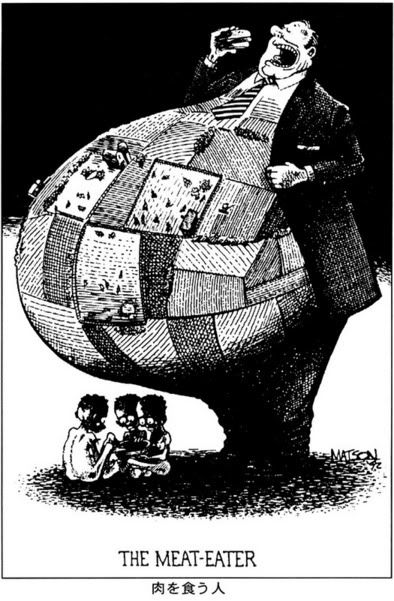

“The show suggests that artists are connected to events in the outside world but have little sense of what to do about them, other than to create artworks that incorporate their frustration, rage, apprehension or sense of the absurdity of contemporary life.”

- Eleanor Heartney, Art in America, review of “Greater New York, 2005”

Who would condemn a child for having an active imagination? In contemporary western culture, most parents celebrate the fantasy lives of their children (or at least tolerate them), no matter how consuming they may be. This is for the good; a rich, imagined world often leads to greater curiosity about the world we inhabit. There are, however, some legitimate concerns for those children who appear to withdraw into fantasy too much, those who exhibit a tendency for escapism. These kids can be spotted at an early age. I should know.

As an only child who grew up in a rural farming village, my interaction with other children was limited to the school day and the rare overnight visit to a friend's house. My father, an unabashed workaholic, kept me occupied with field chores and

wildlife conservation projects on most weekends. Our house had no television, the upshot of which was that I won most every reading competition until I reached 6th grade (the year -- holy of holies! -- a television arrived). I turned to books and invention for entertainment. The fields and forests were places of extraordinary mystique, vast plains teeming with bison and Indians or thick, dangerous woods with thieves and bizarre creatures lurking behind every tree. The pond shoreline represented a potential aquatic

dinosaur attack, forcing me to walk just so to avoid detection.

But the fun didn’t stop at nightfall. No, if anything, the level of “make-believe” only increased once I was forced indoors. I would stage plays in my bedroom, becoming the voice of a stuffed animal perched on the windowsill and that of the angry, invisible dinosaur, the evil step-mother, the diminutive

Lego man on the shelf, and so on and so on. (For some reason, many of these epic plays resulted in a raccoon puppet ripping open my throat. Of course, I was then re-animated as a rabid monster that would stalk the room’s perimeter, hunting imagined company.)

Despite my protests, it wasn’t at all inappropriate then that some kids called me

Christopher Robin. I was tremendously uncomfortable in most social situations and I really didn’t trust any of my peers. During recess, I was the kid who retreated to a corner of the playground and talked to myself or played with blades of grass, imagining I don’t know what. It was also not surprising that cartoons, comic books, and drawing soon dominated my life outside of chores and schoolwork. I was every elementary school teachers’ dream, the quiet kid who scores well and gets placed in all the advanced classes, but shows no sign of ego or contempt. In fact, I was just oblivious to most of what was happening around me. I had no idea what interested most of my classmates. I didn’t listen to popular music until the sixth grade and most of my pop culture understanding was garnered from the pages of

MAD Magazine. I knew what a phenomenon

Michael Jackson was, but I'd never heard his music.

None of this mattered to me, however. I remained an essentially happy kid. I just shut out everything except my drawing, reading, and my fantasies. I'd learned how to tune out without ever having tuned in. Fortunately, the years have been kind to me and, rather than go the way of

the Unabomber, I’ve become a reasonably well-adjusted member of society, if still something of a loner who likes to draw, read, and write.

It is with increasing urgency, though, that I view so much art produced by my contemporaries, artists in their twenties and thirties. An uncredited

New Yorker writer describes this work as, “gloomy, craft-spun, fairy-tale escapism endemic among young

East Coast artists.” A visit to

Greater New York, 2005, a survey of artists living or working in

New York City at

P.S.1, will illustrate just how prevalent this mode has become. Fully 40% of the work on display fits the bill, and while the majority of these are paintings or drawings, a number of videos and installations belong to the same impetus. We are a generation uncertain and intimidated. Rather than engage and participate, we have opted to wear the escapist smile, retreating into the worlds of

Alice and the

Little Prince. Is it enough to express ourselves in this way? Do these cryptic fairy-tales or self-abusive efforts communicate anything more than immediate frustration? After all, it was largely my social incompetence which drove me to chase monsters around dark living rooms. How much different is this display?

