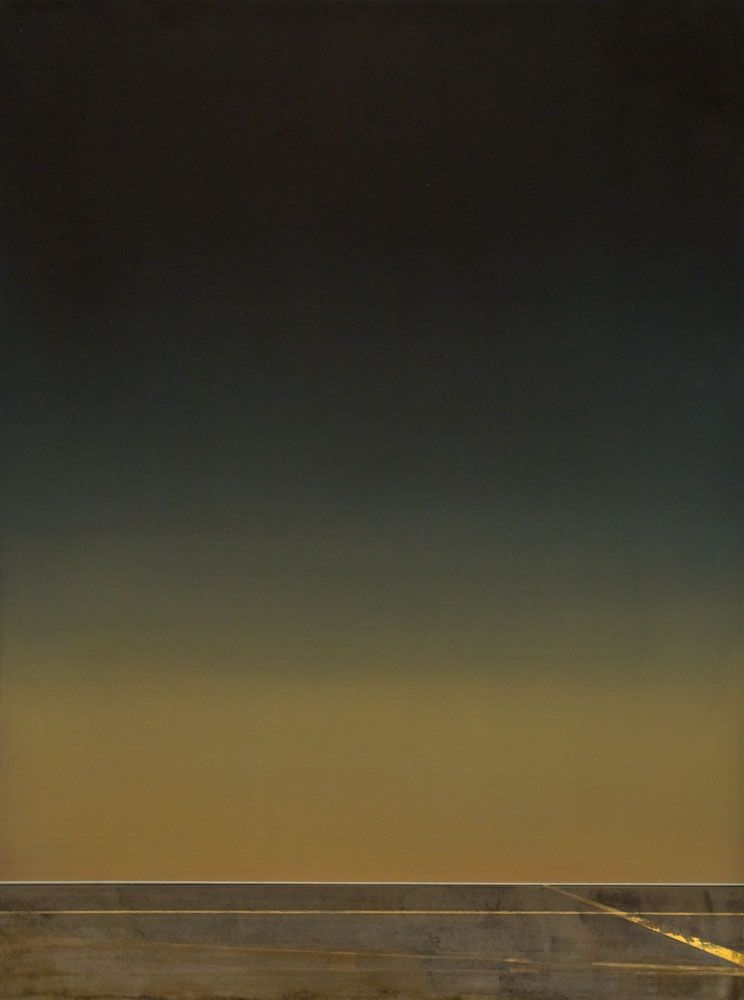

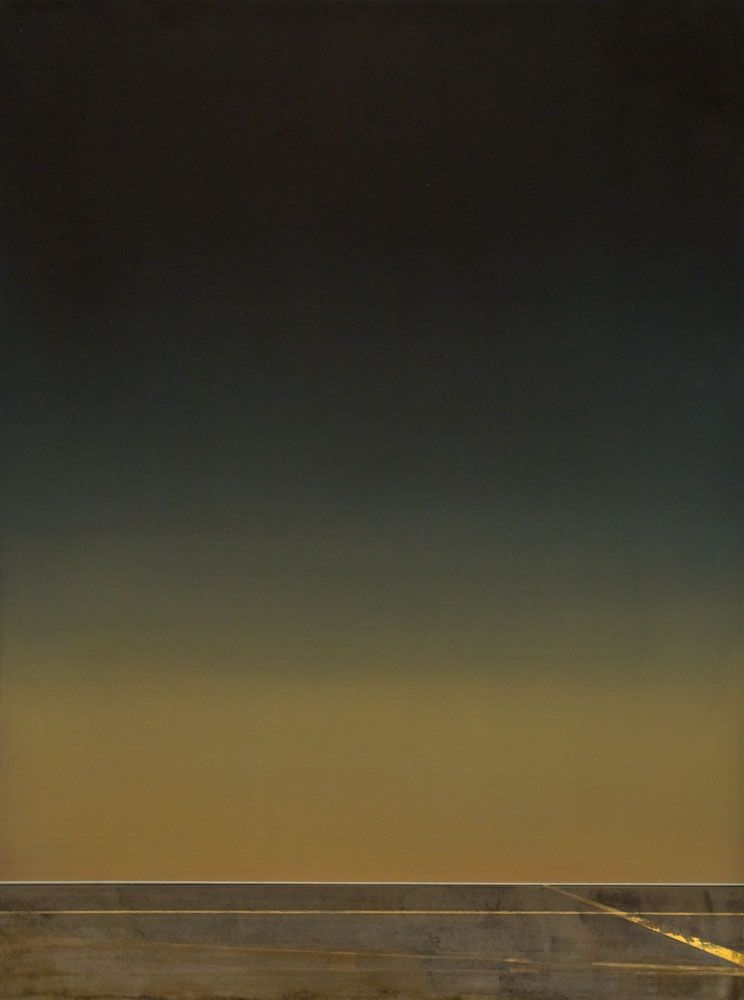

(1) Dark and cloudy skies dominate Saunders' vistas, and the horizon in these flatland pictures draws a conspicuous boundary between sky and earth. In "Whitenoise Suite no.4," an ominous storm front moves over a lonely stretch of highway; a pitch veil chases away a sunset in "Whitenoise Suite no.8"; and in "Whitenoise Suite no.9," a brooding twilight settles above a tarmac. There are echoes of

Mark Rothko's

luminous melancholy in Saunders' work, but his atmospheric paintings seem most akin to the

Romantic landscapes of the 17th, 18th, and early 19th centuries.

