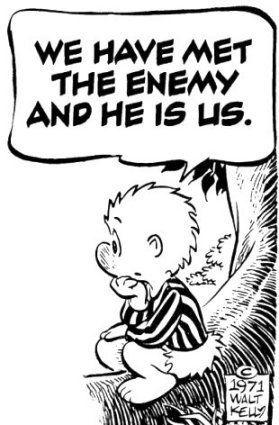

Much later, sometime after our cellphones lost an hour, I stood outside a party on Bond Street, quite drunk, talking with a good friend about nothing. I mentioned something about painting and he placed a hand on my shoulder, as much to dramatize what he was about to say as to steady himself. "You know what you do is bullshit, right? I mean, it's all irrelevant. No one cares about painting or art anymore. You recognize this, right?" I do, of course I do. The Art World has withdrawn from society in the same way that academia, the theater or opera has. These are now esoteric arenas, marginalized - even pilloried - in the eyes of "the people." My friend continued, "I mean, it's not just painting or fine art. The same is true of classical music. These are mediums that screwed themselves. It's not your fault the Art World made itself irrelevant but, because of that, you're making irrelevant work." Fortunately, I was too drunk to sit on his dose of downer realism and I returned to the party no worse for the wear, if three sheets to the wind.

The next morning, I woke with a headache, dehydrated calf muscles and the memory of my friend's words. I had so easily brushed them aside when drunk, but I was now forced to retreat, to delay the confrontation, by rolling over and welcoming more sleep. I so wanted to wake up, to go into the studio and have a productive Sunday, but the knowledge that "no one cares" was too present, a cartoon thunderhead hanging above my pillows in an otherwise bright, sunny room. When I finally did rise, reluctantly, I wandered into the kitchen, fed my cat, put on some water for tea and ate a banana while I stared out the window and played with my belly hair. Banana finished, water not yet rolling, I decided I had better head to the toilet for some overdue release. On the way, I paused to lean against the frame of the studio door and survey the paintings in progress. Elation! Thirty seconds of looking was all it took; I was renewed. The thunderhead evaporated in the warm light and I made my way to the toilet free of worry about the irrelevance of contemporary art. After all, art is not at all irrelevant to me.

+++++++++++++

Nancy Margolis: Kim Simonsson's ceramic sculptures are really cool looking. I love his - Kim is a him - sculpture of a doe-eyed manga troublemaker allowing a string of spit to hang down from her pursed lips. I'm also attracted to the two fawn pairings in the rear of the gallery. But so what? These are well executed, fun sculptures, but they leave me wanting a more substantial experience. Simonsson's artist statement suggests that he is interested in exploring contemporary societal ills by producing work that "call[s] forth questions" while "blur[ring]the distinction between traditional art and popular culture." Well, don't we all aim to produce such work? Personally, I think he just likes making really cool looking sculptures.

+++++

Metro Pictures: I want to like Jim Shaw's work, but I rarely do; his latest New York solo effort is no exception. One of my friends liked the green-tinted resin sculpture at the back of the main gallery space, but it reminds me too much of my own art school resin fetish. Shaw melted and glued toys and colorful plastics together to produce a human-slug hybrid that calls to mind the Toxic Avenger or the Trash Heap from Fraggle Rock. Like the rest of this show, which features painting, drawing, sculpture and one marriage of painting and installation, this piece can't be called bad, but it is boring.

+++++

Luhring Augustine: Ever since I saw the original Star Wars, I have been interested in designing my own chess set. Whether populated by holographic alien beasts (as in George Lucas's imagining), wizards, animal species or street gangs, I've always gotten a kick out of "alternative" boards and players. Unfortunately, my half-hearted attempts - usually Sculpy creations - never turned out as I desired; maybe one day, somewhere over the rainbow, I'll have enough money at my disposal to design a set I really love. I was pleasantly surprised, then, by "The Art of Chess," a group show at Luhring Augustine featuring ten artist designed chess sets. Alas, we are all individuals and most of these sets belong to another's sensibility. For example, Rachel Whiteread casts her collected dollhouse furniture and uses the sofas, chairs, and nightstands as player stand-ins. The board is comprised of squared carpet samples. I thought it colorful, but subjectively uninteresting and, more importantly, far from pragmatic. It would be difficult to distinguish king from rook or queen from pawn when each piece is distinct, both in terms of color and design. To make things more confusing, there are no repeated forms; rather than having one design for bishop or knight - a recliner, say - all four knights are different items of furniture. I didn't get the sense that Whiteread intended the set to be used for a real game.

