Sculptor and performance artist Dominique Mazeaud recently proposed on her blog a "second round of 'Les Magiciens de la Terre,' an exhibition held at the Centre Pompidou in Paris in 1989, that asked one hundred artists to define art along with showing their work." Mazeaud, however, throws a curve ball: "I would simply change the question and ask artists to offer a definition of 'what is the spiritual in art.'"

Defining the spiritual in art is no mean task. The curators of Mazeaud's proposed show would likely receive as many different responses to the question as there were artists participating. Contemporary spirituality, after all, is understood to be an individual quality or experience. But a diverse field of responses doesn't make the question any less interesting, and I agree with Mazeaud that such an exhibition would be exciting and insightful, especially in light of recently reinvigorated conversations about the role of art, artists, and the art market.

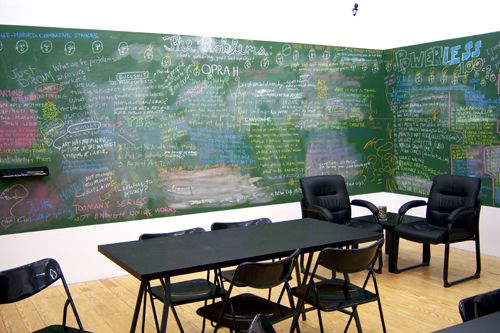

Presently, at the Winkleman Gallery, artists Jennifer Dalton and William Powhida offer a platform for this conversation. They've created a temporary "think tank" for "guest artists, critics, academics, dealers, collectors, and anyone else who would like to participate to examine the way art is made and seen in our culture and to identify and propose alternatives and/or reforms to the current market system." I readily admit that I'm more interested in talking philosophy and "ultimate meaning" than I am in discussing practical approaches to the contemporary art market, and I believe that my charitable sales model implicitly announces my ambivalence about (and proposes a viable alternative to) our day's dominant system. That said, only naive artists truly believe that contemporary art can exist completely disconnected from the market (while still finding an audience).

Unfortunately, I arrived late to James Leonard's performance piece on Thursday night (thanks to the snowfall some news sensationalists dubbed "the snowicane"), and I had a conflict that kept me from attending the presentation by Barry Hoggard and James Wagner last night, but I hope to make at least a few more of the sessions that Dalton and Powhida have lined up. You can view the calendar at the exhibition/think tank blog, Hashtagclass."

Image credit: ripped from the Winkleman Gallery website