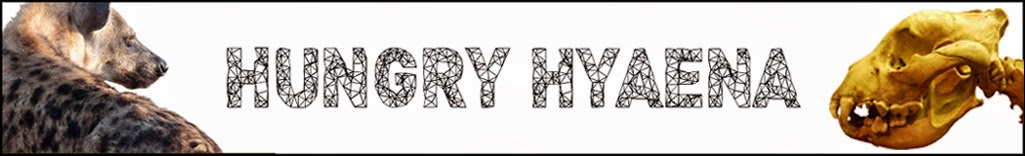

Alton L. Larsen

Alton L. Larsen

"Lewis and Clark"

Oil on canvasI'm thrilled to announce that I've been accepted to the

Kimmel Harding Nelson Center Artist Residency in

Nebraska City,

Nebraska. During the two week, September term, I plan to explore Nebraska City and the surrounding land with an eye toward the region's natural history, focusing particularly on the

Lewis and Clark Expedition and the legacy of 19th century westward expansion. Most of my time will be spent outdoors, biking and walking around the town's trails, parks and historical sites. In the evenings, I'll use the provided studio space to conduct research, work on painting studies and drawings, and write essays relevant to the residency. (The essays will be posted here.)

I'm very much looking forward to my time in Nebraska, just as I'm eagerly anticipating an upcoming week of

birding,

herping and bumming about in

Florida with two friends. My usually vigorous city disposition has withered in recent weeks, and I long for time in the woods, marshes or mountains. Saturday afternoon, taking a break from helping my girlfriend move some of her belongings, I sat on a stoop, attuned my breathing and appreciated the pompous sidewalk display of a

pigeon courtier. A few minutes later, I trembled with a renewed sense of well-being as a curiously bronze

House sparrow contemplated me (contemplating it).

These simple encounters with urban wildlife are a joy. I'm grateful for them. This week, however, the sparrows, pigeons, squirrels, starlings and gulls have only whet my appetite for time away from urban and suburban environs.

My sense of urban exile was exacerbated this afternoon, when I listened to a podcast of "

The Thomas Jefferson Hour." Historian and Jefferson impersonator

Clay Jenkinson described contemporary man's changing relationship to Nature.

"I've been flying over North Dakota lately and North Dakota is just one tiny little place at the top of the continent, but [...] between the Mississippi River and the west coast there is still a gigantic amount of unspoiled land. [...] It's still a pretty light industrial footprint. [...] Of course, you can see human presence there: power lines, contrails from airplanes, mines, vanity houses, ridgeline developments. [...] But [...] there is still a large amount of America [...] in which there are literally hundreds of national and state parks and national monuments and national forests and wildlife refuges which are permanently protected against gross economic, extractive development. [...] We have an enormous amount of Nature which has been designated, officially, by the will of the American people to be off-limits to certain types of activities. [...] I feel that that moment - which begins really with Yellowstone in 1872, but got it's big push from Theodore Roosevelt - that moment kind of culminated around 1975 or 1980 and, since then, there's been a kind of pulling back of national commitment to these issues.

And now there's a generation of people who are growing up with no particular interest in this. They're detached from it. They're a little bored with Nature. They don't want to go camping; they don't even want to go hiking. They only want to be on their iPod and their [...] computer, the Internet, and Facebook, and Twitter. [...] That's their mediation. That's how they see the world, [...] and they're bored with sitting around that campfire. [...] So as this happens, as we move into [...] this incredibly electronically mediated, post-literate, post-natural world, it's frightening to people that still believe that that was the glory of America.

I'm one of them! I believe that the national park system is America's greatest contribution to the world, or at least it's one of the top handful of contributions we've made. [...] The point I'm trying to make is, if the population [of the United States] is 330 million, there are about 300 million who don't care one iota for this, and they're very, very happy to eat their chicken in a hermetically sealed container and not know the first thing about where their lights come from and not care how the natural world works."

I wish that I could claim urbane sophistication, thereby dismissing Jenkinson's melancholy perspective as misguided nostalgia. But I can not. Even though

I proclaim a long view optimism (and therefore acknowledge the absurdity of wishing for what once was), I feel that the ignorance of most First World citizens of the natural world is unpardonable. It is an insult not only to my naturalist's sensibility, but also to the philosophical, biological and cultural ground on which thoughtful humans stand (and build).

Despite my fondness for cosmopolitan politics and culture, in at least this respect, I sympathize with

Thomas Jefferson's belief that cities are "pestilential to the morals, the health and the liberties of man." By further insulating us from our animal antecedence and the brute realities of Nature, cities slowly erode

our practical call to stewardship.

Shortly after Jenkinson's podcast ended, a familiar voice interrupted my painting. I wasn't sure that I'd heard rightly over my headphones, so I peered out of the studio window for confirmation. Sure enough, a

mourning dove was perched on the fire escape above me. Periodically, it uttered a nesting call, an abridged version of

the plaintive call that many Americans are familiar with (whether or not they can identify the species responsible). I could see no mate or nest, but I'm delighted to learn of this new neighbor.

Unfortunately, this week's creeping cynicism makes me doubt if my

human neighbors notice the birds. I hope that this brooding will soon pass. Pessimism does no one good.

Photo credit: image ripped from

Blair Congregational Church United Church of Christ website