There were two chess sets, however, that I though tremendous. Maurizio Cattelan created a "Good & Evil" set (pictured above), featuring delicately crafted players from diverse backgrounds. Hitler stands at attention on the evil side, while Martin Luther King, Jr. and Jesus stare back at him, unintimidated. Again, this set suffers for being a little difficult to play with - without a cheat sheet, it is hard to remember which pieces are what - but it is sexy enough to have me salivating. Good looking and pragmatic, the Chapman brothers present us with a slightly disturbing version of the classic chess set. Each side is coordinated by skin tone - one side Caucasian, the other black - and all players are penis-nosed pubescent girls, some riding on the backs of their friends. Here at last is a set that repeats forms for the respective pieces, making this the most playable set in the exhibition.

+++++

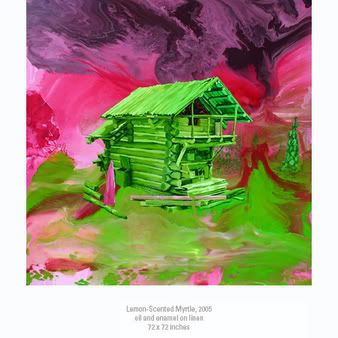

Goff + Rosenthal: Reproduced in an advertisement for his exhibition, Stephen Bush's paintings caught my eye. In person, however, I am ambivalent. The swirls of abstract color seem arbitrary and the representational elements - cabins, bridges or other constructed forms - don't speak to human isolation or individualism in the way I thought they might when flipping through the pages of Art Forum. That said, I get the feeling that Bush is heading toward a more thoughtful body of work.

+++++

David Zwirner: The biggest dud of the day was the Luc Tuymans show at Zwirner. According to the press release, these new paintings "[put] forth the image of a fragile America and the crumbling state of current affairs," but one of my friends described the pale paintings more colorfully: "This is too bland even to be hotel art." I can't help but agree.

+++++

Charles Cowles: I have been enamored of Edward Burtynsky's large-scale photographs for years now. His subject matter - sprawling industry, scarred natural landscapes, urban development - has become standard issue Art World fare, particularly among the younger photographers finding favor in the press, but Burtynsky turned his viewfinder on these subjects years ago and he produces more powerful, meditative images than the majority of his imitators. This selection of photographs from China showcases his eye for color and composition and his instinct for isolating emotional heft in landscape.

+++++

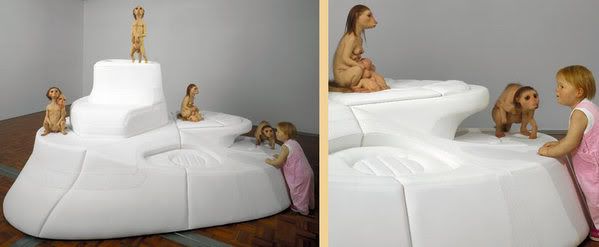

Robert Miller: I've been eagerly awaiting Patricia Piccinini's current solo show for several months and, though it doesn't disappoint, it is a mixed bag. The included photographs and video are very weak, but most of the sculptures and several of the drawings are as satisfying as they are grotesque. Continuing her investigation of genetic anomalies and fringe hybrid experiments, Piccinini presents viewers with a new cast of characters. My favorites are featured near the front of the gallery; part mole rat, part flying squirrel, part gopher, these intimidating little beasties apparently like to attack human faces. Close inspection of the back pouches on her "Surrogate" creature, in the rear gallery, will revolt many gallery visitors. Piccinini's attention to detail is admirable, on par with that of Ron Mueck, and I like her subject matter a lot. She does need to be careful, however, to avoid transitioning into a prop artist. The series of photographs turns some of her creations into just that - they harass construction workers or watch NASCAR on a fence - and, frankly, they look awful. Piccinini is no Hollywood special effects whiz and attempting such a series calls to mind Charlie White, an artist who should have gone into B-movie production where his talents would have been put to better, more complete and gratifying, use. (The image of Piccinini's work seen above is not current. The Robert Miller website is awful.)