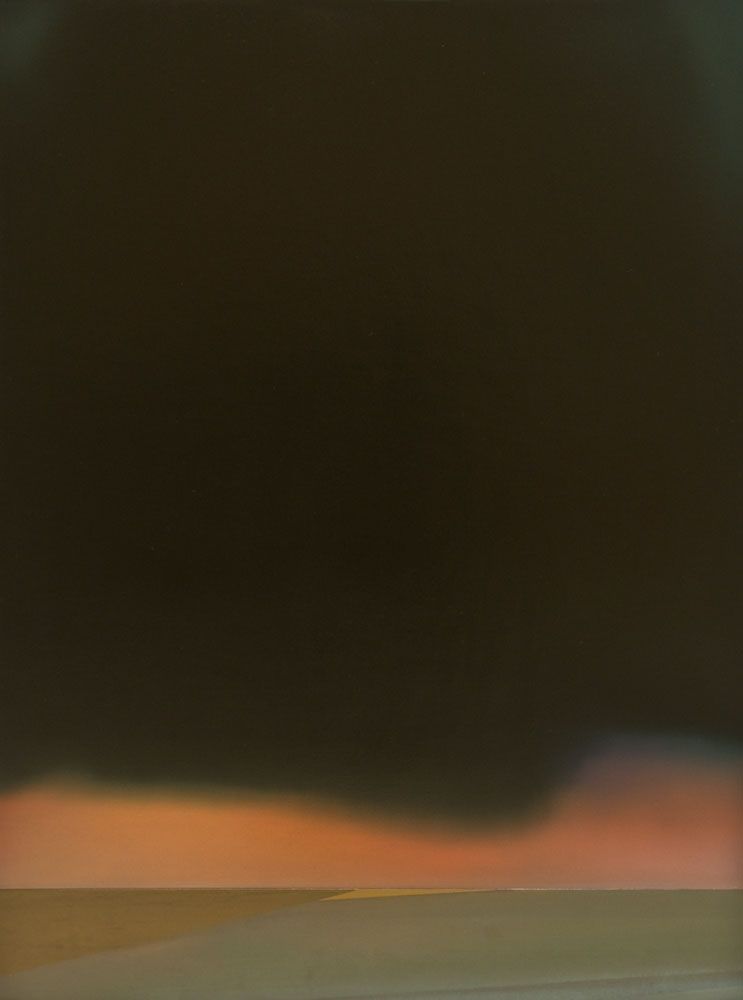

Christopher Saunders

Christopher Saunders

"Whitenoise no.9"

2009

Oil on linen

24 x 18 inchesCaspar David Friedrich is perhaps the most celebrated painter of

the Sublime, and his "

Wanderer above the Sea of Mist" (1818) is among the best known examples. The work pictures a well-dressed, solitary gentleman, his back to the viewer, positioned confidently atop a rocky crag as he surveys a vast, mountainous landscape that is mostly obscured by fog. Concurrent with Friedrich's work on the famous painting, his friend

Carl Gustav Carus described Sublime experience in a passage that could well have been written in response to "Wanderer."

"Stand then upon the summit of the mountain, and gaze over the long rows of hills. Observe the passage of streams and all the magnificence that opens up before your eyes; and what feeling grips you? It is a silent devotion within you. You lose yourself in the boundless spaces, your whole being experiences a silent cleansing and clarification, your I vanishes, you are nothing. God is everything."

Carus' experience of the Sublime is, like Berry's reverence, a reduction or erasure of the self-conscious individual and a simultaneous opening of the individual to the wilderness within. His dramatic description brings us back to the moody Schopenhauer, who prescribed the Sublime as a remedy to his every man limits. In his volume

The World As Will and Representation (1818), Schopenhauer elucidated

a scale of aesthetic experience. At one end of this spectrum, he described the "Feeling of Beauty" as "Light...reflected off a flower. (Pleasure from a mere perception of an object that cannot hurt [the] observer.)" At the other end of the spectrum, the philosopher positioned the "Full Feeling of Sublime" and the "Fullest Feeling of Sublime." These categories are described, respectively, as "Overpowering turbulent Nature. (Pleasure from beholding very violent, destructive objects.)," and "Immensity of Universe's extent or duration. (Pleasure from knowledge of observer's nothingness and oneness with Nature.)" At the amplitude of "Fullest Feeling," then, Schopenhauer's aesthetic philosophy is reconciled with that of Carus and Berry.

Most modern humans (especially modern humans in

the First World) are insulated from inclement weather. We fret over a rained-out ball game or beach party, but we rarely tremble before dark cloud heads; our appreciation of the elements is principally one of admiration, an aesthetic experience that resides near the middle of Schopenhauer's scale. But Saunders' landscapes provide viewers with a vantage point that repairs the reverent awe that we once felt before the expansive firmament. He does not include the rugged, mountainous imagery familiar to most artistic depictions of the Sublime. Instead he portrays clouds pushing over a featureless land, the violent potential of atmospheric flux readily observable at a distance. The clouds, vast, magnificent, menacing, dominate Saunders' compositions; they are the rough mountains of our inner wilderness. Despite the "Whitenoise" paintings' relatively small size, their effect is formidable. Before the strongest in the series, I stood quiet.

Christopher Saunders

Christopher Saunders

"Whitenoise no.4"

2008

Oil on linen

24 x 18 inches(1) Although Saunder's oil paintings preoccupied my imagination, related ideas are addressed by the work of other artists included in the "Outside In" exhibition. I also admired

Diane Carr's fluid and evocative landscape paintings,

Leighton Pierce's hypnotic video of a woman underwater, and

Mira O'Brien's photographic floor installation.

Imaged credits: all Christopher Saunders' works, courtesy of

the artist