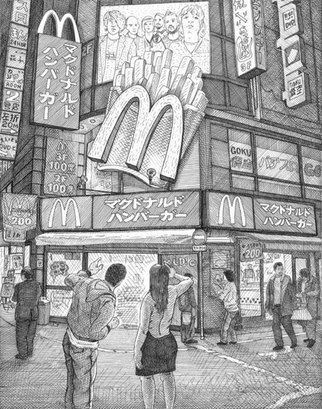

These currents aren't isolated to the eastern seaboard of the United States, though. Admittedly, the majority of young

West Coast artists still seem to be preoccupied with abstraction and pretty pictures, but the dystopian fairy-tales are being createed by artists not just from across the

United States, but also via imports from

Japan,

Europe,

Iceland, and elsewhere.

Peter Schjeldahl recently wrote of

Takashi Murakami’s curatorial effort, “

Little Boy: The Arts of Japan’s Exploding Subculture,”

“[The included work] suggests a certain pathology: rapturous defeatism, perhaps, that justifies youths who don’t grow up.”

It seems as though an entire generation -- global, not just Japanese -- has been forced into perpetual adolescence by the atom bomb that is our modern condition?

At the turn of the century, very few people knew anything about

Henry Darger, the reclusive painter/janitor from

Chicago who spent the bulk of his solitary life working on a series of collage-like, narrative drawings depicting the history of the Vivian Girls. The currents of the art world, circa the late 1990s, were such that Darger was considered an “outsider” when this term still meant, “Hold him at arm’s length, please.” By 2002, the year I graduated from art school,

“outsider” was no longer a bad word. Books on Henry Darger could be found in the window of any

Barnes & Noble in town and my own fantasical paintings were receiving admiring attention from curators and dealers. In fact, in 2004, two of my paintings were included in a group show with works by Henry Darger and a number of other contemporary painters who can readily be lumped into the "fairy-tale escapism" camp, including

Inka Essenhigh or the currently red-hot

Dana Schutz.

This shift in art world tastes had little to do with curatorial sensibility. There were simply too many young artists working in this vein for the movers and shakers to ignore the trend. The compulsive, “outsider” approach of Darger had become, long after his obscure death, standard issue gallery fare. Whether or not one would call it a “movement,” as I have heard some people discuss, is irrelevant. It happened and is continuing to gain momentum. The meaning and the value are for time, the critics, and the public, if they ever come back to contemporary art, to determine.

One has to wonder, though, what sort of work we are dealing with. Darger, as I mentioned above, was almost completely solitary. He attended church daily, made his income as a janitor, and returned to a cramped, disaster of an apartment to continue work on his epic Vivian Girls saga and the associated paintings. He never received any artistic training to speak of. This stands in stark contrast to most of the artists on hand at P.S.1. Not only are we dealing with a return to youthful escapism, but the return is a conscious decision, one being made by folks who have Master’s degrees,

iPods, and

Friendster accounts. Would Darger have been eager to discuss the latest EP or hit up the late night bar scene? The main difference between those lost souls like Darger and the average art world fantasist of today is a conscious decision. I decided to work as though I were an advanced child, turning inward and looking for my own little haven via the painting process. Darger just did it; for him there was no asking "What happens if I do it this way?"

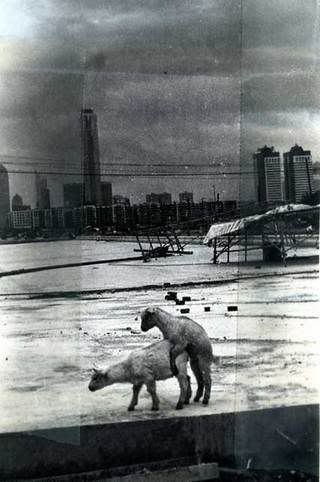

Despite my enjoying much of the work I see at P.S.1 and throughout

Chelsea, I have moved on from such preoccupations in my own studio. Perhaps I felt the room was too crowded with escapists, but most of the decision is a result of my tiring of helplessness. Sure, shit sucks right now, but I don’t feel I can just turn on the rock n’ roll and drift away. I'm excited about my current body of work, even though it has thus far received only lukewarm response; everyone points to the work of two years ago and says, “Now that was really something.” Yes, it was “something” and I still enjoy the paintings, but it ain’t what I’m making now and there are over three thousand other artists, if not many more, weaving similarly self-absorbed fairy-tales out there. Every week, I learn of another terrific young artist working in this vein; I’m rooting for all of them. For my part, though, I’ll head off to my studio and make paintings about the relationship between man and beast, or as some academics call it,

anthrozoology. There aren’t as many rocket ships, dinosaurs, or

indians populating these works, but I’m still smiling, even if no longer blonde.

Photo credit: Painting by Henry Darger, circa 1960s